Many people mistakenly think that we Mockingbirders have a low view of God’s Law. Some even call us (dramatic pause) antinomians. I know, I know. I’m as shocked as you are, but there it is. (In case you don’t know, antinomian is the fancy theological term for someone who thinks that Christians, because of God’s grace, can now go about the business of fulfilling all their little immoral whims. They are “anti” (against) God’s “nomos” (law).) The Apostle Paul, the guy who wrote half the New Testament, was accused of this (see how he responds to his critics in Romans 3.31, 6.1, 6.15).

Many people mistakenly think that we Mockingbirders have a low view of God’s Law. Some even call us (dramatic pause) antinomians. I know, I know. I’m as shocked as you are, but there it is. (In case you don’t know, antinomian is the fancy theological term for someone who thinks that Christians, because of God’s grace, can now go about the business of fulfilling all their little immoral whims. They are “anti” (against) God’s “nomos” (law).) The Apostle Paul, the guy who wrote half the New Testament, was accused of this (see how he responds to his critics in Romans 3.31, 6.1, 6.15).

Well, nothing could be further from the truth. The reason we are so big on Grace is because we are big on Law. We hear Jesus’ dictum: “Be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect,” and rather than water it down with language about “good intentions” and “figures of speech,” we take it at face value. As a result, we run pell-mell to the cross of Christ and fling our desperate arms around it.

So we follow the teachings of Jesus, St. Paul, and all Scripture that God’s Law is holy and good. What we question, however, is the idea that the Law on its own can produce what it demands. In other words, were not so sure that telling people what to do actually gets them to do it. Or to do it in a way that pleases God (that is, with all their heart, soul, mind, and strength; one might wonder whether grudging obedience pleases God, as it denies God’s worth; does your spouse like it when you give him or her a gift out of obligation?). In fact, we think that telling people what to do actually often produces the opposite. As St. Paul said (in the Bible!): “Now the Law came in to increase the trespass” (Rom 5.20a, ESV). A command seems, in the very act of its proclamation, to stir up mountains of resistance in the human heart.

Two great examples. First, read this paragraph (from Slate‘s recent article discussed in JDK’s fantastic post below) about what happened after January 1, 1920, when Prohibition went into effect in the U.S.:

But people continued to drink—and in large quantities. Alcoholism rates soared during the 1920s; insurance companies charted the increase at more than 300 more percent. Speakeasies promptly opened for business. By the decade’s end, some 30,000 existed in New York City alone. Street gangs grew into bootlegging empires built on smuggling, stealing, and manufacturing illegal alcohol. The country’s defiant response to the new laws shocked those who sincerely (and naively) believed that the amendment would usher in a new era of upright behavior.

Second, Advertising Age recently publicized the results of a study on ads designed to curb binge drinking:

It has long been assumed, of course, that guilt and shame were ideal ways of warning of the dangers associated with binge drinking and other harmful behaviors, because they are helpful in spotlighting the associated personal consequences. But this study found the opposite to be true: Viewers already feeling some level of guilt or shame instinctively resist messages that rely on those emotions, and in some cases are more likely to participate in the behavior they’re being warned about.

The reason, said Kellogg marketing professor Nidhi Agrawal, is that people who are already feeling guilt or shame resort to something called “defensive processing” when confronted with more of either, and tend to disassociate themselves with whatever they are being shown in order to lessen those emotions.

So there you have it. Prohibition of alcohol caused a 300% increase in alcoholism. And shaming people about their binge drinking gave rise to–surprise!–more binge drinking.

Some might say, “Yes, the Law doesn’t work for non-Christians. But if you’re a Christian, it’s a new day, and we can hear the Law without reacting against it.” This argument, however, fails to take into account the fact that Christians are in process, a mix of old and new. As Luther said, “The Old Adam [our hedonistic sinful self] is drowned in baptism. But he is a very good swimmer!” If you want to say that there’s a part of you, as a Christian, that can receive the law, fine. But keen students of the Bible and human experience might be wise to remember the articles above and be a little more careful about giving advice, incessant preaching of hortatory sermons (whether your pulpit is in a church or at the dining room table), or simply telling people what to do.

What’s an alternative? Rather than law-based appeals to muddled human wills, try this little prayer, chock full of mind-blowing sweet theological truth, which Anglicans/Episcopalians are getting ready to pray this Sunday–in a church near you! (And remember, “keep” here means “maintain in safety from injury, harm, or danger”):

Almighty God, who seest that we have no power of ourselves to help ourselves: Keep us both outwardly in our bodies and inwardly in our souls, that we may be defended from all adversities which may happen to the body, and from all evil thoughts which may assault and hurt the soul; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who liveth and reigneth with thee and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen. (The Collect for the Third Sunday in Lent, Book of Common Prayer, 1979)

Aaron, I agree with the basic premise, but I am at a loss to explain the growing phenomenon of massive binge drinking in Britain, and even now to a lesser extent in Italy. It does not seem to be in reaction against any social or moral imperative not to drink. Any thoughts?

I think in the past month I've used the line: "we don't disregard God's law but, rather, esteem it so highly that we're desperate to admit we fail and are in dire need of the cross" in almost half of my conversations at school. This one combined with Jady's are really timely posts (as well as well written). Keep up the great work, Aaron.

wow. you hit one outta the ballpark!

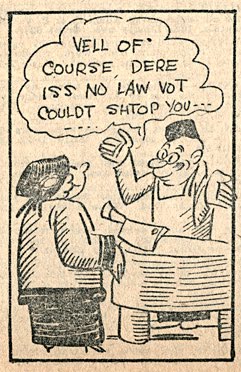

Great call with the Roy Lichtenstein image at the end of the post. I can only imagine what "Brad" must have said/done prior to that moment regarding her own binge drinking … or whatever else. It is a packed image (which could easily go on MBird t-shirts or business cards), and such an explicit example of condemnation and our need of salvation from outside of ourselves. Beautiful!

Thanks, Frank! And, David, I have been a longtime Lichtenstein fan. I remember seeing his work as a kid and just being floored by it. And, yes, it's a thoroughly Mockingbird-ish image–an illustration of the deepest part of human need, alongside a depiction of the human will's fierce ability to resist help. What a clear manifestation of the need for a God who breaks in and breaks through.

Michael–your question is a good one. I think in the US, our drinking habits are largely born out of the kind of social stigma you describe–Prohibition was not long ago, and anyways, the die had already been cast by some of the rigid piety that came out of Puritanism and the successive Great Awakenings (And I'm not knocking either one of those movements–I love many Purituan theologians–just the legalistic fringe that accompanied them). As for what's going on in Europe–sin is not always a result of overt reaction against the law. In some cases, we sin simply because it seems pleasurable, fun, etc. The point of the post was not to explain why we sin. Rather, it was to illustrate the fact that we are already sinners, and attempts to control sin by just telling people to stop (via legislation or guilt-inducing media campaigns) simply exacerbates the problem. Such media campaigns have already begun to combat binge drinking in Europe, and I'm skeptical about their efficacy. The big exception to this I can see is the success of the No Smoking movement in the US. The reason it has worked, I believe, is the way they were able to really stigmatize smoking so that only losers did it. Smoking became seen as dirty and unenlightened. Like driving a Hummer or eating processed food. They were able to appeal to the human desire to self-justify.

Aaron–I agree with all you have said. We have what Paul described as "the law of sin and death" operating within us which drives us to do certain things apart from reaction to any external demand. Binge drinking can be fun, at least in the short term, apart from any external demand not to drink, as a result of my own screwed up human nature. On the other hand, external demand will never fix this, or at least fix it in any way that really matters to God. I don't think God is really into ASBOs. What's that saying about "nothing worse" than a reformed (in the wrong way) smoker or drinker? Those who CAN respond to "just say no" end up twice the sons of hell they were before.

And let us always remember– sure they were a little uptight, but the Puritans loved their beer!