This essay comes to us from Taylor Mertins:

Jesus, full of the Holy Spirit, returned from the Jordan and was led by the Spirit in the wilderness, where for forty days he was tempted by the devil. He ate nothing at all during those days, and when they were over, he was famished. (Luke 4:1-2)

His hair was still wet from the baptism in the Jordan River when Jesus was led into the wilderness by the Spirit. Mark tells us that the Spirit literally kicked Jesus out in the unknown places.

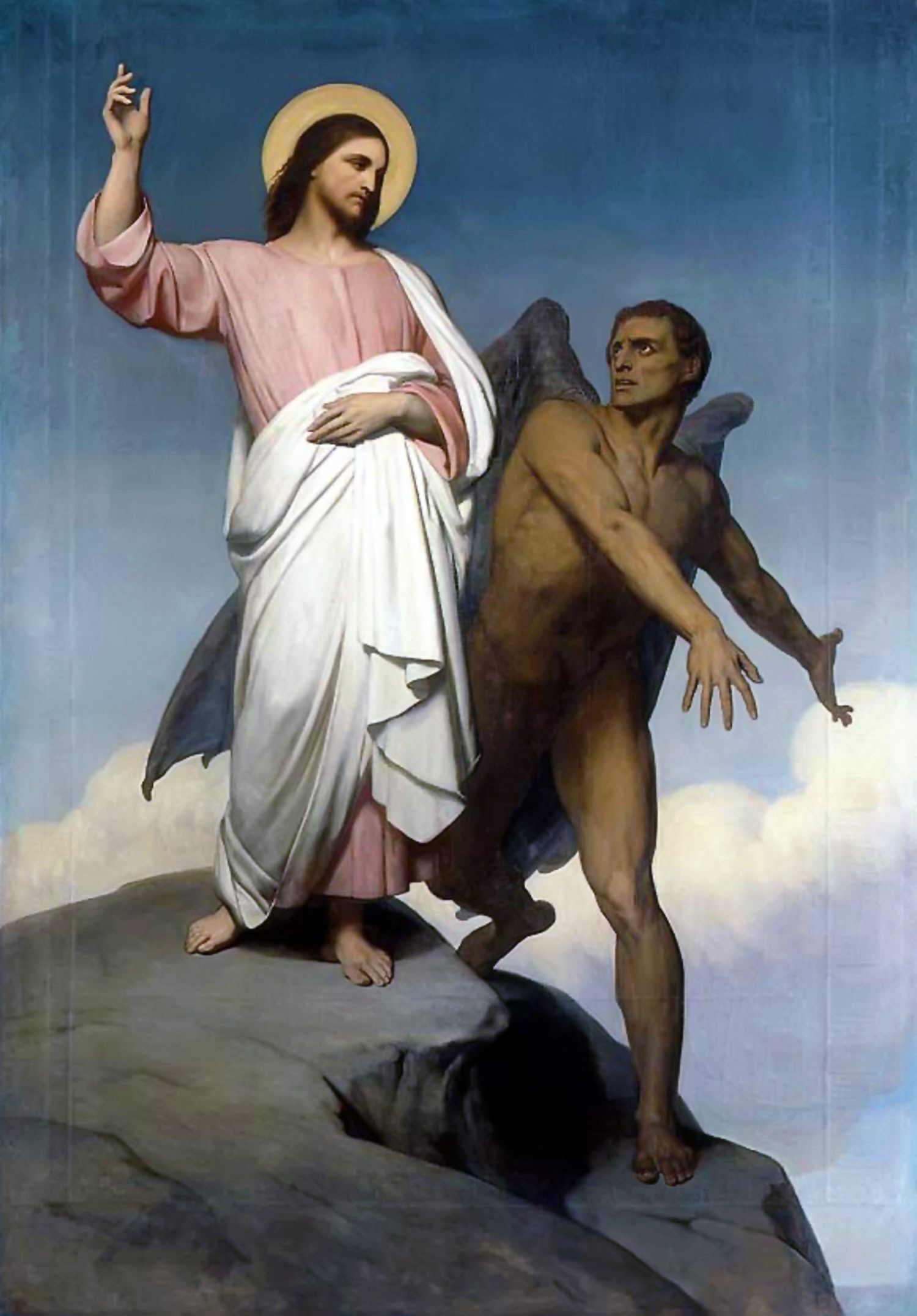

And there, for forty days, Jesus ate nothing and was tempted by the devil.

It is a tradition in the life of the church to begin the forty days of Lent by reading about Jesus’ forty days in the wilderness. We, in a sense, mirror the journey Jesus faced with our own attempts at wrestling with temptation while fasting from certain items, behaviors, or practices. Some of us give up social media, or chocolate, or unkind thoughts (good luck with that one), while some of us add new disciplines like daily Bible reading and prayer, intentional silence, or journaling.

Nevertheless, this temptation story leaves us with a question: Who in the world is this Jesus?

Earlier in the Gospel we read about how he was born to a virgin in a back alley of the Town of Bread, and how an angelic host sang the Good News of his arrival to a bunch of nobodies out in a field in the middle of the night. Later, magi from faraway places brought him gifts fit for royalty, and King Herod was so terrified of his arrival that he ordered all of the children in Bethlehem to be put to death. We then fast forward to his baptism by his cousin, after which the sky was torn into pieces as a voice bellowed, “This is my Son, the Beloved, with him I am well pleased.”

But now this Son of Man and Son of God is out who-knows-where dealing with who-knows-what. And yet, this story tells us exactly what kind of Messiah this Jesus is and will be. It gives a glimpse behind the curtain of the cosmos. It helps us to know how it ends just as it begins.

“Okay,” Satan says, “If you are who you say you are, let’s see some ID. No pockets in your robe? Fine. I’m sure you’re hungry. We’ve been out here for forty days. So why don’t you make some of these stones into bread? It might come in handy down the road. What could be more holy than having mercy on the hungry and filling their bellies?”

“It is written,” Jesus says, “That we cannot and shall not live by bread alone.”

“So you know your scripture!” the devil replies, “I understand. And, frankly, I’m with you, Jesus — you can’t just give hungry people food for nothing. They’ll become dependent. No handouts in the Kingdom of God! But what about this? Would you like some political power? Here’s the deal: I’ll give you the keys to the kingdoms here on earth, and all you have to do — it’s a tiny thing really — is bow down and worship me.”

“It is written,” Jesus says, “we shall only worship one God.”

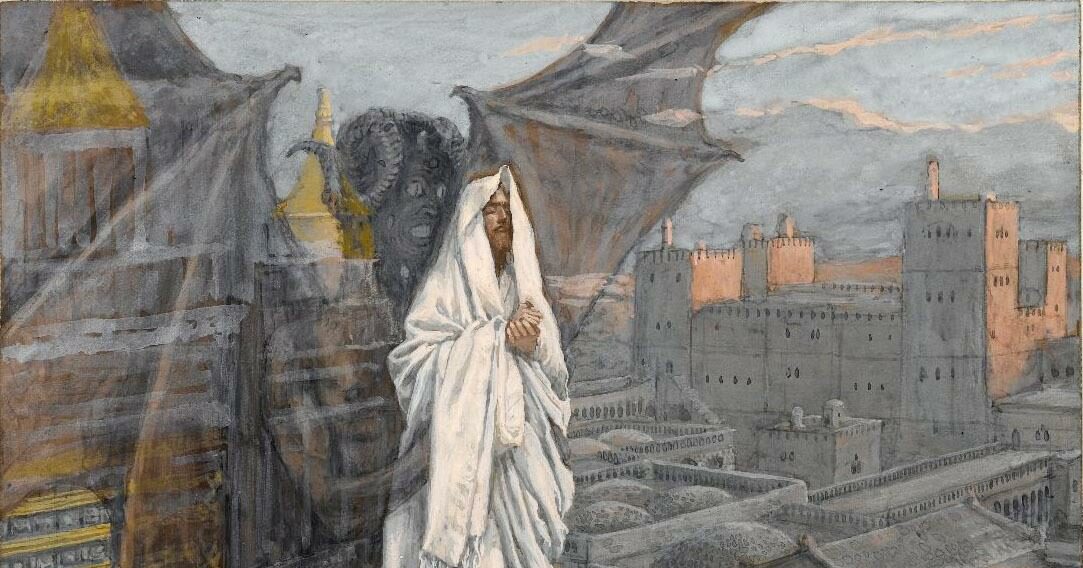

“Okay, okay, geez. Don’t be such a stick in the mud,” the devil continues. “So you won’t show compassion to the hungry, not even yourself, and you won’t just go ahead and make the world a better place through political machinations. Fine. For what it’s worth, I can play the scripture game, too. So what about this? Why don’t you leap from the top of the temple, give the people a sign of God’s power and might. Doesn’t it say in the Psalms, ‘For he will command his angels concerning you to guard you in all your ways. On their hands they will bear you up, so that you will not dash your foot against a stone’? Do it and the people will be filled with faith.”

“It is written,” Jesus says, “that you shall not put the Lord your God to the test.”

“This is getting boring,” Satan intones, “I’m getting out of here.”

Pretty wild stuff. The devil temps the Lord of lords and fails to catch him. The devil even attempts to use scripture to catch Jesus in the snare, but it doesn’t work.

Now, usually, when we hear this story at the beginning of Lent (if we hear it at all), it is framed in such a way to encourage us to resist our own temptations. Lent, after all, is a season when we ditch a bad habit or pick up new ones. And, yes, we should resist temptation; there are things we want to do that we shouldn’t do.

But if that’s all the story is meant to do, then surely Jesus could’ve been a little clearer about what is and isn’t permissible. If Jesus’ temptations are really about our temptations, then wouldn’t it have been better for the Lord to add a little exhortative proclamation for the people in the back? Do you see? This isn’t, really, a story about how we deal with our temptations. It’s actually a story about how Jesus deals with the world, how Jesus deals with us.

Notice, the devil offers Jesus objectively good things: bread, political power, miracles. And yet Jesus refuses all three.

It would be one thing if Satan were to offer Jesus ten Big Macs, or nuclear weapons, or — let your imagination run wild. But the devil doesn’t. Instead, the devil presents Jesus with possibilities for the transformation of the world, and Jesus does nothing.

Except, and here’s the real kicker, throughout the rest of the Gospel, Jesus does, in fact, do all the things that the devil suggests!

Instead of whipping together a nice loaf of artisan bread out in the wilderness, instead of making some biscuits from the rocks, Jesus later feeds the 5,000 with nothing more than a few slices of wonder bread and a handful of fish sticks. Instead of getting caught up in all the political policies to Make Jerusalem Great Again, Jesus reigns from — of all places — the cross of his execution and then ascends to the right hand of the Father as King of kings and Lord of lords.

Instead of pulling off a Houdini-esque magic trick that would make even the crowds in Las Vegas jump to their feet, instead of jumping to certain death only to be rescued by the heavenly host at the last second, he dies and refuses to stay dead.

We often think of Jesus and the devil as these two far ends of the spectrum, one good and the other evil. And yet, at least according to this story in the strange new world of the Bible, the difference between Jesus and the devil is not in the temptations themselves, but in the way the desired objects come to fruition.

And the devil actually has some good suggestions for the Messiah. Why starve yourself when you can easily rustle up some grub? Why let these fools destroy themselves when you can take control of everything? Why let the world struggle with doubt when you can prove you are entirely worthy of their faith? The devil here, frighteningly, actually sounds a whole lot like, well, us. His ideas are some that we regularly champion both inside and outside the church.

Who among us wouldn’t want to give food to the hungry? Who among us wouldn’t like to see our politics get in order? Who among us wouldn’t enjoy seeing a powerful demonstration of God’s power every once in a while?

But Jesus, for as much as he is like us, is also completely unlike us. For, in his non-answer answers, he declares to the devil, and to all of us, that power, whether it’s over creation, politics, or miracles, doesn’t actually transform the cosmos. Jesus, in his refusal to take the devil’s offers, reminds us that we, humans, are obsessed with believing that power (and more of it) will make the kingdom come here on earth.

And we’ve been obsessed with it since the beginning.

In the early days of the church’s bed-fellowship with the powers and principalities, there were forced baptisms in order to make perfect little citizens.

In the middle ages, the church required more and more of the resources of God’s people in order to get their loved ones out of purgatory, all while cathedrals and clerical waistlines expanded.

And even recently, the lust for power (political, theological, geographical) has led to violence, familial strife, and ecclesial schisms. We’ve convinced ourselves, over and over again, that if we just had a little more control, if we just won one more fight, if we could just get everyone to be exactly like us that everything would turn out for the best. But it never does. Instead, the poor keep getting poorer, and the rich keep getting richer. Marriages keep falling apart. Children keep falling asleep hungry. Churches keep fracturing. Communities keep collapsing.

Therefore, though it pains us to admit it, Jesus seems to have a point in his squabble with the adversary. Because the demonic systems of power, even those under the auspices of making the world a better place, often lead to just as much misery, if not more.

The devil wants to give Jesus a shortcut to ends that Jesus will, inevitably, bring about in his own life, death, and resurrection. The devil wants Jesus to do what we want Jesus to do. Or, perhaps better put: The devil wants Jesus to do what we want to do.

But here’s the Good News, the really Good News: Jesus is able to resist temptations that we would not, could not, and frankly do not. Even at the very end, when Jesus’ hands are nailed to the cross, he is still tempted by the adversary through the voices in the crowd: “If you really are who you say you are, save yourself!”

But at the end, Jesus doesn’t respond with passages of scripture. He doesn’t offer a litany of things to do or things to avoid. Instead, he dies. Instead of saving himself, Jesus saves us. Amen.

COMMENTS

One response to “The Devil We Know”

Leave a Reply

Brilliantly scrupulous analysis!