Here in Atlanta, pastor Andy Stanley often tells the story of a couple in his church whose newborn baby was dropped on its head by their obstetrician who was drunk when he delivered the baby. Several years later, the child has severe and permanent brain damage, but the couple has very publicly forgiven the doctor and reconciled with him. It really is quite a testament to the “absorption” that is necessary to move forward in some semblance of a friendship with someone who has wronged you horribly. To forgive like this is to take the emotions of anger, horror, incredulity, and vengeance and do something counter-intuitive with them. Instead of lashing out at the source of these emotions, forgiveness lashes inward, taking on (absorbing) the full weight of the guilt of the offending party.

Here in Atlanta, pastor Andy Stanley often tells the story of a couple in his church whose newborn baby was dropped on its head by their obstetrician who was drunk when he delivered the baby. Several years later, the child has severe and permanent brain damage, but the couple has very publicly forgiven the doctor and reconciled with him. It really is quite a testament to the “absorption” that is necessary to move forward in some semblance of a friendship with someone who has wronged you horribly. To forgive like this is to take the emotions of anger, horror, incredulity, and vengeance and do something counter-intuitive with them. Instead of lashing out at the source of these emotions, forgiveness lashes inward, taking on (absorbing) the full weight of the guilt of the offending party.

Such a gesture seems otherworldly, even to those of us who think we have a decent understanding of what it might look like to forgive like God does. Some of us observe this and think, “I just hope that I could respond with that kind of grace and forgiveness if I were ever in a situation like that”. Others may feel more of a disconnect with this scenario, “though I fully see this as a picture of God’s forgiveness, I don’t believe that I could extend it to that level, it would just be too hard”.

Jon Dorenbos admits as much. When the Philadelphia Eagle’s Pro Bowl long-snapper was 12, his otherwise mild-mannered father bludgeoned his mother to death in a fit of rage. Dorenbos and his older sister went to live with an aunt, where Dorenbos took up magic as a hobby he could pour himself into in a way that helped distract him from the aftermath of the tragic event. His story was given a spotlight in a segment this week on HBO’s Real Sports. Long-snappers in the NFL typically toil in anonymity, but Dorenbos is a celebrity in Phildelphia. His talent for magic and his demonstrative, good-natured presence (combined with his tragic backstory) have garnered him a strong following.

In the segment, Bryant Gumbel asked Dorenbos if he has forgiven his father (who has recently been released from prison). Dorenbos responded, “I have come to a place where I have been able to forgive him, and I’ve moved on with my life”. Gumbel followed up, “have you had contact with him?, and do you have any desire to see him or speak to him”? Dorenbos, “no”. I found myself startled by my initial reaction to Dorenbos’s response. My thought was, “Come on man, it was a fit of rage, your father has paid for what he has done, and you won’t even talk to him? That’s gonna tear you up inside, dude!” It’s as if I somehow know (because I’ve witnessed what supposed “real forgiveness” looks like) what’s going on inside of him and how he can most “effectively” deal with it.

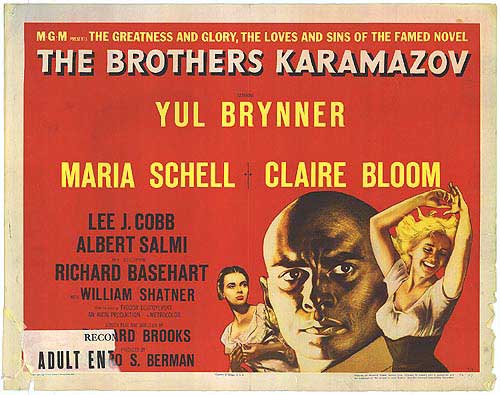

Processing pain and tragedy is difficult and complex, and we process them according to how our vastly different experiences and identities tell us to. Still, I find myself projecting onto other situations how I think forgiveness should go, and how others should do it. I tend to expect people to communicate their “perspective” on pain and suffering with all of the eloquence of Dostoevsky’s Ivan Karamazov:

I believe that suffering will be healed and made up for, that in the world’s finality, at the moment of eternal harmony, something so precious will come to pass that it will suffice for all hearts, for the comforting of all resentments, for the atonement of all the crimes of humanity, of all the blood that’s been shed, that it will make it not just possible to forgive, but to justify all that’s happened. – Brothers Karamazov

I do believe this is true. I have to believe that this is how it’s going to work – it seems the best answer and best hope for what “I make all things new” (Revelation 21) is going to look like. However, I’ve never been through what those parents with the injured baby have been through, or what Jon Dorenbos has been through. If it were me, if I’m honest, my very imperfect ability to forgive would likely reside somewhere between non-existent and “Lord, I do believe, help me in my unbelief” (Mark 9:24).

COMMENTS

8 responses to “When Forgiveness Also Says “I Never Want to See You or Speak to You Again””

Leave a Reply

Sometimes forgiveness of a great wrong or betrayal is just giving up what feels like your right to punish the offending party; if your decision to move on with your life without much or any contact with the person who wronged you is not about trying to punish but more about peace, I think it can be a gracious way to proceed.

You are also assuming that the party requiring forgiveness has amended or corrected their wrong behavior. It is possible to forgive even when your obstetrician is still a drunk or father still struggles with rage. That, in my experience, is where true forgiveness lies. Forgiving even when the offending party has not asked for it. That is the difference between reconciliation and restoration. Reconciliation can be a one way act of forgiveness but true restoration can only occur when both parties pursue it, addressing the wrong or hurtful behavior with the intention that it does not happen again.

Thanks for the comments. I wanted to convey here that we (or at least I) tend to project onto other people (unfairly) how we think they should forgive – based on the awesome acts of forgiveness that have been presented and modeled to us. As both of you point out, forgiveness is far too nuanced for us make inferences about how well/poorly others have gone through the process of forgiving.

This is really good. Thanks for posting.

I always think about forgiveness as having a vertical and a horizontal dimension. The vertical dimension is the starting point, and the really crucial one: giving up to God the desire for retribution, acknowledging that He’s in charge of justice and mercy. It sounds like both of these examples show this dimension of forgiveness. The horizontal dimension has to do with restoring the interpersonal relationship. This can’t always happen, whether because the pain is too deep, the person to be forgiven is absent or dead, or there’s reason to believe that the person to be forgiven is likely to reoffend (no remorse or repentance). The couple with the injured baby is a heroic example of extending forgiveness in the horizontal dimension, but I’m not going to say that forgiveness without restoration of the relationship is defective. It’s still forgiveness.

I had a “friend” sleep with my ex-husband, and then she stalked me for years. I could write a book with all the psycho stuff she did. Finally there was a mediated session with her, and what she wanted was to know that she was forgiven. I had been telling her that she was forgiven for years, but her own self-unforgiveness consumed her. When I looked her in the eye & told her “Yes, I have forgiven you,” she was visibly relieved. I thought we could end it there, but then she asked one of the mediators if she could ask another question. Her question was “Can we be friends?” Thankfully, the mediator saw the bigger picture and told her No, it was best to forgive and move on, and it would be better if we were not in each other’s lives. He told me later that he didn’t think her behavior had changed, and we would be back in the same spot in a year. Sometimes, forgiveness without restoration is really a good option. Forgiveness does not have to include restoration (what if you are forgiving the dead parent who abused you, etc?). Forgiveness is releasing your hurts to The Lord and walking in the freedom given to me in exchange for my wounds.

To quote Lewis B. Smedes: ‘To forgive is to set a prisoner free and discover that the prisoner was you.’

I’m reminded of Professor Craig Koester who in my class stated it this way (my paraphrase):

“Forgiveness is making the choice in a relationship that your past with someone will no longer determine how you relate to them in the future.”

At times, this can take quite an extra-ordinary form, with all the big example stories of forgiveness we hear about, where there is newness and freedom. Other times (as I’m personally just learning and having my own assumptions challenged!), that new future in our creatureness may not be able to handle restoration — we just end up playing Weekend at Bernie’s, trying to get life out of a corpse. In those cases we need full on resurrection! And that just may be only on the other side of grace, the end of the simul…

One doesn’t have to forgive and it doesn’t mean you live with hatred in your heart either. It means erasing the significance of that person’s existence in your life. I don’t forgive my ex husband for his wrongdoings and I don’t feel bad about it. I’m not consumed with issues of revenge. He’s just become a non-issue in my life going forward. He no longer exists for me and that’s good enough for me without having to forgive anything.