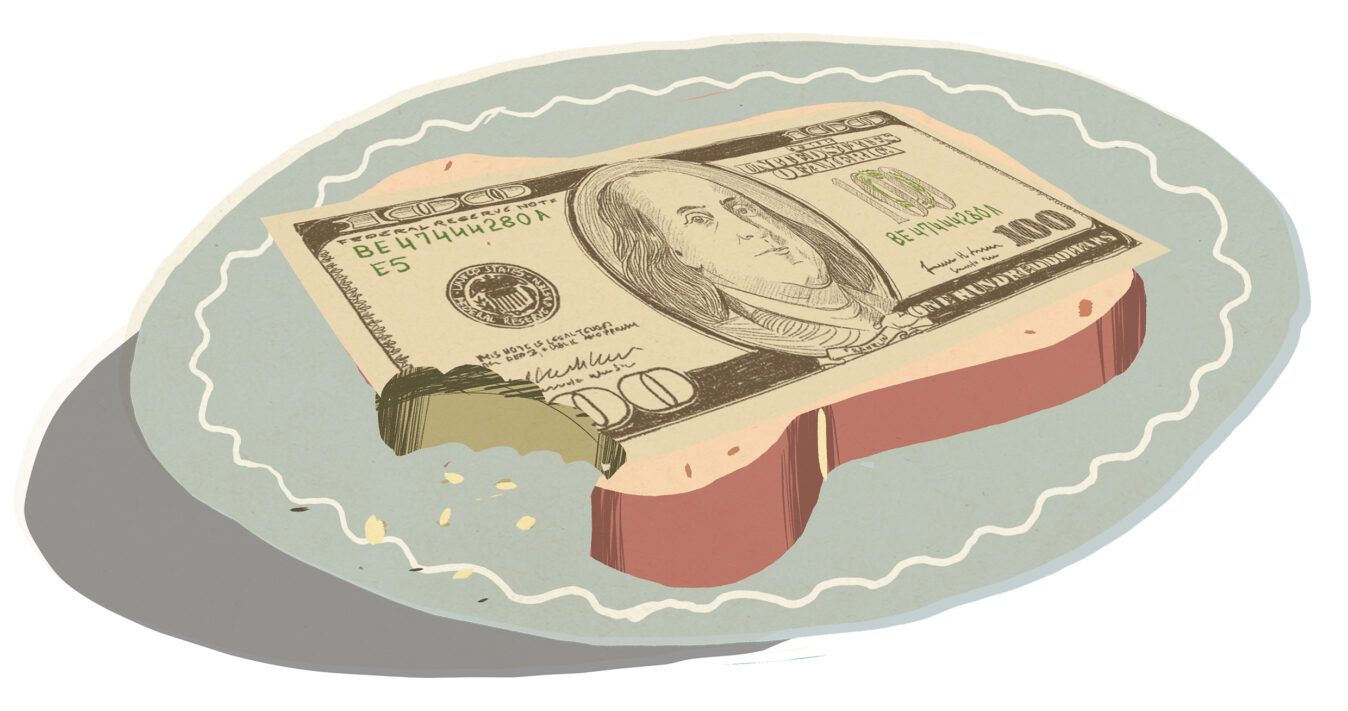

This interview was conducted by Todd Brewer and appears in a slightly longer form in the Money Issue of The Mockingbird magazine.

“Innovation replaces tradition,” the journalist James Surowiecki once wrote, summing up capitalism. “The present—or perhaps the future—replaces the past. Nothing matters so much as what will come next, and what will come next can only arrive if what is here now gets overturned.” Which means that capitalism, at its best, calls into being what never was before. At the expense of unprofitable industries or traditions, it propels us into the future.

Perhaps, in some time and place, all of that was true. But in today’s finance-dominated system, the theologian Kathryn Tanner noticed the exact opposite: “Present and future are captive to the past,” she argues in her book Christianity and the New Spirit of Capitalism. The current system relies on individuals who “amass credit card debt or take out payday loans, at exorbitant rates, to make ends meet.” They are bound, as if by a chain, to previous transactions, dragging them wherever they go. As Tanner sees it, “[N]othing more is to be expected in the future than what the past has already laid down.” You cannot invest in your children’s wellbeing if you are still digging yourself out from your own debts. Tanner contrasts all this with Christianity, in which, she says, we are “counseled to repudiate” the past. “One is not to be who one was before.” Consider Paul’s famous line from 2 Corinthians: “If anyone is in Christ, he is a new creation. The old has passed away; behold, the new has come.”

The author of several books, including Economy of Grace, Tanner takes seriously the idea that Christianity involves some kind of economic vision. She paints it as a religion of possibility, in which the future is unbounded, free. Max Weber famously argued that Christianity shaped early capitalism; essentially Tanner inverts his claim. Christianity, she says, can also critique capitalism, especially finance-dominated capitalism.

As we began sketching out this issue, Tanner’s name came up repeatedly, and for good reason. At the intersection of modern finance and theology, there may be no one better qualified to speak. Here we discuss the religious demands of the economy, as well as its influence on what we commit to. Tanner spills some tea on Luther’s complicated view of work, and she makes clear that grace is precious for the same reason it’s dangerous: it’s free.

MOCKINGBIRD

How does capitalism influence what we desire? I’m thinking not only in terms of consumer goods but also in terms of things that we might not immediately think of as economic, like personal relationships.

KATHRYN TANNER

That’s an interesting question. Particularly in this book (Christianity and the New Spirit of Capitalism), I don’t much use the term “desire,” probably because it’s associated—in Christian ethics and theological circles—with a critique of consumer desire. I wanted to shy away from that more individualist way of looking at things.

But I do consider forms of commitment, especially in a chapter called “Total Commitment.” And if you’re talking about commitment, you’re talking about desire. I mean, what’s the object of your desire? What are you committed to?

Our new economic configuration doesn’t just require you to go to work and act like a good worker while you’re there, but it requires you to be totally committed to your work.

This is something that holds at both ends of the economic spectrum. It’s true for white-collar workers or people in tech or whatever, whose understanding of self-realization is tied up with work. But it also holds true for a whole host of lower-level workers who are required to work around the clock, really, in order to make a living.

I’m contrasting the total commitment of Christians—they’re totally committed to God—with the total commitment that you’re asked to provide within capitalism. And I’m arguing that total commitment to God is a different sort of commitment, with a different structure. And it’s certainly less dehumanizing, for lack of a better word.

M

The total commitment to occupation—even ministries require this, and it’s presented as a kind of holy calling. “Sacrifice everything at the foot of the cross for the sake of the life of the world.” That sounds great, but in practice it can really go the wrong way. You’re not simply investing your time. You’re also investing your emotional capital, so to speak.

KT

Today, capitalism requires not just commitment to one’s job but also commitment to one’s family—home life—in particular structures under current capitalist conditions. It used to be the case that you’d contrast what happened within the home with what happened at work. But now there isn’t much of a difference in terms of the fundamental structures in both places. Like, in every case you’re required to maximize your assets. It could be your personal assets, in the case of your home life, or the assets of your children. You need to get them up to speed, so if you have the wherewithal, you need to take them to soccer and then to music lessons—you’re not talking about just opening the door and letting them play or whatever. That’s out. Now you have this total commitment, because you worry about what’s going to happen to them if you don’t do this stuff. You worry that eventually they’re going to be left behind in the current economy.

M

Yes, I’m very familiar with that. You can’t just send your child to a daycare. You need a daycare that teaches them Mandarin. Or your child needs to learn science while at summer camp, all for the sake of preparing them to enter into the economic system that requires that total commitment.

KT

They’re already totally committed when they’re 10.

M

As I was reading your book, one of the things that came to my mind is that people routinely use economic metaphors while talking about everything from moral choices (like whether it’s “worth” it to do this-or-that), to what to do over the weekend (i.e. how I might “spend” my free time). How do capitalist metaphors influence our day-to-day decision-making process in that way?

KT

The dominant worldview is economic, so that pretty much co-opts everything else, including language and metaphor. And it’s not just a cultural dominance. I assume that in a neoliberal economic state—in contrast to a liberal economic state—where it’s kind of hands-off and you don’t want the state mucking around, the state is basically subordinate to economic interest. So the economic way of looking at things is just what you naturally fall into. That’s the way the world is. Why wouldn’t you think that way?

Christians tend to do that, too, just because everybody does that. Part of what I’m trying to do in the book is to consciously resist this. But first you have to be aware that it’s going on. Only then can you say that Christian categories aren’t like these categories, that they’re being deformed in some way when they’re pushed into this economic framework.

I’m not assuming that there’s a realm that’s non-economic in character. Often you’ll find people, like Michael Sandel or whoever, assuming that the home is not economic, that it’s pristine. I don’t believe that. But I do think that a Christian way of looking at things should resist some of this economic analysis that people fall into.

And certainly you see this issue in higher education all the time. Like, why are we talking about students as consumers and questioning the value of faculty productivity? As academics, we have to do all this auditing. It’s not even so bad in the United States. In the UK it’s horrible. It’s all economic. We’re always asking, What’s our product?

I mean, we don’t need to think this way, and actually, 15 years ago, people didn’t think this way. But that outlook certainly infiltrates every cultural domain, and it certainly infiltrates the religious domain. And people don’t even realize it’s happening.

M

Like friendship, for example, right? We can conceive of friendships as investments, where what I put toward you should return to me in kind or in excess. But in true friendships, a person may not be a “good investment,” so to speak.

KT

Yeah, nowadays when we think about friendship, we often wonder what we’re going to get out of it. That’s networking, which has an economic payoff.

I don’t actually think that’s much different from friendship in, like, the ancient world—you know, there were forms of patronage, which was an economic relationship. It was about maintaining a certain sort of social order and reaping the benefits of that social order. So again, I don’t think friendship is some pristine, non-economic realm.

But I don’t think reciprocity is a primarily Christian value, either. I’m more of a unilateral-giving-and-unconditional-access person. That’s in Luther, for example.

M

Say more about that.

KT

Lissák Tivadar, from FORTEPAN ©2010-2014.

Well, I was just reading On the Freedom of a Christian for my Systematics class, and there Luther says, God has given freely to you, so you’re obligated to give freely to others. It’s a kind of conduit thing. But of course, in most of Luther’s other writings, he’ll immediately pull back and say, Oh, but we can’t do this in ordinary life; that’s not allowed. But with On the Freedom of a Christian, there are major socio-political implications.

And that means open access. If you want to make it concrete, you could talk about open access to universities and community colleges. Basically, things are free. You don’t have to meet a requirement. You don’t have to work in order to get welfare benefits or say you’re going to look for a job.

I mean, personally I’m anti-work, but that’s a good Lutheran principle, too! I’m just applying it beyond where Luther tended to apply it. I mean, if he’s against works, he’s against works! Let’s put it out there. That’s the vulnerable part of Luther’s position: when he talks about the value of ordinary work or occupation. He interrupts the obvious anti-works implication, that he’s drawn from grace, which has socio-political applications that are quite radical.

M

Yeah, he does pull back. It’s like Paul in Romans 11, where he draws close to what could be a kind of universal salvation. And then, as soon as he gets there, he breaks into doxology.

KT

Yeah. He’s like, Who knows? We’ll leave it up to God.

M

Similarly, Luther’s constantly making these outlandish claims—compelling ones—and then saying, Well, let’s be practical.

So you want to take Luther at his first word and not at his second.

KT

I think he’s being grossly inconsistent by not applying grace socio-politically or economically. It’s for obvious reasons that he wouldn’t: You’re not going to get the support of any state leader if you start talking that way. And there could be other reasons, I’m sure.

M

An economist might say, Free stuff is totally impractical. You can’t do this.

KT

Well of course it’s not actually impractical. Basic income, that’s been tried. There’s no reason why education can’t be free. There’s no reason why healthcare can’t be, for all intents and purposes, free. You talk about universal healthcare, that’s what you’re talking about. The money has to come from somewhere, sure, but actually, there’s quite a lot of money in circulation. It just depends on what you want to use it for. And if there’s one thing that finance teaches you, it’s that money makes money, infinitely. There’s no endpoint. It’s just that right now, it’s all going into the pockets of certain people who are flying to Mars or whatever.

M

But is it the case, in the here-and-now, that there’s a real superabundance—an excess of wealth?

KT

I think that only holds for God. I don’t think there actually is abundance generally speaking, as a created good. We’re talking about scarcity, primarily.

But I also believe there are false scarcities. Lots of things are done to make it seem as if there is, or to create, a scarcity. For example, a false scarcity is produced when businesses shunt all their profits to the top; then there seems to be a real scarcity at the bottom. There is much more of an abundance than there might seem, because of the ways things are structured.

M

But is it plausible, in terms of economic programs in the real world, that we could closely approximate a Christian understanding in action?

KT

Yes, and that’s usually all I’m suggesting: Let’s approximate. Of course you can’t be God for other people, the way God is for you. That’s impossible. But there can be some form of approximation, and I try to just lay out the kinds of principles that you should be shooting for within a world that’s finite, conflict ridden, etc.

And then also, since I’ve been reading Luther… I mean, I actually have been influenced by Luther, even though I’m not a Lutheran!

M

Me neither!

KT

Let me make that clear. I’m Episcopalian. I only take the best from Luther, and leave the rest.

But the bottom line is, you’re supposed to be committed to love of neighbor, and that involves a lot of difficult work. But it’s not work in a bad sense, because you’re not doing it for any reason besides the fact that it’s a way of expressing your gratitude to God, your love to God. You’re doing it joyfully and lovingly without regard to consequence, really, or what it’s going to mean for you.

I don’t think it means you’re asked necessarily to be self-sacrificial. To the contrary, the language has more to do with abundance: You’ve been given so much, you know, give it again, out of simple gratitude and love for the Giver, without worry, and without anxiety, and that’s what makes it not work in a bad sense.

I don’t think it means you’re asked necessarily to be self-sacrificial. To the contrary, the language has more to do with abundance: You’ve been given so much, you know, give it again, out of simple gratitude and love for the Giver, without worry, and without anxiety, and that’s what makes it not work in a bad sense.

So yeah, if I were doing what my employer wanted me to do, simply out of love for my employer, without worrying about being thrown on the street and starving to death, that would be another matter. But that’s not actually the way that the current system works in the United States. You have no safety net. You have to be totally committed. The company, whatever it says to you about its concern for your wellbeing (or not), is trying to maximize their profit off your back. That’s the opposite of a joyful, loving, grateful (but effort-filled) struggle to benefit others the way God has benefited you.

I mean, that’s right out of Luther!

M

Right out of Luther. I love it.

One of the difficulties, in terms of how people relate to their work, is the debt that they carry, whether that be student loan debt, credit card debt, or payday loan debt.

Can you talk a little bit about debt and its function within the economy and then what that means or doesn’t mean for Christianity? For example, Matthew’s “Forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors.”

KT

Both within Christianity and within the current economic system, debt is front and center. The current finance-dominated regime of capitalism is predicated on debt as a very fundamental way of generating profit. To a great extent, generating profit by the buying and selling of goods is being replaced by getting people indebted whenever they try to buy anything!

And if you’re talking about national economies, they operate not so much via taxation, although that’s part of it, but via debt: They sell bonds in order to finance their operations. And that means they’re indebted and that they have to not just service those debts, but they also have to prove their credit-worthy character, which often leads to austerity measures within the government’s territory.

And certainly that only makes more crucial the way in which debt features within Christianity. So in the Lord’s Prayer, “Forgive us our debts”—debt and sin are pretty much conflated there. Whatever we’re talking about, it’s the same thing. So, you know, when you’re talking about God’s forgiveness of our debt, it’s crucial within Christianity how you understand that to happen.

I argue, as a theologian, that your debts are wiped out, and so are the consequences of those debts, by virtue of the Incarnation and not by way of legal mechanisms that have to do with vicarious punishment. Basically, I don’t think that God’s relationship with us should be understood in contractual terms at all. And therefore, you shouldn’t talk about what Jesus is doing on the cross as fulfilling the terms of a contract. Protestants tend to talk this way, unfortunately.

M

But Luther most certainly didn’t. He pushed back against the pactum theology; that is, the idea that we fulfill our end of the contract, and God does the same.

KT

That’s how I read him, too. I think Luther is going back—and Calvin, too—to the church’s early understanding of grace, which has everything to do with God’s presence, unity with God, Incarnation.

It’s the Happy Exchange model. That is not a legal or contractual model. Somebody gives you what is theirs, and you may assume that what is yours is also theirs. It’s a property exchange, but it’s in virtue of a very close relationship—the unity of the human and the divine in the Incarnation. And the point of the exchange is that humans should enjoy the property, if you want to call it that, of God. That’s not a fulfillment of a legal contract.

In the modern period, you can certainly see that contractual, legal, economic language. We’re making a deal; I’ll give you this, and then you give me that. To the extent that that infiltrated what Protestants mean by a covenant, I think that’s terrible. Not a good idea at all.

M

It even affects interpersonal relationships and how we “deal” with other people. Do we deal with them on a contractual level, or do we deal with them in terms of unilateral action, irrespective of standing?

KT

It affects our understanding of community. The old patristic image, which Luther uses, again in On the Freedom of the Christian, is the fire and the iron. The iron starts to glow with the fire, because they’re so close together. That’s what happens in the Incarnation. That’s what happens in grace. But the implication of that for social relationships is that you see a very, very close community with others, and it’s not me and them, and I’m giving something to them as a form of philanthropy, but we have a mutual interest. That’s economic language, but you see what I mean?

For example, if there is a suffering person on my block, I can’t isolate myself from that person by closing the door or stepping over them or whatever. I can’t absent myself from a relationship with them, a relationship that is so close it can’t really be broken. And what that also means is that I need to offer to them what I have. This doesn’t involve the usual philanthropic understanding of stuff, in which one thinks, “I’ve accumulated all this stuff and now I don’t know what to do with it, so I’ll give it to people I don’t know.”

M

We tend to wrongly assume the Good Samaritan is rich.

KT

Yeah, I’m not saying there aren’t disparities. It’s just that it’s not accidental or optional that I would offer my resources to the suffering person, because they already own those resources, in virtue of their relationship to me. What’s mine already is theirs, and I’m just making that clear. So yeah, in the reading of the Good Samaritan…

M

The questions is, “Who is my neighbor?” Right? So it’s not about philanthropy in that way.

KT

Right, that’s true.

M

It’s a model of what you’re saying—of the interconnectedness between people.

KT

Yes. I’m already connected to my neighbor, to this person. And it’s a mistake to think that I can isolate myself from them. Think of the marriage imagery. Not that I usually use this imagery, probably for obvious reasons, but Luther uses it, again in On the Freedom of the Christian. The husband’s property is the wife’s, and the wife’s property is the husband’s. And it’s because they’re married.

So in the case of the person on the street, I’m also married to them, in a sense. What’s mine is theirs. And what they have is also mine, meaning their suffering is mine.

Where I live, in New York City, there are people who are clearly not doing well; they’re drug-addicted, they’re homeless, they’re on the street, and they’re right outside my window. So it’s not as if what they’re doing is unrelated to me. It absolutely is.

M

I didn’t realize you live in New York. You know the controversy about the Upper West Side—how they were going to convert some of the apartments and hotels into housing for homeless people? That caused such an uproar in that neighborhood.

KT

Yeah, I know what they’re talking about. I mean, like, the bongo-drum man was just drumming nearby me, and he does that all the time. I wish he weren’t drumming the bongos right now. He’s obviously not employed, and he doesn’t have to worry about what hour of the day is most appropriate for drumming when it comes to employed people like me down the block.

Or somebody’s shooting up right outside your door, leaving the needle there for your child to step on.

My point is that if there were more resources directed to drug addiction, or hunger and unemployment and poverty, etc., we would all benefit together. Not just those people whom we typically think of as needy. There would be mutual benefits.

M

How might a Christian understanding of God and God’s grace be, perhaps unconsciously, influenced by a kind of modern capitalist finance worldview?

KT

J. L. Peterson, Lilim parviflorum (Wild Tiger Lily), 1920.

Well, grace can be distorted in a number of ways. One way has to do with what I’ll call individualism, but it’s not what people ordinarily mean by individualism. By individualism, I mean that you have to take individual responsibility for everything.

So whether you’re saved or not, say, would be a matter of your own individual responsibility. That’s one example. It’s comparable to being in the current United States, where basically you have to save yourself. If you’re going to make it in the world, that’s your own responsibility. If you fail, even if it’s the result of accidents, then you’re going to pay for it. Nobody’s going to help you. Those ideas infiltrate our understandings of what it means to be saved by God, what it means to be graced, what it means to be justified.

But then another whole set of issues has to do with competitive relationships with others, so that if I get ahead, I’m doing it at the expense of somebody else. Or there’s some necessary trade-off—it’s a zero-sum game. I think Christian understandings of grace should be directly opposed to zero-sum games, which tend to be elitist in character.

If there’s some kind of competition in spiritual achievement, then people are ranked in terms of how far they’ve gotten spiritually. Christians are prone to thinking that way, and I think that’s a mistake. That’s just the usual competitive kind of relationship among people in, like, corporations. Who’s going to get the bonus? Well, the big earner gets the bonus.

It’s a comparison-oriented valuation. That’s a very insidious thing. On this basis, Nietzsche does a great job of criticizing Christianity, which in his view is always concerned with a comparison that involves a negative evaluation of somebody else. So I’m only great to the extent that you’re not, rather than just valuing oneself for oneself.

M

In your book, you write about data, which is really interesting to me. We attempt to use data to optimize the future based upon the past, right? We’re guessing what’s going to happen based on what’s happened in the past.

What are some ways in which a Christian understanding of time is different? Are we bound by our past? Or is there something else?

KT

I’m looking at questions like, how do you relate to your past? How do you relate to your present? How do you relate to your future? I’m trying to suggest that we should leave the future open in ways that would allow us to criticize the present—to suggest that things don’t always have to be this way; they could be different. So there’s an openness to the future, where we’re allowing it to be a future that’s not continuous with the present, that’s radically different from it and therefore unpredictable. That’s in keeping with the idea that you do what you do simply out of a commitment to God, without concern for whether this is going to be successful or not, without concern about the future.

But it’s also a very present-oriented position. But it’s not like, “I’ve got to do something now, or I’m going to go down the drain.” I think current forms of capitalism foster a sense that the present is an emergency. But it’s more that God’s grace is giving you everything you need right now, and therefore you don’t need to be anxious about what’s going to happen tomorrow.

It accompanies you at every moment of time, this sense that you’re loved by God and graced by God, and nothing can impede that, not even your own continued stupidity or sinfulness or whatever. That’s very different from the chained-to-the-past attitude that results from debt, unforgivable debt—you know, you have student loans until you’re 95.

Kathryn Tanner works (if you can call it that) at Yale Divinity School. She does as little as possible, by design.

Illustration by Lehel Kovács.

[…] After years of writing about workism (aka “the religion of work” aka “the Protestant work ethic”), we are today seeing a strange amount of not-work — and an attendant panic about it. At the […]

[…] job, and those other callings may actually be more important to God’s purposes. Or, as Yale Divinity School’s Kathryn Tanner observed in the Money Issue of The Mockingbird magazine, Martin Luther stops short of asking what the socio-economic implications are of having an […]