Our pride drives us to establish our own righteousness. We strive all our life to see ourselves as keepers of rules we cannot keep, as loyal subjects of laws under which we can only be judged outlaws. Yet so deep is our need to derive our identity from our own self-respect – so profound our conviction that unless we watch our step, the watchbird will take away our name – that we will spend a lifetime trying to do the impossible rather than, for even one carefree minute, consent to having it done for us by someone else.

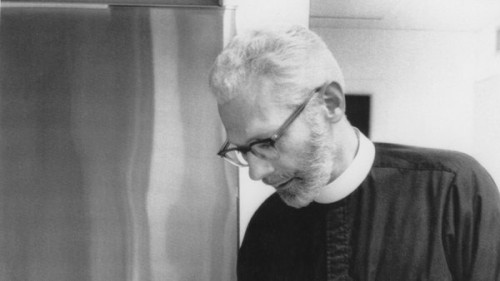

Really, no one says it better. It’s exactly this resistance which Robert Farrar Capon, one of our resident Mockingbird heroes, spent much of his life and incredible stylistic craft trying to circumvent – to find a way beyond our defenses or, failing that, simply drag his readers along with him into that strange, carefree new world, a world with which Capon seemed startlingly familiar. This dragging headlong into the outrage of grace especially describes the Capon of Between Noon and Three, which he described as his favorite experience as an author and his most important work.

He always tempered his seriousness with humor, his earnestness with playfulness, and always insisted theology should be nothing more than an interesting conversation topic on a walk in the woods. But despite his almost-always winsome tone and his irrepressible refusal to take himself too seriously, he possessed what Kierkegaard might have called a strong dialectical sensibility; that is, a willingness to put ideas in tension and pursue them to their furthest extent. This ‘dialectical’ style doesn’t only mean keeping proper distinctions between Law and Gospel and refusing any admixture, but also it means continually testing his theology against human experience and allowing the two to play off each other, unsettle and discomfit each other – in other words, his theological acumen combined with brilliant insight into human nature, his love of God with an earthy joie de vivre, in a way that lent constant movement, dynamism, and animation to his writing and thought.

He always tempered his seriousness with humor, his earnestness with playfulness, and always insisted theology should be nothing more than an interesting conversation topic on a walk in the woods. But despite his almost-always winsome tone and his irrepressible refusal to take himself too seriously, he possessed what Kierkegaard might have called a strong dialectical sensibility; that is, a willingness to put ideas in tension and pursue them to their furthest extent. This ‘dialectical’ style doesn’t only mean keeping proper distinctions between Law and Gospel and refusing any admixture, but also it means continually testing his theology against human experience and allowing the two to play off each other, unsettle and discomfit each other – in other words, his theological acumen combined with brilliant insight into human nature, his love of God with an earthy joie de vivre, in a way that lent constant movement, dynamism, and animation to his writing and thought.

Nowhere do we see exactly this aspect of Capon’s genius on display as it is in Between Noon and Three, a book we’ve reviewed before but, alas, the review left little room to explore any of Between Noon and Three‘s valences in any detail. One of the book’s most distinctive elements is Capon’s view of Atonement and reconciliation, a view not wholly his own (he’s drawing from deep, though often-overlooked, currents in the tradition), but no one can quite articulate it as he can. An almost Socratic humility and willingness to push on and test each new conclusion he comes to, in a way almost epektastic, never resting with confidence in one idea but always open to new articulations and unfolding of God’s love. All that by way of long-winded intro; I’ll try to trace, in outline, Capon’s atonement unfolding over about forty pages, near the book’s close:

I began, as most Christians do, with the image of Christ’s death on the cross as a sacrifice: Jesus the Great High Priest offers up to God his death as the Saving Victim and thereby makes a perfect satisfaction for the sins of the world. But for a number of reasons, I found this image less than satisfactory…it sounds awfully like a merely divine transaction: God doesn’t really help us out that much; the Trinity simply fixes up its internal relationships so the Father isn’t mad at us anymore. [And] when I came to take seriously the idea that all times and places, however unreconciled in themselves, are held eternally in God, all I could come up with was either a very large hell (which is, admittedly, one of the images of Scripture – but that large?) or a very unsatisfactory heaven, full of unrelieved agony.

Many writers would critique the satisfaction theory on the basis of over-differentiating the Trinitarian Persons at the expense of neglecting their common substance and co-operation, or something like that; but Capon allows his theology to be personal, a hermeneutic full of the dynamism of a living person while keeping just enough Scriptural and dogmatic checks in place to keep himself from going too far off the beaten path. To hear language like his is immensely refreshing; his approach just seems so alive. Continuing, Capon fastens on a new image to address some of the problems he found with the first:

Consequently, I found myself casting about for some imagery that would either shrink hell to reasonable theological proportions (thus allowing the divine Success to look a little less like cosmic failure); or, alternatively, cleaning up the New Jerusalem so it wouldn’t look so much like the South Bronx. What came to hand was the image of the dead human mind of Jesus between the time of his death and the day of his resurrection.

I struck me that if you took the utter of that mind… and posited the sheer oblivion of that mind as an eternal fact, you came up with a kind of universal black hole down which all the unreconciled evil of the world could be dumped. God says he will remember our iniquities no more; the dead human mind of Christ seemed to provide a way for omniscience to do just that: Jesus takes all the badness down into the forgettery of his death and offers to the Father only what is held in the memory of his resurrection. Christ as eternally dead (if he was dead even ten minutes, those ten minutes are still held eternally) provides you with someplace to put evil – with a hell inside Christ’s human death, so to speak. And correspondingly, Christ as eternally risen provides you with a ‘place’ for heaven: heaven is the actual, historical world that he offers, eternally reconciled, to the Father… all the unspeakable things go unspoken at the picnic by the Word who in the resurrection speaks them only to himself, in his death.

Okay, so now we’re getting into admittedly weird territory. But Capon’s mercifully un-self-conscious ability to follow the idea is at worst a fascinating look into an unusually insightful mind; at best it’s a way of thinking through both theology and our own experiences of evil, desire for restoration, etc, etc. Though theology, again, for him is never more than a porch – an entry into the house, but nowhere you should try to live. It’s this humility, in fact, that allows him to be so un-self-conscious and playful; it recalls some of the early Church Fathers who had no trouble whatsoever with saying weird things, because they were placing themselves in an adulating dialogue with something much bigger than them – in contrast to the more post-Enlightenment method of having to nail everything down, wrangle theological or biblical meaning into some neat and exhaustive paradigm (Catherine Pickstock seems to hate Peter Ramus for just this reason – and her sense of woe-is-the-modern-age protest against our need to ‘spatialize’ knowledge is strangely charming). But Capon doesn’t quite rest in this new model, either, because simple oblivion of sins, for Capon, may not adequately incorporate the whole of him in reconciliation:

There’s just too much of me that is eternally unmentionable. My sins are not appendages that can be lopped off and dropped into silence; they were, and are, me in action. Indeed, properly speaking, my problem is not my sins at all but my whole centerless life, my corrupted way of being that the Bible calls Sin – a condition from which not one shred of my history is exempt, except in Christ. If he’s going to tidy up the universe by dropping Sin into the divine forgettery, I’m going to have to go down there with it. All of me, not just chunks… Accordingly, I began to look for new clues….

[A]ll things arise out of nothing for one reason only: because of the desire of the Word and Spirit to offer to the Father what he delights to know… Since it is the very creatures themselves that are the gifts of the Beloved to the Father, the creatures themselves are participants by knowing themselves on whatever level they can manage. The apples of his eye, to whatever degree they can know and love themselves as apples, to that degree they really do participate in the knowledge and love of a Son for a Father who is crazy about apples.

In other words, the proper self-knowledge and self-love of every creates thing is ipso facto a participation in the knowledge and love of God. The entire universe moves by desire for the Highest Good simply because every part of it loves what God loves – namely, his own, unique being… Even those acts of knowledge that end up desiring what God does not desire had to be seen as expressions of the Highest Good by means of a desire to know what God knows. Perverted desirings, perhaps… but still that same desire to know which is the root of all motion and which, despite its perversion, is still a desire for the Highest Good.

Again, we see Capon’s experience (and knowledge of himself as sinner/apple!) in-forming his theology, and vice versa. Still strange, perhaps – but we’ve reached traces of Augustine and Gregory of Nyssa, Aquinas and Dante, but again Capon has the freedom to play around with these strands, appropriating them as he’s led. And regardless of how we evaluate his theology here, it’s a joy to follow him as he moves from one thing to another, because there’s so much honesty and personality there. And now Capon begins to reach something of a resting-place, as he moves into and then through the Christ and Adam (Rm 5) relation:

For if the origin of evil lay in the alteration of human [primarily self-] knowledge, then the end of evil – the quashing of it, the reconciliation of all its disastrous consequences – must somehow lies in a second alteration of that same human knowledge.

But that sent me straight back to the one available image of that second alteration: the human mind of the incarnate Word of God – the mind of Jesus, dead and risen. Only this time it offered itself not as a black hole down which vast sections of everybody’s historical existence had to be dropped into oblivion but as the device by which all the perverted alterations in human knowledge could finally be terminated and our full historical existence be seen as reconciled in the unaltered remembering that the Word of God offers to the Father. For our sake, Christ dies not simply to the law but to that whole contradictory way of knowing the good for which the law condemns us. By the deadness of his human mind and ours, we are literally absolved, set loose, from the unreconciled knowledge of our times as we held them in our hands. And in the power of his resurrection, we are lifted up into nothing less than the reconciled knowledge of those times as they are held by the Second Person of the Trinity in both his unaltered divine mind and his risen human consciousness….

[We] see it all with a knowing untainted by alteration, perversion, or contradiction (because the mind that knew it that way is dead forever); ad he grasps it no longer as the evil it once tried to be but as the desire for the Highest Good it always was in the offering of the Word to the Father. If our Fall was re-cognition, or re-knowing of the good as evil, then our Reconciliation is our re-cognition in Christ – our re-knowing in the risen humanity of the Word – of evil as the good he made it once more...

All the betrayals, all the missing of each other’s meaning: “…that is not what I had in mind at all” – down to the last betrayal, totally unnecessary and utterly inexorable, by which the light died and grace left their world. Of all that they must make anamnesis [recollection] if they are to re-enter the City of their love as Christ holds it for them. The years of dead light and absent grace must be recognized [re-cognized] as the only thing they can possibly be in Christ: Glorious Scars, the wounds of the alteration of their knowledge held forever by the re-collection by which grace gathers the dead into life.

But perhaps we have to keep in mind that this metaphor, or model, for Atonement is no more exhaustive or exclusive than any other, and our descriptions of the Atonement are never more than that, trying to put in writing the ineffable, though they may participate in truth to varying degrees. To my mind, Capon’s view is something we could use more of, though it’s by no means the final word. And so, with trademark humility, Capon closes the section:

At the end of the game of images, we put the cards back in the box and go to bed with nothing but the trust we started with… Another hand of cards, perhaps, in the morning; but through the dark times, only faith.

COMMENTS

10 responses to “Robert Farrar Capon on Self-Knowledge and Atonement”

Leave a Reply

Best party game cameo ever.

Ah, another Capon post from Mockingbird!

Finding it a few days ago was a double delight.

One: I’ve been rereading Capon the last weeks, and am intending to go back and ponder those chapters of The Youngest Day on atonement. I posted on Capon myself this week (Romancing the Word and Hunting the Fox).

Two: you have a picture of van Eyck, one of my favourite painters. The day before reading your post I started “Stealing the Mystic Lamb: the true story of the world’s most coveted masterpiece” by Noah Charney – apparently the Ghent Altarpiece in which it is found is the most stolen artwork in history!

It strikes me as an appropriate painting for Capon, who said he was accused of finishing many of his books in the same way: with the Marriage Supper of the Lamb – and in the background van Eyck has painted the turrets and spires of the New Jerusalem!