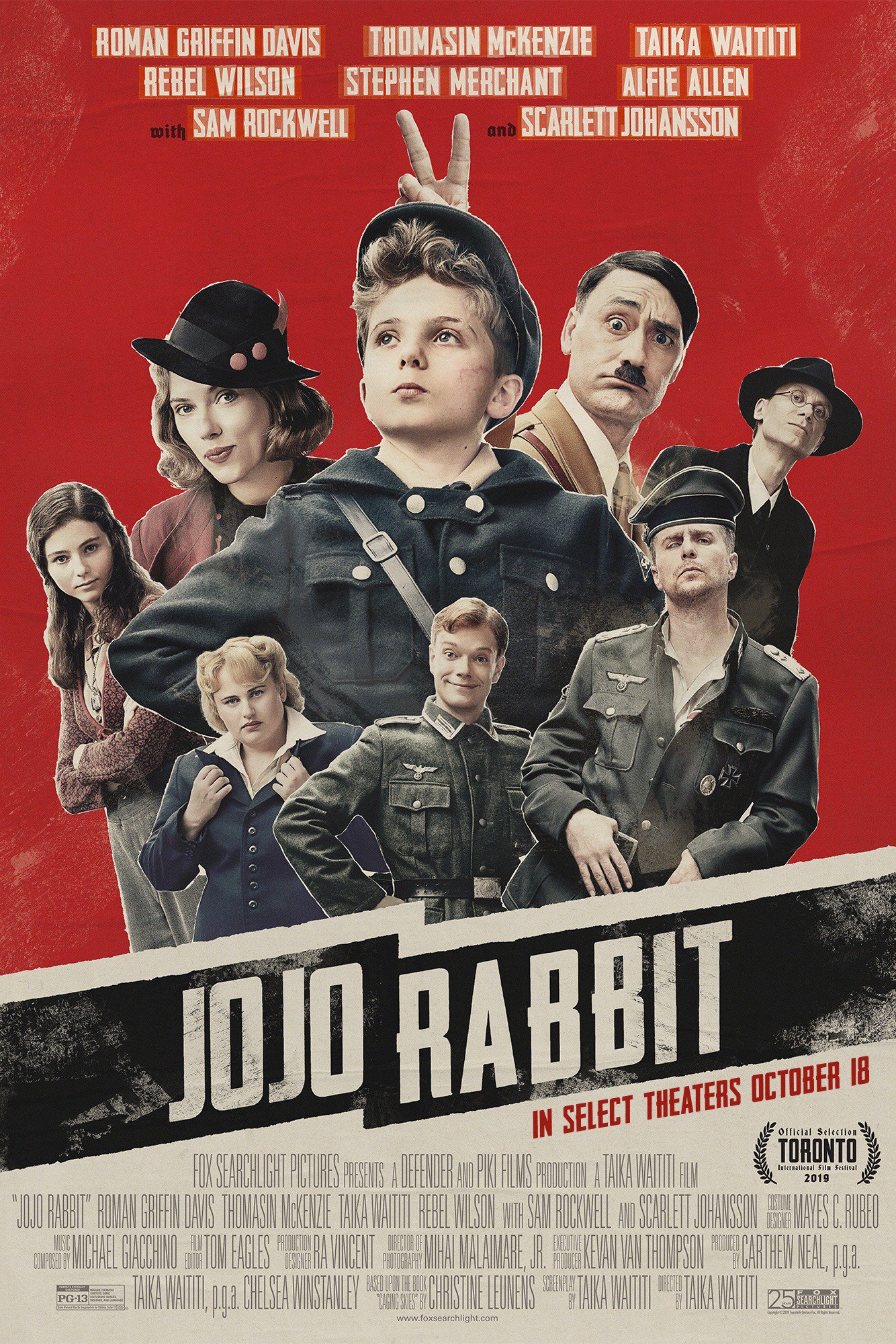

Loud and rambunctious: a couple words that might describe the trailer for Taika Waititi’s satirical new film Jojo Rabbit. We might also add to those: crass, audacious, daring. After the release of Joker a couple weeks prior, the world needed a film that would be a little more light-hearted and encouraging. This is where I thought Jojo Rabbit would come in and save the day, with all of Taika Waititi’s unrestrained humor. Thor: Ragnarok, Hunt For The Wilderpeople, and What We Do In The Shadows are among a few of his other films, all of which should be on your list to watch, if you have not checked them off yet.

Set during the Second World War, Jojo Rabbit follows 10-year-old Johannes Betzler, nicknamed “Jojo,” as he wrestles his way through the Hitler Youth, an organization aimed at indoctrinating children with Nazi ideology. Jojo is accompanied throughout the film by an imaginary friend who appears as a satirical version of Adolf Hitler and is portrayed by Taika Waititi himself.

The film covers a swath of topics including war, violence, racism, childhood, and parenting. With all of its boorish humor and potential insensitivities, Jojo Rabbit is sure to stir up some odd and conflicting emotions. However, what might go unnoticed in the film are some of its quieter moments. Sure, we will “see” them, but what we might miss is how deeply these moments affect Jojo’s heart. (Some spoilers below.)

Early on in the film, we see a conflicted Jojo struggling to muster up any of his so-called Nazi strength to strangle a rabbit as a demonstration of his allegiance to Hitler. This failure earns him, among his peers, an additional nickname, and the title of the film, “Jojo Rabbit.” After running into the forest to lament, his imaginary Hitler psychs him up. Hitler’s cheerleading leads Jojo running back to the camp only to snatch a hand grenade and blow himself up in the process—fortunately not fatal.

