A friend recently noted that TV post-Breaking Bad seems to be getting more violent. Typically I’d discard this as your run-of-the-mill “kids these days” complaint, but somewhere between grimace-inducing episodes of The Handmaid’s Tale and Fargo, I realized, well, maybe he had a point. Game of Thrones fits the bill. So does HBO’s adaptation of Big Little Lies, which was (I’d say justifiably) darker than its airport-thriller source material. The list goes on.

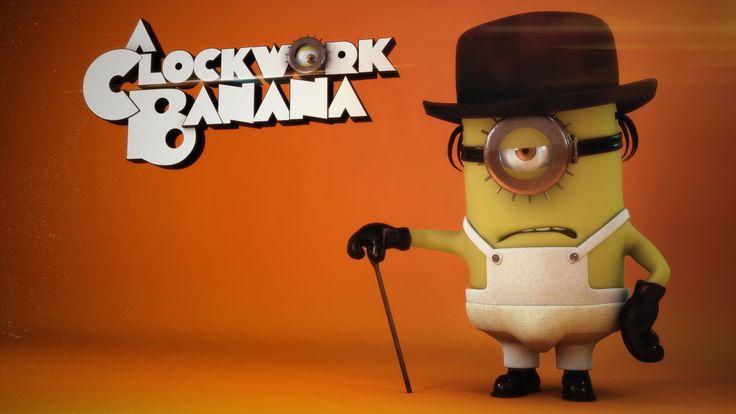

I was reminded, next, of the landmark violence in Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange. For the (lucky?) uninitiated, it tells the story of a violent young man named Alex, who, after being imprisoned for murder, undergoes horrifying aversion therapy.

After his “treatment,” it seems Alex can no longer choose violence: “‘Choice,’ rumbled a deep goloss… ‘He ceases to be a wrongdoer. He ceases to be a creature capable of moral choice…’” When he is released, however, we learn Alex’s taste for violence is insatiable.

The predominant interpretation—and this is how the author himself seems to read it—is that Alex is predisposed to sin. A clockwork, so to speak—a machine. Regardless of the what happened to him during his “treatment,” Alex is so bound in his violence that no government-sanctioned force could cure him.

At least, this is where the first US edition, published in 1962, ends. At the time, the American editors decided it was best to omit the twenty-first chapter, in which Alex grows up and dreams of settling down and having a family—develops, in other words, a preference for the higher moral choice. According to Burgess, the American editors thought this ending was “bland and it showed a Pelagian unwillingness to accept that a human being could be a model of unregenerable evil.”

The American editors, it seems to me, were onto something.

Stanley Kubrick’s disturbing 1971 film (that I’ve never actually finished) adapted the edited version, the story of utter depravity. It was the film that popularized Alex’s final, sarcastic words: “I was cured all right.”

Fifteen years after the book’s release, Burgess wrote an addendum entitled, “A Clockwork Orange Resucked.” (What a wonderful title! No matter what his stance on the human will, you gotta love this guy’s writing.) Burgess implored the world to forget A Clockwork Orange, because its popularized version portrayed humanity as morally imprisoned:

By definition, a human life is endowed with free will. He can use this to choose between good and evil. If he can only perform evil, then he is a clockwork orange—meaning that he has the appearance of an organism lovely with colour and juice but is in fact only a clockwork toy to be wound up by God or the Devil or (since this is increasingly replacing both) the Almighty State. It is as inhuman to be totally good as it is to be totally evil. The important thing is moral choice.

So these are the questions borne by the title: are humans puppets? What percentage good are we, what percentage evil? Is free will—as it is popularly conceived—a given? The American editors dared to think not.

In a chapter from Grace in Practice entitled, “The Four Pillars of a Theology of Grace,” Paul Zahl parries hypothetical claims similar to Burgess’:

Often when the subject of the un-free will comes up, people jump ahead of my claim. They think I am talking about predestination. They think I mean Pavlov and little dogs with bells and shocks. They think I am trying to corner them into some kind of idea that makes people into puppets. To this I say, “You’re ahead of the game. I am talking about one thing, and one thing only: how people actually act and whether they are under compulsion in certain situations. Please don’t talk to me about puppets until you have answered me about addicts.”

