Have you ever called in sick for work and gone to the movies instead? How about dishing some dirt on a coworker in order to edge them out for a promotion? While these kinds of offenses may have seemed shady in the past, we seem to be growing more comfortable with this kind of behavior. One side-effect to working remotely is that we’re not as attached to our co-workers as we used to be. We may enjoy being able to check social media during a Zoom meeting, but doing so comes with a cost.

This is what Jerry Useem is pointing to in his recent Atlantic article, “The End of Trust.” Even though the economy has mostly bounced back from the early-pandemic recession, a more mysterious commodity is on the decline: our ability to rely on each other. Now, more than ever, supervisors distrust their remote workers, coworkers lack any personal connection with each other and employees are second-guessing the tone of their boss’s emails.

Useem backs up these cultural shifts with economic studies, citing that employee-surveillance software has risen 50 percent since 2019 and American employees are leaving their jobs at a higher rate since the dawn of the century. According to a study of more than 5,400 Finnish workers, the degree of trust people had in each other experienced a steep decline during the pandemic due to lack of personal interaction. Similarly, in America, the underlying reason why only 30 percent of Americans believe that most people can be trusted is due to lack of physical contact.

In such a hyper-individualized world in which convenience reigns supreme, the issue of trust may sound like a moot point. Similar to more ethereal essentials like humor or hope, trust is one of those things that can often take a backseat to other concrete necessities like groceries or rent. But the erosion of trust is bound to affect us in real ways, Useem says, because it’s actually a money issue. “Trust is to capitalism what alcohol is to wedding receptions: a social lubricant,” he writes, arguing that a country’s GDP depends on people collaborating with and depending on each other. We may care more about the loss of societal trust if it hits our wallets, but the relational setbacks are just as important.

What has suffered most during the pandemic are “weak ties” — the friends of friends, the neighbor down the street, the old ladies at church. Small talk may sound cheap, but the casual interactions we have at the post office or the check-out line are what tells us that we are a part of something much more significant than ourselves. We need the “nice day, isn’t its” and the “take care nows” to remind us that complete strangers are, in fact, as important as we are. Having been starved of this public interplay for two years, Useem suggests that an irreversible trust spiral has begun.

As Christians, we are no different. We, too, fall prey to “mortal pride and earthly glory. Sword and crown betray our trust.” But the Christian faith stands in stark contrast to our human tendencies in that is built entirely on trust. Take the bodily resurrection of Christ, for instance. Some may attempt to unearth the chronicled artifacts of the risen Christ in order to help prove his historicity, but the Easter narrative resists the historian’s quest for unadulterated certainty. Those who insist on seeing things for themselves find themselves in a blind alley. “Is the trustworthiness of the first witnesses sufficient? Can we really stake our lives based on what others have told us?” they ask. The Apostle Paul claims precisely that, reassuring the Corinthians that the risen Jesus appeared to hundreds of witnesses, many of whom were still alive. Not only was his own account of encountering Jesus worthy of trust, but so were the accounts of those who Paul himself had trusted. Paul wanted the Corinthians to know that the good news on which he stood was solid ground. The Corinthians could question his validity all they like, but the miracle of belief eventually all comes down to a surrender of certainty.

The ultimate question of trust becomes not “can we trust God?” but “where else shall we turn?” In the end, the only alternative for trusting someone else is trusting oneself and it’s only a matter of time until that option loses its appeal. Recalling Megan O’Gieblyn’s critique of holding our neighbors accountable via doorbell cameras, “we should not presuppose that we are our best selves, that our motives are entirely pure,” but, rather, “practice a vigilant self-doubt.” In other words, the antidote to mistrust of others is a radical mistrust of oneself. If we know ourselves to be undependable and prone to misjudgment, we may be more willing to risk taking others at their word.

Alongside self-doubt there is the vulnerability of love that imputes to others the best possible motives. Rather than assuming that the cashier was trying to overcharge you, what if we concluded that they were simply tired from a double shift? In other words, to refrain from thinking that other people are trying to pull one over on us is to live by faith. Who knows? Perhaps other people might actually be right.

Even more radically, why not be wronged? What is love if not the act of entrusting oneself to others even at great personal cost, even if they are thieves and robbers? As troubling as Useem’s diagnosis is, it sounds similar to Jesus’ own take on humanity. Jesus never advocated for people to trust one another “for he himself knew what was in everyone” (Jn 2:25). He instructs his disciples to be shrewd as snakes, knowing full well that people are not exactly dependable nor upright. And yet, knowing what people are capable of didn’t stop him from putting his own life in their hands. Jesus willingly took on the risk of trusting others. And where exactly did that get him? Depending on how you look at it, it either got him into loads of trouble and/or it led to the salvation of the world.

In an age where we are told to trust no one and to question everything, Christianity can be a place where our sneaking suspicions are not answered with evidence, but cut down at the knees. It is the singularly unique place where we are held by a truth that is far more vast than we could ever fathom. Our world may be experiencing an irreversible trust spiral, but Jesus has proven himself capable of calming our storms of doubt.

In the end, trust is much closer to a last resort than a rational decision. It is not signing on a dotted line as much as it is surrendering your own grip and falling into another’s embrace. We may waver and speculate all we like, but we may eventually realize that there is little else to hold onto.

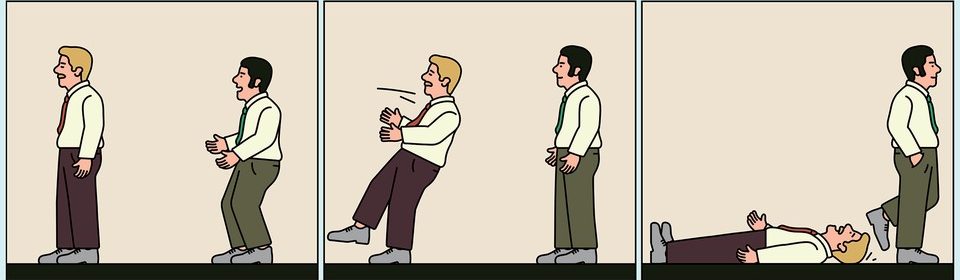

Think of the age-old ritual of the work retreat: the trust fall. Your coworker stands behind you and vouches to catch you as you allow your feet to give way. It is a manifestation of the trust we put in each other day in and day out. Sometimes you may fall to the ground and, surprisingly, it isn’t nearly as cataclysmic as you had feared. Other times, you’ll be caught. Still, it’s far better to risk falling to the floor than to stand alone.

COMMENTS

2 responses to “Trust No One and Question Everything”

Leave a Reply

[…] article at the website Mockingbird extends this trust deficit to the world beyond the workplace, noting that during the pandemic one […]

This was an interesting entry for me to read in light of a conversation with a non-American friend who has been visiting the States. He said one thing that really stood out to him was the number of times Americans warned him about his personal safety or told him to arm himself while he was out and about here and “trust no one.” It made me think about how personal safety and issues of trust are ingrained into messages of our era of American childhood. Another thing he pointed out was how those messages often seemed to be tied up with deep-seated prejudice and inaccurate perceptions of ‘the other.’ This is all really making me think. Thanks for sharing your thoughts, Sam!