This brings us to one of the first quiet moments when his mother, Rosie, comes to the hospital to care for Jojo and take him home. The grenade incident leaves Jojo with a limp and a scar on his face, which he loathes; he believes he is now ugly. After a short period of recovery and help from his spunky, strong-willed mother, Jojo is given a volunteer job at the Hitler Youth office to distribute Nazi propaganda.

Upon returning home one day, Jojo hears some noise upstairs and discovers a Jewish girl hiding in the walls of a room that belonged to his sister. They find themselves in a classic catch-22 when Elsa, the Jewish girl, explains that turning her over to the Gestapo would result in the capture and death of Jojo and his mom.

Later in the film, one of the more significant moments occurs at the dinner table where Jojo displays his angst and anger at his mom. Sipping red wine, Rosie pushes back gently, sharing her beliefs about wanting the war to end and hoping specifically for the Allied powers to win. Jojo continues to fight back by calling his mother names, which only garners a soft roll of the eye from her. She doesn’t believe him for a second! What happens here is significant because it is silent; it goes against our every instinct in what it means to be a parent, a friend, or mentor. We believe (or once believed) that change happens when we successfully combat violent ideologies with better ones. We believe that chastising and punishment will reap the rewards we seek. Rosie does exactly the opposite by letting Jojo be who he thinks he wants to be.

Paul Zahl, in Grace In Practice, has a few things to say about how this particular grace works in relationships:

When you love someone from grace, there is no result for which you are looking. It is one-way love. Grace neither expects anything in return nor “tweaks” the object of its concern. It is not action-consequence love. It hopes all things but expects nothing. Certainly it expects nothing back. It is prayerful, in the extreme, but has no plan for the future. A theology of grace in practice depends on the Holy Spirit of God. The heavy lifting in all human relationships comes from grace, which is block-and-tackle like no other.

What we see Rosie do at the dinner table is largely without expectations. Jojo wants his father, who he believes is fighting for the Nazis. So his mother walks to the fireplace, takes the ashes, and gives herself a fake beard to impersonate Jojo’s father. Think Ash Wednesday but a beard. This catches Jojo off-guard, as grace always does, and begins to soften his heart. Both Rosie and Elsa have said that dancing will be the first thing they do after the war ends, yet here we witness Rosie dancing in the dining room in the midst of a war. She invites Jojo to dance with her. No further words are exchanged as they dance together, silently.

Throughout the film, we are continuously met with scenes that invoke these same themes of grace. What affects Jojo’s heart was not a better ideology nor strict admonishments from his mother. What ultimately initiated and continued to change Jojo was a love that he could never have expected or imagined. He was dearly accepted with every ounce of his ugliness, on the inside as well as the outside. To quote Paul Zahl once more, the “irony is that grace always produces the sterling character that the law intends… grace is not finally against the law because the qualities that grace births in people are the same qualities that the law sought but failed to birth.”

A few weeks earlier, in Todd Phillips’ Joker, we watched a story that lacked any trace of grace and hope; Jojo Rabbit is ripe and sweet to the core with grace and hope. Although wildly satirical about Nazi culture and ideologies, it displays for us a dark reality. The film’s portrayal of racism and hatred are undeniably uncomfortable; Taika Waititi did not hold back. And while Joker and Jojo Rabbit both gave us a grim look into certain evils, only Taika Waititi’s film delivered us from the binds of those evils. If Joker serves as a lecture on Luther’s On The Bondage Of The Will 101, then Jojo Rabbit is a class that aims to show us the grace and hope that frees us in light of our bondage.

The moments of grace in our own lives are often the quietest moments. Ones that were so often missed in all the distractions of life. With gunshots and explosions ringing in our ears, leaving us with lifelong tinnitus, we can miss the little dances that are already happening in our lives, even though our personal wars have yet to cease. These quiet promises of a final dance party are subtle but we would be amiss to underestimate them for one second. True instances of grace seldom leave a person unchanged. As people who are bound to time, we can fall into expecting that the love and grace we dish out should be returned with immediate results. We forget that grace isn’t bound to time. It isn’t worried about the question of “when?” True grace lifts the burden of time and the demand of immediate change. It loves you as you are, just like Jojo’s mother, whose grace often appeared as permission; she knew exactly what loving her child meant. It required a death on her part, and she gladly carried that weight for the sake of her son. She displayed immense patience with every ounce of darkness and hatred in his soul. Dare I say, she was trusting in something bigger and more capable of changing the heart of her child.

If our experience of showing grace isn’t a type of death, it certainly is a risk of personal pain and suffering. Both of which we witness in Jojo Rabbit. Grace is littered throughout the film. For a film that definitely breaks the record in the number of “Heil Hitler” phrases spoken, whispered, and belched, we should notice that grace arguably does its most profound work where war, violence, and hatred serve as the background. In other words, grace is very much present in the darkest shadows of our lives. It doesn’t turn away when wickedness enters. It laughs and embraces and ultimately dances with the person as though they were spotless, donning the most beautiful homecoming dress. And perhaps they really were spotless all along.

COMMENTS

2 responses to “The Quiet Dances and Grace in Jojo Rabbit”

Leave a Reply

Loved the movie, love the piece!! SO happy to see your name on here Bryant.

I just watched this movie and loved it. I enjoyed your column even more. Beautiful writing and much to think about. Yes, grace.