Alex is an extreme case, no doubt. Nevertheless humans bend toward undesirable circumstances, often unknowingly. From The Big Book of AA:

We were having trouble with personal relationships, we couldn’t control our emotional natures, we were prey to misery and depression, we couldn’t make a living, we had a feeling of uselessness, we were full of fear, we were unhappy…

Alex is out-of-control, unhappy, probably motivated by fear. Not only is he violent but he is addicted to violence; it is compulsive. That doesn’t make him a puppet, necessarily, dancing from strings held by an invisible man with red horns and pigs’ feet (or a white beard). Yet he is captive to rage and helplessly cruel.

Burgess, who was raised Catholic, laments the reality of “original sin”:

Unfortunately there is so much original sin in us that we find evil rather attractive… Unfortunately my little squib of a book was found attractive to many because it was as odorous as a crateful of bad eggs with the miasmas of original sin.

I agree this is possibly why Kubrick’s shocking film entranced its viewers, and also why, perhaps, violence has become a heavily featured component in much of contemporary media. Even as we are repulsed by it, we recognize its truth, and our vulnerability. It reflects our original sin—our “utter depravity.”

Burgess writes with dismay that we love A Clockwork Orange because we love to see “evil prancing on the page and, up to the very last line, sneering in the face of all the inherited beliefs, Jewish, Christian, Muslim and Holy Roller, about people being able to make themselves better.”

Allow me to gently peel Christianity out of the lump of self-improvement: this particular religion is not about humankind’s ability to improve. It is about the salvation of sinners, and the resurrection from the dead. As Paul Zahl says in Grace in Practice:

Traditional Christian theology, Catholic and Protestant, rooted as it is in the pessimism of Paul and the radical pessimism of Augustine, understands the will as bound, not free. […]

If the will is free, then we do not need someone to save us. We may need a helper, but we do not need a savior. […] The doctrine of the un-free will is a biblical and descriptive approach to everyday life, not the invocation of some overarching puppeteer. We are going to stick to one idea, a single observation: Human beings are not as free to act as they like to think they are. They are more hemmed in, more constrained by outward circumstance and forces within, than they wish to concede…The fact is, we often do what we do not want to do, and do not do what we want to do. I am not the first person to have said this. […]

Think about the obvious case, the obvious prison of the “free” will: addiction. You want to stop drinking. You insist that you can stop drinking. All you need is a little “strength”…If you could just get all little strength you could stop dirnking. But the fact is, you always go back to it…

Take the further example of depression. Depression descends on you like a “wolf on the fold” (Lord Byron). For no “rational” cause at all, you find yourself taken over by sadness. You cannot look anyone in the face; you can barely put one foot in front of the other; the flowers have no smell and the leaves no color. You are a walking dead man…

We can extend the point to any case of fretting or worry. Can you talk yourself out of fretting? Can someone else? People sometimes tell me to relax, especially when they feel a little uneasy with my unceasing activity…If I were able to relax, don’t you think I would? I can’t relax!…If I had “free will,” I would be able to switch from high-intensity to easygoing in a heartbeat. But I cannot. I cannot. (103-107)

Alex, like the addict, or the depressive, or the worrywart, is bound: he is unable to not be violent. This may at first strike us as bad news. (It’s certainly bad news for the good-looking devotchka he plans to carve up with his cut-throat britva.) The bound will does real damage; add to that, it’s also painful to see ourselves as villains, to lift off that protective lid of self-righteousness and see Alex’s savagery in our own impulses; that evil isn’t what we take in but what we put out.

A Clockwork Orange, like so much of the violence we now watch through our fingers, finds us on the wrong side of the line. Somehow we always wind up there, regardless of our efforts to be good (Fargo conveys this especially well). We work like machinery, ticking towards “wrong,” because we are clockwork addicts and clockwork depressives and clockwork cheaters and clockwork self-justifiers. Christianity understands this fundamentally. Yet for every harm, there is redemption. A twenty-first chapter you might say. But it has nothing to do with our will.

There are some clocks that cannot be fixed, but they can be and have been forgiven. It is this forgiveness that redefines who we are: no longer part-clockwork, no longer part-orange but totally, creatively, both.

We are 100% sinners and 100% saints, in accordance with the love that comes from outside of ourselves. It enters our stories of violence and redeems them, so that when we reach the end, we can say without a trace of sarcasm, I once was blind but now I viddy. I was cured all right.

COMMENTS

3 responses to “A Clockwork Theology and the Un-Free Will”

Leave a Reply

This is excellent, CJ!

Excellent article. Solzhenitsyn’s line between good and evil passes through the human heart. As John Newton said, we are blind until we see. It is important to note that Jesus always honored free will. He was never coercive. But he called us to make a choice. Sometimes that choice is to get some help.