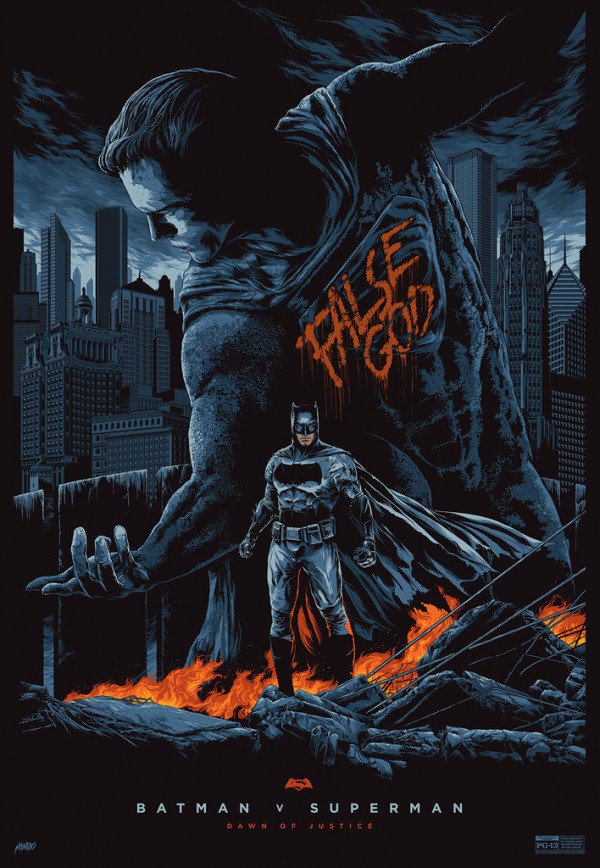

From our comic book expert, Wenatchee the Hatchet, here is a critical take on the recent blockbuster, Batman v Superman.

Prelude to Two Problems

As the “dawn” of the DC cinematic franchise, Batman v Superman falls apart at what I would call the level of mythos. This film had the dual task of continuing the story of Henry Cavill’s Superman from Man of Steel while introducing a new Batman. But the failure of the film is in its invocation of the images, iconography and concepts of two different canons: the Judeo-Christian canon, and the canon of DC comics. It might be expected that the film would fail to effectively invoke God and the devil from the Judeo-Christian canon, but what was unexpected was the failure to effectively invoke the DC canon that inspired the film. We’ll look at these failures in reverse order.

Let’s start with the problems in the title: We have to introduce Batman to Superman and vice versa in a way that leads them to fight rather than cooperate–but the subtitle “Dawn of Justice” signals in advance that by movie’s end they’ll work together. When the spoiler is built into the subtitle, it can hardly build suspense, and so we come quickly to the problem of why on earth these two heroes would fight to begin with. We know of course that there is an iconic fight between the two heroes in a Frank Miller comic (The Dark Knight Returns), but this film insisted on shoe-horning that fight from the DC comics canon without seeming to be all that concerned with precisely how it got us there.

1. Of tights and fights put on for show

But the super-bro show-down isn’t the only iconic moment cribbed from DC comics in the film. Trailers gave away the appearance of a really big Gollum-looking Doomsday (for comic fans, this film was spoiled entirely before the thing ever hit theaters). A Zack Snyder film wasn’t going to feature a Superman who, like in the cartoon Justice League, used his heat vision to lobotomize Doomsday quickly without having to throw a punch–nope, we had to have more city-leveling brawls. But that’s not really the core of the problem in the handling of the DC canon.

This film is supposed to kick off Justice League as a live action saga, and it does so by mashing up two of the most iconic deaths in DC comics history: the death of Superman at the hands of Doomsay and the death of Bruce Wayne in battle with the Man of Steel. This second death is the one that has figured least in even bad reviews of the film, so it’s worth discussing at some length.

Film critics who aren’t DC fans may have recognized this Snyder film was a bit of a turkey without entirely knowing why. A lot of them may not have even realized the titular showdown between Batman and Superman from Frank Miller’s landmark comic ended with Bruce Wayne’s death.

Now those of you who read the comic know, of course, that the death was faked and the reasons for that death are more core to the original tale than is often acknowledged. In the comic, an aging Bruce Wayne returns to fighting crime as Batman, but his style of crime-fighting is seen as a liability in Miller’s version of Reagan-era America. Superman, on the other hand, has become the Reagan administration’s docile lapdog, fighting to prevent foolhardy hardball policies from bringing the United States into nuclear catastrophe. Superman, in the end, is dispatched to take down Batman. Batman decides to battle Superman and to die a glorious death in the process. He plans to make sure to demonstrate he “can” defeat Superman, but ultimately Batman knows he can’t win and even knows that, all things considered, Superman doesn’t even really want to fight him, but the U.S. government isn’t giving him a choice. In Miller’s wry throw-down the two superheroes both know this fight is for show, for other people who don’t have the nerve to fight their own battles. It doesn’t mean they don’t have real differences, but it was not a battle Batman planned to win “for real”—and there was no plan to kill Superman at all.

Bruce Wayne meticulously planned the moment of his death. He rebukes Clark Kent for saying “yes” to anyone with a badge, for mistakenly assuming that anyone with formal power must automatically be good. Clark finds the fight idiotic. Bruce is bone and meat like everyone else–he has to know he can’t win. But Bruce sees that he has become a political liability and believes that Superman has become a joke. Batman believes that America has turned into a cynical self-serving society that isn’t worthy of either of its ideals.

Batman “dies” of heart failure after showing Superman that, if he really wanted to, he could have killed him. This was the glorious death Batman had wanted. Besides, if Batman didn’t die of heart failure, and if Superman wouldn’t kill him, the U.S. government would.

At Wayne’s funeral, Superman hears the renewed beating of Bruce Wayne’s heart. Wayne had used drugs to stop his own heart and revive it, and only the superheroes know. At the service, Clark glances at Wayne’s protégé, Carrie Kelly, smiles, and gives her a wink. In the end, both Batman and Superman knew that the whole thing was just for show. What permeates Miller’s class comic book is this wry sense of detachment from heroes who know they’re being forced into a fight for no particularly good reason–and it’s the last thing you’ll find in Zack Snyder’s film. The second you try to play that iconic fight as if either Batman or Superman “means it,” you’re setting yourself up for failure.

Even if we set aside Snyder’s mistreatment of Bruce Wayne’s death, there’s this other problem with the film: Superman’s death in battle with Doomsday. The fight between Batman and Superman was forced by the scheming of Lex Luthor, and when he discovers that the two guys with mothers named Martha bond surprisingly quickly after just a few minutes of fighting, Luthor switches to Plan B, Doomsday. Hijacking Kryptonian technology, Luthor makes a Frankenstein’s monster of the corpse of General Zod, who was slain by Superman in Man of Steel.

But it is never entirely clear why this Lex Luthor hates Superman beyond the comics’ canon requirement. With just about any other version of Lex Luthor, from Gene Hackman’s take, through Clancy Brown’s take, to Michael Rosenbaum’s take, we got versions of the character in which Luthor’s animosity made sense. Luthor is to Superman what the Joker is to Batman, because Superman represents what we want America to be while Luthor represents what America too often is. Superman could be challenged not by brute force but by tests of his moral compass.

But this rich mine of thematic possibility, which was the basis for Superman: The Animated Series and its follow-up series, Justice League, is consistently abandoned in favor of an incoherent and incompetent invocation of religious themes. Where in the comics Superman died in a brutal fight with Doomsday, here Superman dies because of exposure to Kryptonite. Snyder gives Superman a surprisingly cheap Christ-like sacrificial death that, within the rules of his character, shouldn’t even be possible. (If green Kryptonite takes away his powers and weakens him to the point of death, how is Superman able to fly wielding a Kryptonite spear to impale Doomsday?)

So Snyder’s film ends with Superman’s death while the audience awaits his inevitable resurrection before we’ve even gotten to the second official Superman movie. Save some of that for the sequel! Or not. This could be why it feels as though when “everything is at stake” nothing is at stake.

Roger Ebert complained that in Superman films the problem is that it always comes back to Kryptonite—it seems nobody telling a Superman story can think of any other way to challenge him. The truth is that Kryptonite hasn’t stopped Superman from wielding Kryptonite spears (Batman v Superman) or lifting an island made of Kryptonite (Superman Returns). For being Superman’s most famous weakness, the live-action films have been blissfully unconcerned with treating that weakness like a weakness as long as a big, emotional “moment” can happen. Writing for that moment, while forsaking all the most basic “rules” of your character and the character’s story, can fail all too easily. You’d be better off watching Paul Dini and Bruce Timm’s Superman: The Animated Series and Justice League to get a sense of where you can go when you have a Superman who wants to believe the best about both his earthly and Kryptonian legacies while constantly having to do battle against the corruptions of both.

In Snyder’s film, Superman’s moral challenges seem peripheral. For example, Superman tells Zod that Krypton had its chance, so basically it deserved to die. And with Martha Kent telling Clark he doesn’t need to be the world’s savior, we never get a clear explanation of why Clark would bother. Furthermore, the mountaintop conversation with the ghost of Pa Kent only seems to hammer away at the fact that collateral damage is unavoidable so Superman can’t help but kill a few people accidentally. Had this conversation taken place in Man of Steel, it would have made perfect sense as a part of his argument that Clark should not become a hero. In Batman v Superman it comes off like a defense of collateral damage, which not everyone believes was unavoidable.

2. The gods and devils the script doesn’t know

As if there wasn’t trouble enough in the plot of Batman v Superman, there remains the question of why Lex Luthor took the trouble to manipulate them into fighting each other in the first place. Any other Luthor might have just grabbed some Kryptonite and kept it simple. Here’s where the film begins invoking religious images and themes without showing us any reason to think the screenwriters understand them.

Luthor spins different yarns about how Kryptonians in general, and how Superman in particular, are either God or the devil, depending on his auditor. I just can’t muster up the ability to suspend my disbelief when Lex Luthor lectures a Senator from the Bible Belt about the devil, as if she’d never heard about Satan at a Sunday school session; Senator Finch hardly seems like the kind of person who would take kindly to condescension. But she lets the moment pass. That seems like a scripting problem that is emblematic of larger thematic puzzles in the film.

Luthor says to Senator Finch that the oldest lie in America is that power can be innocent. But if this were a script committed to sticking to religious themes Luthor could have said that what makes America different is how we’ve handled the Faust legend: Only Americans could retell the Faust legend so that the American can make a deal with the devil and get away with keeping his soul. The historian Jeffrey Burton Russell pointed out precisely this quirk in American versions of the Faust legend in his five books on the history of thought and literature regarding the devil. Americans want to have their cake and eat it, too—to make that deal with the devil for power and riches while still keeping our souls. If the script were to have given Luthor a coherent perspective on America and its literary relationship to the devil this would have been a simple way to go.

But…when Luthor is talking to Lois Lane and Superman later in the film, the comparison is inverted. The Kryptonians are no longer devils from the sky. Superman becomes God, who can only be either all-powerful or all-good. The script, which was so set on attempting to use clever quotes, failed to use the old Baudelaire maxim, “If there is a God, he is the devil,” a turn-of-phrase which is arguably the one and only way to make sense of Luthor’s otherwise incoherent religious ramblings.

But…when Luthor is talking to Lois Lane and Superman later in the film, the comparison is inverted. The Kryptonians are no longer devils from the sky. Superman becomes God, who can only be either all-powerful or all-good. The script, which was so set on attempting to use clever quotes, failed to use the old Baudelaire maxim, “If there is a God, he is the devil,” a turn-of-phrase which is arguably the one and only way to make sense of Luthor’s otherwise incoherent religious ramblings.

So in the final act Lex Luthor, who has spent the majority of the film lecturing people on the peril of the Kryptonian invaders, hijacks Kryptonian technology and builds his monstrous Doomsday gambit. “If man won’t kill God, the devil will do it,” Luthor assures us. But why use the devil’s weapons to kill the devil? Won’t that make you party to the devil’s tricks? If this Lex Luthor is so against the Kryptonians in general, and Superman in particular, then it doesn’t gel with this character that in the final act his plan is to revive a Kryptonian in the hope that he can make the zombie Zod-turned-Doomsday into his puppet.

For comics fans, the appearance of the winged Parademons in Bruce Wayne’s nightmare signal that Darkseid is eventually going to show up, and there are reports of cut scenes in which Luthor talks to someone about Darkseid. This would reinforce rather than solve the problem of why a Lex Luthor so adamantly against alien involvement on Earth would start making deals with conquerors from other worlds. But it also makes his loathing of Superman more rather than less mysterious. The clash between the indirect characterization of what Lex Luthor says about Kryptonians invoking religious images, and the direct characterization of what his actions are in the film never gets resolved. Batman v Superman has a script determined to bring up big ideas without giving us simple, coherent definitions of terms or character motives. Then it dollops us with big plot points that are either in contradiction of the directly and indirectly given character motives on the one hand, or that have no observable connection to the story except some felt mandate to get X and Y iconic comics moments into one film just to say “we did it.”

If the script gave us a coherent take on religious themes and images as well as its primary characters, then Luthor could have condemned the sky-father gods of Zod and Kal-el as needing to be rebuked by the green goddess of the earth mother, or at least the earth mother that can tame the man from the heavens by taking away his powers. Sure, that’s the kind of knowing cheesy pun more worthy of a Gene Hackman or Clancy Brown Lex Luthor than Eisenberg, but it could have worked. Most other memorable versions of Lex Luthor have preferred to use Superman’s earth against him, mother earth as a form of death to the man from the sky. It could have provided some semblance of coherence for Batman v Superman‘s insistent use of religious themes and metaphors. It would have been the thread unifying Luthor’s shift from seeing Superman as a devil talking with Senator Finch and as a god to be killed talking with Kal-el or Lois Lane.

But maybe it’s in that longer film we’re reportedly going to get, the R-rated cut. Perhaps a great deal of footage was cut from the film before its theatrical release. The film we got intstead was a film that tried to bring a cinematic franchise to life out of two famous comic book deaths without showing any signs that anyone got what those deaths were about. Batman v Superman seems both too cynical and incompetent to do right by the interpretive histories of the Judeo-Christian canon its script invokes on the one hand, and the comics canon it has purported to bring to the silver screen on the other.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply