Must have been almost fifteen years ago. I was sitting down with the chaplain of a prestigious New England prep school, and although he was being incredibly polite about it, he was sussing me out. You see, I was a stranger on campus, brought there on behalf of the para-church organization for which I worked, at the invitation of the school’s Christian fellowship group. He had every right to know where I was coming from before signing off on my presence/involvement, a responsibility to parents and administrators to ensure that students would be spared any high-pressure proselytizing while away from home. Which is to say, I had expected this.

After some minimal small talk, he told me that, in his view, the message of the Gospel was about “God’s radical love for the outsider”–that that was the kind of spirit he was hoping to cultivate in his ministry there. Absolutely and amen, I concurred. He seemed surprised to find so much common ground.

After some minimal small talk, he told me that, in his view, the message of the Gospel was about “God’s radical love for the outsider”–that that was the kind of spirit he was hoping to cultivate in his ministry there. Absolutely and amen, I concurred. He seemed surprised to find so much common ground.

As I drove away that day, I replayed our interaction in my mind, wondering if I should be vaguely insulted. What about me would have led him to suspect I wouldn’t be on board with such a statement? What was the alternative–the Gospel as “God’s highly-qualified love for the insider”? Doubtless he wouldn’t have vocalized as much, but the perception was telling. My employers were more evangelical than the school’s administrators, but so was pretty much every professing Christian in the surrounding fifty states. Given what else was “out there”, the organization I represented was a bastion of thoughtfulness, kindness, and respect. To his credit, the chaplain recognized as much and in the end could not have been more welcoming or accommodating.

The interaction stuck with me. I would soon come to learn that the phrase–“God’s radical love for the outsider”–was something of a mantra in mainline circles, as much a political statement as a theological one. But that didn’t make it less true. Looking back, I suspect we understood its meaning quite differently, especially the words “radical” and “outsider”. More on that at the bottom.

What brought the phrase back to mind was trio of things: 1. The sermon I was assigned to preach this past Sunday on Luke 4:21-30, 2. The fantastic new single by Suede, “Outsiders” (below), and 3. The article that appeared in The NY Times a few weeks ago by Arthur Brooks on “The Real Victims of Victimhood”.

Most criticism of “victimhood culture” focuses on the challenges it poses to education, particularly the liberal arts, but Brooks widens the circle to show how much victimhood has come to characterize our embattled political climate (and not just on the Left):

“Victimhood culture” has now been identified as a widening phenomenon by mainstream sociologists. And it is impossible to miss the obvious examples all around us. We can laugh off some of them… Others, however, are more ominous.

On campuses, activists interpret ordinary interactions as “microaggressions” and set up “safe spaces” to protect students from certain forms of speech. And presidential candidates on both the left and the right routinely motivate supporters by declaring that they are under attack by immigrants or wealthy people.

So who cares if we are becoming a culture of victimhood? We all should. To begin with, victimhood makes it more and more difficult for us to resolve political and social conflicts. The culture feeds a mentality that crowds out a necessary give and take — the very concept of good-faith disagreement — turning every policy difference into a pitched battle between good (us) and evil (them).

Only qualification I might offer would be that I hear ideological differences chalked up to insanity just as often as evil. But either way, the net result of a victimhood culture run amok seems to be, ironically enough, an across-the-board increase in dehumanization. We seldom think of “those people” as actual people. Individuals are flattened alongside their arguments and opinions, objectified.

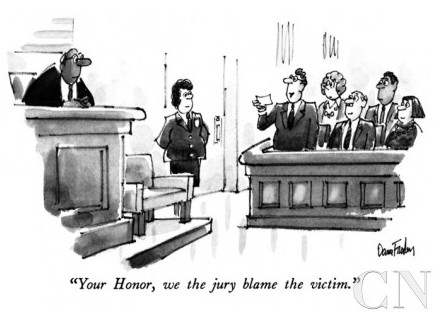

Take for example, the phrase “victim-blaming”. Anyone who spends much time on the Internet has stumbled upon it in a comments thread or clickbait title. The origin of the phrase is undeniably noble: to protect those who have been legitimately victimized and curtail cycles of abuse by policing rationalizations such as “she was asking for it”, wherever they might appear, in the hopes of snuffing out the thinking behind them. In one sense, nothing could be more compassionate or urgent. Yet where once upon a time the term was reserved for matters pertaining to sexual assault or domestic violence, today you see it used in relation to social media gaffes.

The parameters of what constitutes victim-blaming, in other words, have been vastly (and irresponsibly) expanded. What hasn’t changed, though, is that you do not want to be accused of victim-blaming–however trivial the circumstances may be. It signals the height of callousness and/or privilege, essentially a nuclear option in the rhetoric of identity politics.

Indeed, it feels callous to even pause over the phrase, such is its unassailability. The only reason I dare do so is because the prohibition on “victim-blaming” seems to be resulting in the widespread notion that victims are, by definition, blameless–or to use a religious term, righteous. Perhaps it sounds like a minor distinction, but the logic is worth spelling out: by virtue of something unrighteous (or anti-righteous) happening to a person, they are made righteous, sanctified. An act of malice or injustice doesn’t just injure the victim, it somehow absolves them, often reducing their humanity to a single act or attribute. Grievance thus becomes a new form of moral currency.

Brooks goes on to make the controversial claim that “victimhood culture makes for worse citizens — people who are less helpful, more entitled, and more selfish”. On a macro-level, his words might come off as insensitive. But anyone married to a self-pity addict knows that the more calcified one’s grievance becomes (around one’s identity), the more love gets shut out of the picture.

A victimhood culture romanticizes those who have been “done unto”. You might say that it doesn’t so much soften the line between insider and outsider as invert and underline it. Furthermore, it collapses a person into their wounds, and possibly even trivializes them. After all, given what human beings are like, if you look hard enough, you’re likely to find a reason to feel victimized–just take a gander at our political climate.

Back to our chaplain friend. When he spoke of outsiders, I’m fairly certain he was referring to those who had been marginalized by forces beyond their control, predominantly socioeconomic ones. People with genuine, often heartbreaking grievances, the victims of systemic injustice. His job, then, entailed motivating the “insiders” (those at the school) to reach out to the less privileged–in love. A noble and worthy program, to be sure. It was just that the conception of God’s love lurking underneath his vision was far from radical. It cast God as favoring the blameless, a contemporized version of the default ‘God loves the good little boys and girls’ trope. Moreover, it doubled as a way of keeping the core message at arm’s length, gearing it toward those other people over there. Follow the thread and you get a paternalistic us vs. them mentality which ends up restricting God’s love rather than expanding it. Perhaps I’m not giving him enough credit. Lord knows he was just another overworked teacher doing his best.

Again, what brought it to mind was the episode at the end of Luke 4, where Christ’s hometown audience tries to throw him off a cliff after he refuses to entertain their insider status. Every commentary or sermon I found online positioned the story as an epiphany of “God’s radical love for the outsider”–which it is–but then used it to exhort churchgoers to be more compassionate and generous with those on the other side of the tracks, i.e., a call to social justice. Which is never a bad thing, of course. If only it didn’t rely on some dodgy theology. Because to interpret the passage that way you have to put your hearers in the role of God rather than creature, parent rather than child, subject rather than object, and ignore the extent to which we are all outsiders–yes, even the most insider-looking/-seeming person among us. As Mary Karr once so eloquently expressed:

The most privileged, comfortable person in this auditorium, from the best family, has already suffered the torments of the damned. I don’t think any of us get off this planet without suffering enormously. And one of the chief ways we suffer is by loving people who are incredibly limited by the fact that they’re human beings, and they’re gonna disappoint us and break our hearts…. We are all heartbroken. It’s the human condition….

Life makes victims of us all, I suppose. Then again, perhaps all this sounds a bit too much like something an ‘establishment’ person would say by way of justification. It probably is, at least in part. But that doesn’t necessarily make it any less true–or radical in its inclusivity.

To drive his point home, Jesus references two stories from the Old Testament (4:25-27), both of which involve prophets passing the Israelites over in favor of gentile stragglers, in one case a widow and in the other, an enemy general stricken with leprosy–outsiders in the extreme. Yet in both cases God comes to them not because their outsiderness imbued them with a fresh or glamorous kind of righteousness (to merit his attention), but because there was no pretense about them having any in the first place. Meaning, what’s radical about God’s love in those instances is how it targets the unrighteous. The sinner.

The Nazarenes balk at being put into that category–the mere suggestion of being placed on level ground with unclean Gentiles enrages them to the point of violence. Miraculously enough, Christ does not retaliate against his murderous neighbors. He allows himself to be cast out, victimized, made an outsider, so that he might continue “on his way”–a path that would eventually, well, you know where he was heading.

A week after I sat down with the chaplain, I visited the fellowship in question. It was a Friday evening in winter, and we met in a wood-paneled room with a fire going. Kind of a Hogwarts vibe. There were about fifteen of us total, a ridiculously diverse group: a few preps, a handful of international students, a couple of athletic-looking seniors, some bookish first-years, boys and girls of every race were represented. The admissions office missed a major photo-op.

After everyone introduced themselves, they shared their high’s and low’s of the week. Usually high school students aren’t forthcoming, but not this bunch. They talked about how lonely boarding school was, not just as Christians (though that too), but as human beings. They told me about the pressure they felt to fit in, the masks they were expected to wear, how hard it was to connect with classmates that you were supposed to be competing with, the burden of parental expectation, the sheer amount of work involved in staying afloat. Another project was the last thing these kids needed. They were starved for comfort. TLC with no strings attached.

The Gospel of Luke was on tap for that evening, believe it or not, the fifth chapter. We read the passage where Jesus called Levi, and I could see color returning to faces. It was radical.

COMMENTS

11 responses to “The Outsider Gets Radical: Notes on Blaming the Victim and Loving the Alien”

Leave a Reply

“Life makes victims of us all, I suppose. Then again, perhaps all this sounds a bit too much like something an ‘establishment’ person would say by way of justification. It probably is, at least in part. But that doesn’t necessarily make it any less true–or radical in its inclusivity.”

Nice. Thank you David.

I serve in the Lutheran tradition.

I distinctly remember hearing in seminary, I am not exactly certain who said it – it could have been Forde – that there is a “Lutheran suspicion.”

And that suspicion is that we are ALL trying to justify ourselves.

That is our default way of dealing with things. . .

The good and right and important insight, that we should not blame the victim, WILL be used for self justification. The self will use any and all available tools in the self-justification project.

Wonderful piece, David! (especially the end of the story)

Woof. Yes.

Thank you.

Isn’t playing the victim our natural instinct? Not only are we victims, but we want to be. When Adam was found naked with fruit juice still in his beard his first response was to blame the woman who had “done unto” him. She in turn blamed the serpent. In our minds, we escape moral responsibility for what we have done and, even more, who we are by attributing our actions and what we have become to the people around us. It’s hard to tell who is really a victim when we all want to be so badly. And what a great quote by Mary Karr.

Love this, thank you DZ.