If I need another reminder of my overwhelming guilt and shame, I can always turn to the movies. It’s perverse, but I definitely derive some libidinal satisfaction in recognizing guilt on screen. Over the years we’ve seen various heroes or, more appropriately, antiheroes of this ilk. Martin Scorsese’s develop ed an impressive oeuvre on the subject. Manchester by the Sea overtly depicted a man dealing with it. You don’t have to look far. Movies like this do well to highlight the fact that we mess up. The gap between who we aspire to be and who we really are is significant. As Junot Diaz said in a recent lecture, espousing an impressively low anthropology, “There is no such thing as a good guy.” I resonate with what that says about my sinful heart, but I’m squeamish about its implications for my favorite fictional characters. Shouldn’t we want to see a good person modeled at the movies? A great film can drag us through the muck while also highlighting beauty and elevating the mind, but clinging to mistakes and regrets stymies expression. After all, that’s what Christ died to free us from.

ed an impressive oeuvre on the subject. Manchester by the Sea overtly depicted a man dealing with it. You don’t have to look far. Movies like this do well to highlight the fact that we mess up. The gap between who we aspire to be and who we really are is significant. As Junot Diaz said in a recent lecture, espousing an impressively low anthropology, “There is no such thing as a good guy.” I resonate with what that says about my sinful heart, but I’m squeamish about its implications for my favorite fictional characters. Shouldn’t we want to see a good person modeled at the movies? A great film can drag us through the muck while also highlighting beauty and elevating the mind, but clinging to mistakes and regrets stymies expression. After all, that’s what Christ died to free us from.

Mike Mills’ 20th Century Women fits interestingly in this conversation. A stylish, thoughtful movie, Mills frames it in reaction to the camera friendly dynamic of male glorification that spawns much of our cinematic fare – even if the protagonists are made to suffer or look pathetic they often do so on the backs of others and return more beautiful than ever to conquer their enemies. Like other mbird favorites (Noah Baumbach, Whit Stillman, Wes Anderson, Woody Allen), you can tell Mills is a sensitive guy – and naturally that’s appealing to sensitive guys, myself included. But it’s wrong to equate sensitive with good.

Mills risks falling into the trap of constructing a realistic and sympathetic male character. His guilt leads him to spend too much time apologizing for himself. Mills draws from his own experience being raised by a single mother to tell the story of a teenage boy named Jamie. Growing up in Santa Barbara in 1979, he lives with Annette Bening’s Dorothea and the tenants she keeps in her home. A delightful Greta Gerwig and a bohemian Billy Crudup pay rent and Elle Fanning often spends the night in order to avoid her own overbearing parents. Early in the action, Bening sits Gerwig and Fanning down and officially enlists them in helping her raise Jamie to be a ‘good’ man. Don’t you need another man to do that? They parry. No, Bening insists, We can do it.

So Greta Gerwig good-naturedly gives him some books on the women’s movement – and the importance of the clitoris. Elle Fanning shows Jamie how to look cool smoking a cigarette and confronts him honestly when he gets piggish around her. These are both touching attempts to impart wisdom. But when Jamie tries to apply them in conversation with his friends, he ends up with a black eye. His right-handed power is overwhelmed by stronger right-handed power, no surprise there. Jamie models masculinity best, though, when he goes off the ‘good guy’ script. He accompanies Gerwig to get the results of a cancer screening and stands by Fanning when a relationship cracks up. These episodes aren’t about Jamie, but, unlike his father, he shows up. He’s there.

So Greta Gerwig good-naturedly gives him some books on the women’s movement – and the importance of the clitoris. Elle Fanning shows Jamie how to look cool smoking a cigarette and confronts him honestly when he gets piggish around her. These are both touching attempts to impart wisdom. But when Jamie tries to apply them in conversation with his friends, he ends up with a black eye. His right-handed power is overwhelmed by stronger right-handed power, no surprise there. Jamie models masculinity best, though, when he goes off the ‘good guy’ script. He accompanies Gerwig to get the results of a cancer screening and stands by Fanning when a relationship cracks up. These episodes aren’t about Jamie, but, unlike his father, he shows up. He’s there.

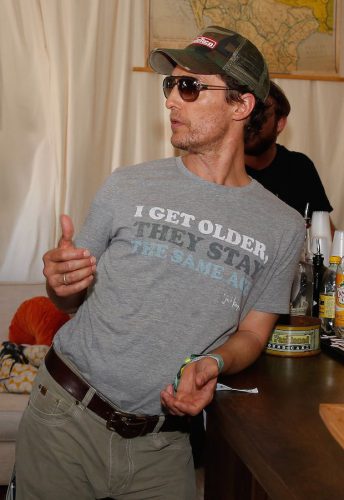

The other guy in the movie is Billy Crudup, a gentle-souled hippie, who’s shot sympathetically and seems harmless enough to a male viewer. At his core, though, he’s a McConaughey-esque charmer. There’s no there there. After he throws his physicality around in front of Gerwig and Bening, his landlord calls him out. True to his bohemian ethos, he responds, “It’s not serious.” In a cutting rejoinder seemingly directed against an entire generation, Bening says, “If it’s not serious, then why do it?”

We don’t get to see what kind of man Jamie grows up to be, but we hope that the love shown to him by Bening and the other Twentieth century women might help him become good.

One critic called Mills’ tackling of the issue of raising a good man evidence of the filmmaker’s “saccharine self-satisfaction at his own sensitivity.” Whether I agree with that particularly harsh critique or not – although I do admire the alliteration – the point is clear: mirror your soul in a character, however sensitive he/she is, and you will come up with a cloudy, sordid image, colored in by guilt and shame. Thank god, then, that we’re provided with righteousness outside of ourselves. It’s helpful here to return to Diaz’ bold aphorism. “There’s no such thing as a good guy,” and any attempt to set out such a figure is doomed from the start. Sure, it’s a fun thought experiment to weigh different models of masculinity, but none of them come close to Christ, and look what we did to him.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7SyZZi0D18M

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply