Another excellent reflection from our friend, Tim Peoples.

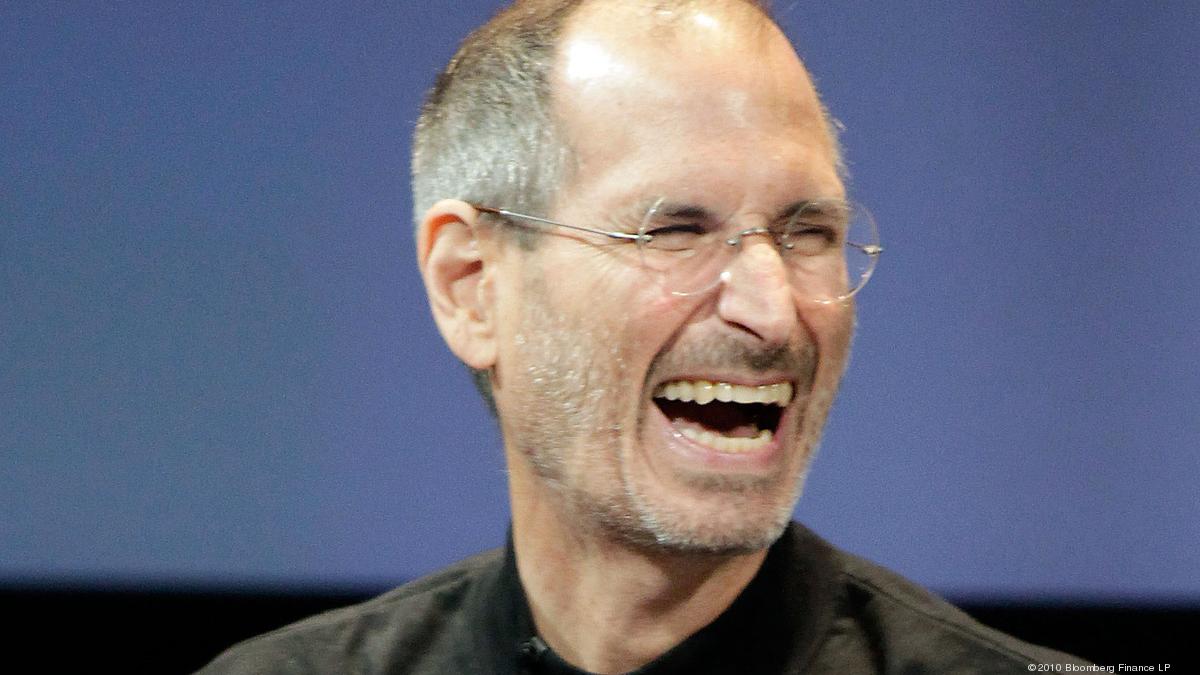

The 2015 release of both a straightforwardly critical documentary and (based on the marketing so far) a celebratory biopic about Steve Jobs may give the impression that he is a polarizing figure, i.e., that Alex Gibney’s Steve Jobs: The Man in the Machine and Boyle + Sorkin via Isaacson’s Steve Jobs represent, respectively, those who dislike and those who love the man. As Gibney shows in the introduction to The Man in the Machine, however, there is no meaningful bifurcation of opinion about Jobs’ legacy. The dominant cultural assumption, which the documentary was explicitly created to undermine, is that Jobs is the great, revolutionary entrepeneur, designer, engineer, inventor, CEO, and visionary of the past 100 years (or more).

You can see this widespread adulation in Gibney’s montage of images and videos mourning Jobs’ death, from flowers at Apple Store entrances to teary vodcasts to Katie Couric’s tribute. We’ll all see it when practically no one remembers Gibney’s documentary but the Boyle/Sorkin/Isaacson film makes hundreds of millions of dollars.

The film uses recorded footage extensively, inviting us to pit our ideas of Jobs against the man himself. The footage supports the film’s subversive thesis and is supported by a foreboding ambiance that makes Jobs’ every facial expression and utterance deeply creepy, childish, arrogant, or manipulative. We see Jobs in his later years complain in sworn testimony that he wasn’t sufficiently appreciated by his board (which justified backdating stock options). We see him reflecting how his and Steve Wozniak’s sale of blue boxes—which Jobs readily admits were illegal—was an essential moment in Apple’s early history.

