1. Over at the New York Times, Molly Worthen (of Apostles of Reason fame) wrote an interesting piece on the burgeoning learning-assessment industry. For those seeking to hone their “truthseeking” and “analyticity” (!!), teacher assessments aren’t enough; we need big data to tell us what we’re learning. Worthen’s skeptical:

Here is the second irony: Learning assessment has not spurred discussion of the deep structural problems that send so many students to college unprepared to succeed. Instead, it lets politicians and accreditors ignore these problems as long as bureaucratic mechanisms appear to be holding someone — usually a professor — accountable for student performance.

All professors could benefit from serious conversations about what is and is not working in their classes. But instead they end up preoccupied with feeding the bureaucratic beast. “It’s a bit like the old Soviet Union. You speak two languages,” said Frank Furedi, an emeritus professor of sociology at the University of Kent in Britain, which has a booming assessment culture. “You do a performance for the sake of the auditors, but in reality, you carry on.”

Yet bureaucratic jargon subtly shapes the expectations of students and teachers alike. On the first day of class, my colleagues and I — especially in the humanities, where professors are perpetually anxious about falling enrollment — find ourselves rattling off the skills our courses offer (“Critical thinking! Clear writing!”), hyping our products like Apple Store clerks.

There’s really two problems Worthen’s after here. First is that metrics are shallow; they use a part as a measure of the whole, rather like judging an NFL linebacker’s quality by how much weight he can benchpress. Second is that the measure doesn’t always track the reality; there are lots of excellent benchpressers who are not great linebackers. Her point is that marketable “skills” are only loosely related to the actual benefits of an education.

The “two languages” analogy is apt: the official language, which demands constant improvement, is so at odds with the underlying reality, that the two become completely un-coupled. Note that this is what always happens when people’s stubbornly Utopian vision of advancement stops being receptive to reality: the language continues its stately march into a brave new world of buzzwords and bureaucratic policy, while fewer and fewer people talk about the (messy, intractable) reality. Some churchgoers may recognize an analogy here. Anyway, Worthen continues:

Here is the third irony: The value of universities to a capitalist society depends on their ability to resist capitalism, to carve out space for intellectual endeavors that don’t have obvious metrics or market value.

So then one of the roles of education – or, at least, of the liberal arts – is to resist instrumentalization, the tendency to subordinate the things in the world to our personal goals. In a capitalist society, at least for the not-yet-settled young, everything is in motion: social gatherings become networking opportunities, hobby clubs become resume-builders, and reading a novel becomes an occasion to develop the skill of “critical thinking”.

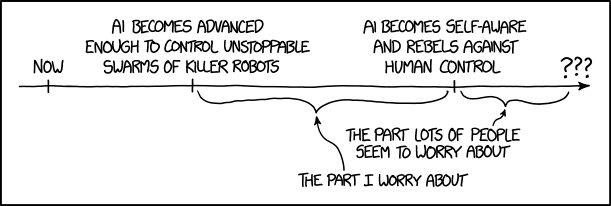

A paradox is that many goods cannot be aimed at directly. The pursuit of happiness often prevents it, for instance., Jumping off from Worthen, it’s possible that if we approach, say, Plato’s Republic as an exercise in critical thinking (as opposed to approaching it as a good thing in itself), then we don’t engage it deeply enough to get even the beneficial side-effect of critical-thinking skills. This paradox throws a fatal wrench into many of our projects for self-advancement or planning out our lives. The process by which a measure of success becomes self-defeating is a subset of that problem which I’ve tried to write about before, but I think the point here is that the human potential to control our destinies and build utopia is always much less than we think it is.

Also, over at New Atlantis, Alan Jacobs looks at the problem of metrics in other fields, arguing that our fixation on them grows out of a world obsessed with standardized, impersonal codes. There’s a brief connection to Charles Taylor’s description of the Modern Moral Order in there, too.

2. How would Christianity speak to the obsession with metrics and advancement? Fr. Stephen Freeman’s excellent Monday devotional has us more than covered there:

There is something buried deep in the human soul surrounding the image of climbing and God. The story of the Tower of Babel is an account of a vast human effort to build a tower that would reach into heaven itself. One of the ancient Ziggurats built by Nebuchaneaer was called, “The place where earth and heaven meet.” Mountains have always played a major role in the meeting place of God and humanity. Our instinct is that we “go up” to meet God.

The Tradition clearly indicates that this instinct has value. But like all human instincts, it has its dark side as well. Our culture’s notion of the “pinnacle of success” is a prime example of this darkness. By its very name, this peak experience is held out as a desirable goal. But we have the strange reality that those at the top are rarely personalities that we would want to nurture in our children. There is nothing that the pinnacle offers other than money and power, neither of which is beneficial to the soul.

This distorted “ladder” often gets translated into the moral life in what is little more than an exercise in Pelagianism. Our struggles for moral improvement frequently have more to do with our inability to bear the shame of moral failure than of any desire for goodness. As such, they are a neurosis rather than a morality. St. John gives us a “ladder” for our consideration. It is worth noting, however, that the fourth chapter in his work concentrates on shame – with the observation, “You can only heal shame by shame.” This is not a “ladder” in any modern sense of the word.

Freeman notes that God isn’t found at the top of our cultural ladders; if anything, God meets people at the bottom (he cites the Beatitudes). I have to make a side-note here that I remain surprised to see the emphasis many in the ‘high evangelical’ world are currently putting on our vocations, which sometimes slips into the notion that advancement in one’s workplace is a spiritual good. (I’d always thought Max Weber was a bit too hard on Calvin, but his idea that worldly success had become a perverse metric of God’s favor still has some resonance.) Freeman reorients us to mundane life:

The ladder of the spiritual life leads downwards rather than up (or it leads us back to where we already are). The lives of the saints are replete with those who abandoned wealth in order to become poor and find God. I can think of no stories in which a saint acquired wealth in order to enter the Kingdom.

I do not think it is necessary for everyone to abandon what they have and head to the deserts. It is sufficient, in my experience, to simply practice mercy, kindness and generosity where you are, and to bear your own failings and incompetence with patience. And, though this sounds easy, it is more than most are willing to do. . . .

We can also know that the good God who loves mankind will never abandon us. No matter how far we may run from the mundane struggles of our existence, the struggles will follow. It is among the promises of Christ: “Sufficient for the day is its own trouble.” (Matt. 6:34).

Amen!

3. At First Things, Patrick Deneen examines the irony that the most strident demonstrations against privilege tend to come from the most privileged institutions. His article ends up as a riff on the mercilessness of meritocracy. What he sees as the new, meritocratic elite remains little more conscious of its privilege than the old elites did. People with good things, including worldly status, may tend to overestimate the degree to which they have earned them or deserve them. For Deneen, the meritocracy’s ‘elite’ schools perpetuate class distinctions, while remaining surprisingly unaware of them:

Of course, it wasn’t the subject of [author] Murray’s lecture [at Middlebury] that was being protested, but the fact that he had discussed statistical differences in IQ among different races in his 1994 book, The Bell Curve. The main point of that book, however, was concern that social sorting would exacerbate class differentiation in America—just the kind of sorting that elite schools like Middlebury help to advance. The violent protests against Murray had the convenient effect of preventing any exploration of the pervasive class divide in America today, and leaving the elite students and faculty of Middlebury self-satisfied in their demonstrative support for equality.

Like so many similar demonstrations against inequality at elite college campuses, the protest against Murray was an echo of resistance of the ruling class to the noble lie [of inequality]. The ruling class denies that they really are a self-perpetuating elite that has not only inherited certain advantages but also seeks to pass them on. To mask this fact, they describe themselves as the vanguard of equality, in effect denying the very fact of their elevated status and the deleterious consequences of their perpetuation of a class divide that has left their less fortunate countrymen in a dire and perilous condition. Indeed, one is tempted to conclude that their insistent defense of equality is a way of freeing themselves from any real duties to the lower classes that are increasingly out of geographical sight and mind.

Deneen goes on to contrast the current meritocracy with the earlier aristocracy. In the idealized form of the latter, elites know their position is not of their own merit, and they see themselves as part of a differentiated whole, which gives rise to the principle of noblesse oblige – responsibility to serve. The reality was quite different–violence, greed, oppression, ‘othering’ of different religious/ethnic groups, etc. Deneen accordingly notes that

We may be quick to agree that there was a gap between the stated ethic of noblesse oblige and the actual actions of the nobility of the ancien régime. But, much like those who took for granted the naturalness of political arrangements during the medieval ages, today’s elites seldom subject their meritocratic justifications of their status and position to the same skepticism.

Just as some people may justify their wealth by insisting that prosperity is solely a function of individual effort, those in the educational elite it seems, may make expiation for their privilege (without ever renouncing it) by focusing on (non-economic) social problems.

Our ruling class is more blinkered than that of the ancien régime. Unlike the aristocrats of old, they insist that there are only egalitarians at their exclusive institutions. They loudly proclaim their virtue and redouble their commitment to diversity and inclusion. They cast bigoted rednecks as the great impediment to perfect equality—not the elite institutions from which they benefit. The institutions responsible for winnowing the social and economic winners from the losers are largely immune from questioning, and busy themselves with extensive public displays of their unceasing commitment to equality. Meritocratic ideology disguises the ruling class’s own role in perpetuating inequality from itself, and even fosters a broader social ecology in which those who are not among the ruling class suffer an array of social and economic pathologies [e.g., opioids] that are increasingly the defining feature of America’s underclass. . . .

Liberalism has achieved its goal of emptying the public square of the old gods, leaving it a harsh space of contestation among unequals who no longer see any commonality. Whether that square can be filled again with newly rendered stories of old telling us of a common origin and destination, or whether it must simply be dominated by whoever proves the strongest, is the test of our age.

While Deneen’s diagnosis seems spot-on, I wish he spoke more on how Christianity served as a check. He gives a nod to the familiar, idealized premodern social Christianity, where everyone exercised their (complementary) gifts for the good of a (corporate – like a body) whole, etc. I’m not saying there’s nothing there, only that it’s ‘thin’, from a Christian point-of-view, and perhaps irretrievably medieval.

So I would add that Christianity’s salutary influence consists in two extra moves: first, there’s an understanding that all are sinners, which puts brakes on any attempt to label someone as morally inferior. I think of Flannery O’Connor’s opening to her story “Revelation”, as the bigoted woman sits in a chair and reflects on all the demographics of people to whom she’s superior. The irony? It takes place in the waiting room of a hospital–i.e., speculating about group differences is kind of dumb when we’re all sinners and we’re all gonna die.

Second, Christianity does have a strong social ethic, one which is as unconditional as God’s love. Neither race, nor education, nor the right political views, nor goodness, nor anything at all serves as a precondition to God’s love. The trouble with no-fault inclusivity (inclusion because we’re all special and all have something to offer) is that it loses its ability to love the second it encounters real, intractable sin. So radical inclusivity must come from God’s love for the least, since if the chief of sinners (1 Tim. 1:15) is part of the family, there is no basis for excluding anyone else from it. This radical inclusivity touches down in the individual life when that individual recognizes herself to be the chief of sinners, but loved. So secular inclusivity assimilates good, finding it in more places than we thought it was, while Christian inclusivity assimilates evil, with the God who died for all while all were yet sinners.

And our collective origin story remains timeless, as the New Yorker reminded us this week.

4. Also–Snoop Dogg has released a 32-track Gospel album (Bible of Love)! Some details:

While some may be puzzled by the sudden shift, Snoop insists it has been a long time coming. His mother is an evangelist and his late grandmother was the driving force behind the project.

“After my mama heard the record she turned around and looked at me and said, ‘I’m not impressed. God told me you were going to do this a long time ago. You have been doing your thing and now you’re doing His thing,’” he told TheGrio in an exclusive roundtable interview.

Snoop anticipates his Christian critics:

“For those who have something to say, their spirit ain’t right. If it was right, the first thing you’re going to do is welcome someone like me who has been where I have been and done what I have done.You’re gonna say, ‘maybe he can reach people we can’t reach. Maybe he’s doing what God’s work is really supposed to be doing.’ The Bible says Jesus was in the streets mixing it up with the real. Everyone sitting in church like they’re perfect, knock it off.”

For a sympathetic review that’s got me excited to listen to it, look no further.

Strays: In a wonderful example of grace in practice, Pope Francis will be washing the feet of inmates in Rome’s main prison during Holy Week. Some Star Wars guys are actually staking a lot on the religion of the Force–check that midichlorian count. In humor, McSweeney’s riffs on workplace trends in a recommendation against hiring Bartleby as a Scrivener. The forthcoming Mr. Rogers documentary looks like a goldmine, judging by its trailer, below. Speaking of which, on the new episode of the Mockingcast RJ, Sarah and Dave tell stories about Mr. Rogers before talking deconstruction, doubt and good news. (Also, Sarah shares the recipe for her favorite Holy Week treats).

COMMENTS

2 responses to “Another Week Ends: Self-Defeating Measurements, Neurotic Moralities, Self-Justifying Meritocracies, and Gospel-Centric Snoop Doggs”

Leave a Reply

really great weekender, W