The 21st century has been a time of revelation. The buried reality of abuse is now being unearthed in our culture and through our laws. Child abuse by the Boy Scouts or any number of church organizations is increasingly acknowledged as the hideous outrage it is. #MeToo has exploded the wall of acceptance of disgusting behavior to the point where its perpetrators are becoming seen as the freaks they are.

But as a baby boomer, I have seen a similar unveiling. Until Janet Woititz wrote Adult Children of Alcoholics (a group coined ACOA) in 1983, drinking was seen as devastating to the drinker, and their loved ones were expected to cope. Then Woititz offered up a startlingly obvious argument. Extreme parental behaviors affect young children all the way into and through adulthood. Post-World War II, alcoholism was just part of life, often tacitly accepted as normal, even socially positive behavior. So it’s not surprising that Woititz’s argument was not explosive until later, when we boomers began to understand what our parents’ lives meant to us. With 100 million boomers having grown up in the ethanol-infused mid-century, the market found the book, and by 1986 it was on the New York Times bestseller list.

When I opened my office in 1987, my landlord referred me to a cleaning lady. She was in her mid-20s, seemed a little sad around the eyes, and was a Wesleyan graduate. Being WASP, I did not pursue why a Wesleyan grad was cleaning offices. But we talked one Sunday afternoon as we toiled in the office alone.

When I opened my office in 1987, my landlord referred me to a cleaning lady. She was in her mid-20s, seemed a little sad around the eyes, and was a Wesleyan graduate. Being WASP, I did not pursue why a Wesleyan grad was cleaning offices. But we talked one Sunday afternoon as we toiled in the office alone.

I have no idea how it came up, but I noted my father was a very high-functioning alcoholic. She nodded and said, “So were my parents.” We stared at each other for a couple of seconds, and we both went back to work.

A week later, the Monday after the next cleaning, Woititz’s book was on my desk, with a cassette of an electronic version of Pachelbel’s Canon. I had seen a synopsis of it in Time magazine, but holding the book, and hearing the odd tones of mechanically rendered heartbreak on the office stereo, I silently cracked. My staff then arrived, and we went to work.

Like my dad, who came off the 6:20 train from Manhattan and drank twelve ounces of scotch from 6:30pm to 7:30pm every day from the moment I knew him, I am high-functioning, just without the drinking. Just with the damage it caused.

Also like my parents, my wife and I delayed the prime directive of parenthood until our mid-30s to serve our higher functioning. We had two healthy boys within 26 months. They were, as all babies are, perfect vessels waiting to be filled. Devotion to protecting their complete vulnerability from any threat, real or imagined, set my late-30s’ brain reeling.

Normally the parents of new parents are the gateway to perspective. But our parents were either dead, due to their mid-century habits, or not very good sources of how to raise children given how they raised us. So I encountered two abiding conundrums: one, a cliche: “You are only as happy as your least happy child.” I realized this when our sons experienced the inevitable vicissitudes of being in their 20s. The second, harder to accept at 64, is that I am only as happy as my childhood allows me to be.

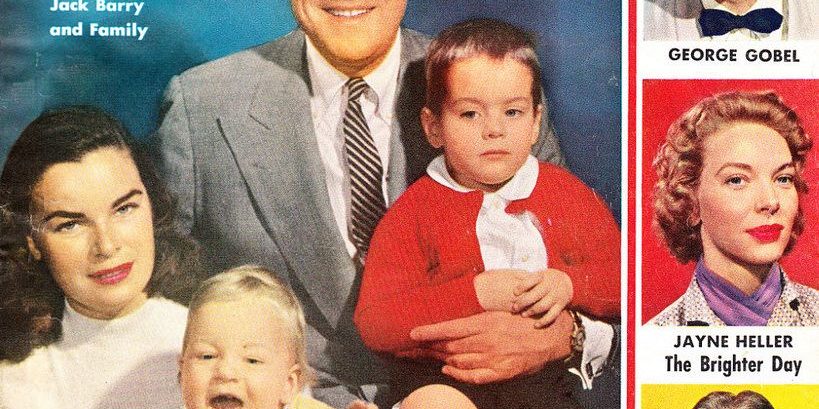

That childhood has become a meme. If you have watched Mad Men you know the Greatest Generation was good at three things: saving the world, making babies, and drinking. Their largest product, the Baby Boom, grew up to feel that they were the hope of the world’s saviors: we boomers all had the empowerment of our parents’ triumphs over the Depression and Hitler with none of the survivor guilt.

The boomer combination of narcissism and dysfunctional upbringings created a huge groundswell of self-imbued redemption boondoggles. We saved the world, too, but from sexism, homophobia, racism, and limitations on lust. Oh, and Nixon.

But the “Me Generation” — “finding ourselves,” whether in yurts, MBAs, or transcendental meditation — faced some hard-edged realities beyond the obvious narcissism. Many of us have largely abandoned any sense of a Higher Power, other than ourselves. For more and more of my ilk, religion is either dispensed with or lip-serviced, especially here in the Northeast.

I am not alone. Lots of babies born in a wash of mid-century PTSD-distracting alcohol have experienced its consequences. Millions like me found themselves in circumstances both intimate and terrifying. The hard-and-fast sanctity of marriage and cast-in-place societal roles and protocols meant each family was its own country, sovereign and exclusive. The ravages of Greatest Generation near-WWII-death made perspectives beyond the trials of war and deprivation complicated.

The stage for this explosion of alcohol was well-set before World War II. When the moral imposition of Prohibition simply failed due to its own impossible overreach, the entire country was flooded with an emotional solvent — booze — at the height of the Depression.

Drinking in the wake of Prohibition’s Epic Fail had no limitations — no seat belts, no surgeon general’s warnings, no sense that children were anything but “resilient.” I know this because my family had three “resilient” children, and a very successful father, and an enabling mother.

Drinking in the wake of Prohibition’s Epic Fail had no limitations — no seat belts, no surgeon general’s warnings, no sense that children were anything but “resilient.” I know this because my family had three “resilient” children, and a very successful father, and an enabling mother.

He was not a happy drunk. His early life was not easy, and its impacts were never examined enough; he never had enough perspective to modify the anger that he showed to anyone he felt deserved it — after the 6:20 train. Being the youngest, I saw my other siblings reduced to “failures” in raw, loud verbal assaults; my mother received verbal assaults far worse — coming at her as loud as a human voice could — usually after we went to bed. My wife had a similarly conditioned childhood.

So after the birth of our second son, with a fully running about two-year-old, my mind flashed on Woititz’s most essential truth, that children of alcoholics “guess at what normal is.” Like all those ACOAs in Woititz’s book, each gift, each blessed event, each act of grace was received by someone who clearly had earned none of it, and in fact did not deserve any of it. And nothing achieved was much beyond forestalling the discovery of my own very failed state (as defined by my parents’ alcohol-galvanized judgment). Part of me will always be living in an alcoholic family.

I know part of me will always be six. You are only as happy as your unhappiest childhood, but you can nevertheless learn that you are loved. You might not feel lovable, ever, but love is as real as the night terrors I have most every time I sleep. I know, upon awakening, that any love I have is God’s grace, and that I have nothing to do with it: and that’s probably why I can, mostly, accept it.

I will never understand my parents much beyond the truth that they were God’s children, just as I am. No better, and no worse. But the damage is abiding, more than twenty years after both of my parents have died. But God is beyond abiding. His presence is the gravity and breath in every aspect of everything that I perceive. It is not a choice. Though damaged from birth, there has never been a barrier between my life and the truth of God in my survival — unmerited, unearned, undeserved, but real.

I wish that love could cure, but not yet.

COMMENTS

13 responses to “I Am Only as Happy as My Childhood Allows Me to Be”

Leave a Reply

Amen.

“I wish that love could cure, but not yet.”

Lovely — thank you.

Yes. And amen.

Mockingbird. Where truth is spoken. Thank you Duo.

This is so incredible, Duo. So grateful for your self-awareness and your willingness to share it.

back atchya

Duo is truly…The Quiet Storm!

love to you

I am still fighting the battles of a generation skipped. Thank you, duo.

My experience is different, the PTSD is real. Yes, I’ve been described by others as exhibiting characteristics of an adult child of alcoholics..BUT our home was very nearly DRY. As I sort it all out, our dysfunction(s) had roots in my father’s very traumatic combat experience in WWII, which left him profoundly changed from the happy-go-lucky guy that my mother knew and married. He was angry; he usually restrained his tendency to physical violence but not always. He spoke to me as little as possible; in the 20 years that I lived in that home, I can recall NO conversation–just orders. No talking about life. I learned to become invisible and to keep myself to myself. My mother reinforced all of this, coping with her own childhood PTSD. The so-called Greatest Generation did “triumph” over depression and war; the ones I knew never let my generation forget that and it was a touchpoint for dismissiveness of any problems encountered by me or my siblings.

I am not without gratitude to these parents who worked very hard to keep roof and bread and clothes available; they did the best they could and I appreciate that and admire their effort. If they had had supportive counseling available, maybe things would have been better for all of us.