The rest of Gibney’s film is composed of interviews and archival footage of Jobs’ friends, employees, bosses, and collaborators, many of whom give truly horrible stories of maltreatment and cruelty. A short, incomplete list: Jobs denied the paternity of his first daughter and agreed to pay only $500/month in child support, lied to Wozniak about how much money they were paid for an Atari game (he said $700 and gave $350; they were paid $7000), colluded with other Silicon Valley tech CEOs to keep employees from jumping ship, sorta-kinda named his daughter after his newest computer model (not the other way around, as is assumed), and evaded responsibility for Foxconn working conditions and the attendant suicides. Even Jobs’ eventually fatal cancer had an unethical component; he hid the severity of it for a couple of years, even though he should have disclosed it to shareholders.

The interviews yield some genuinely touching scenes about Jobs, but none are completely positive. Bob Belleville, who was director of engineering at Apple from 1983-1985, lost his marriage and children because of the commitment his job required. Yet you can see the pride he takes in showing the documentarians his signature etched into the inner casing of the Apple II. He tears up while reading an obituary of Jobs that concludes,

What is in that bag of goodies? The iPod, the iPhone, the iPad are so personal. They are warm in your hand. They sing to you when you’re alone. They are caressed. In those three years together, I packed in a decade or two of experience. Steve packed in a couple of centuries in his 56 years. He did everything he wanted, and all on his own terms. It was a life well and fully lived, even if it was a bit expensive for those of us who were close.

I could spend another 1000 words on all the revelations of Jobs’ inner conflicts and outward misanthropy, but that may obscure the larger question that The Man in the Machine seeks to ask: Was the consumer’s relationship with Jobs expensive, or are we the sole conflict-free beneficiaries of Jobs’ life? A segment in a This American Life episode about Apple’s Chinese manufacturing plants has been playing on repeat in my head for the past couple weeks:

Ira Glass: I am the direct beneficiary of those harsh conditions.

Charles Duhigg: You’re not only the direct beneficiary. You are actually one of the reasons why it exists. If you made different choices, if you demanded different conditions, … then those conditions would be different overseas.

This point, which underlies many movements of social justice-motivated consumerism, can be expanded to Jobs’ behavior, both public and private. Is the public complicit in ignoring or even rewarding the coarse style that Gibney so thoroughly documents?

The ubiquity of Apple products, the company’s current status as the world’s most valuable company, and the secular sainthood that Jobs has enjoyed for the last four years is all the proof you need to this question. It makes no sense for me to argue that I am not complicit in propping up the Jobs legacy, because I am typing this on an iPad Air and listening to Pandora on an iPhone. That we (as a culture, as consumers) are complicit, that we admire the visionary CEO who destroyed peoples’ lives—that is not really up for debate.

Our complicity both in unfair labor practices and Jobs’ freedom to act as he wished (and not as he ought) is the primary way that our relationship with Jobs has proven expensive. Speaking for myself, I extend that complicity daily, spending too much time using devices for little or no benefit to myself, my family, or my community. I am a supporter both of fair labor and quality family time. Therefore, my hypocrisy stings when I see “Made in China” etched on an Apple device or I realize that I’ve been inattentive to my children for the last 10 minutes because I was staring at one. The price of our adoration of Jobs, therefore, is isolation from social awareness and the people around us.

Gibney brings this hypocrisy to the viewer in last few minutes of The Man in the Machine. If we trust Gibney’s data, then we cannot hold the rosy view of Jobs we have deluded ourselves with over the last few years. Gibney recently summarized his own take on Jobs, which The Man in the Machine eloquently supports:

For all the criticism of Jobs, there is also a greatness to the man… He could be charming and charismatic. And his ability to make us comfortable with technology became, over time, like shared folk wisdom.

But his legendary cruelty was not essential to what he accomplished. It became something that everyone was willing to overlook because his company made such beautiful products which made shareholders so much money.

Jobs did not need to be cruel, but he chose to be; we did not need to reward him with our dollars, but we chose to. Steve Jobs: The Man in the Machine shows us, because we desperately need to be reminded, that all our good guys are bad guys. Lest the viewers judge too harshly, though, the film’s implicit concluding argument is, essentially, that we are all bad guys—not just Steve Jobs, but also Steve Wozniak, Bob Belleville, you, and me—because we tolerate and even admire such outward cruelty. The screen of an iPhone dims after 30 seconds, but, thank God, grace shines the light of forgiveness when we are alone in the darkness we allow and the darkness we create.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply