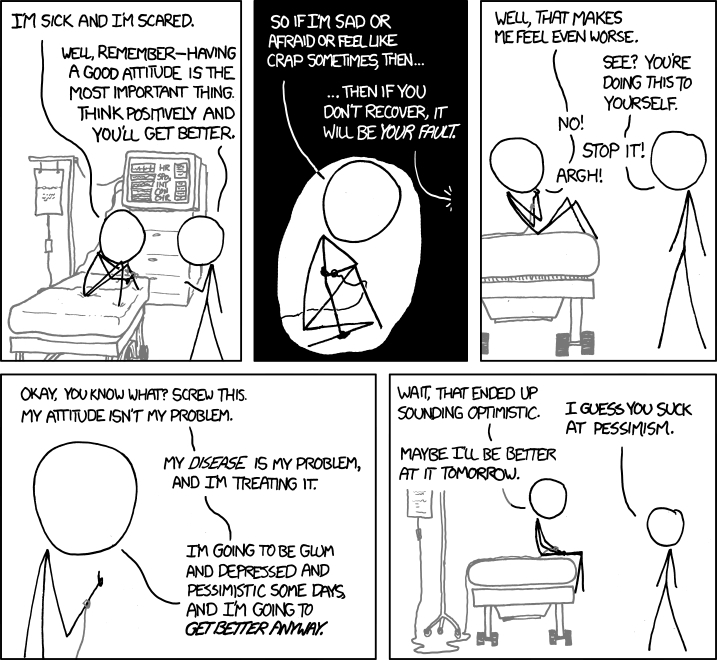

Where does the American dream end and the Christian Gospel begin? Admittedly, not a question often explored in The NY Times Book Review. That is, until Hanna Rosin wrote up Barbara Ehrenreich’s new forcefully-titled Bright-Sided: How Positive Thinking Is Undermining America. The book was inspired by Ehrenreich’s own bout with breast cancer, and it would seem that her investigations led her straight to… the church. Sadly, the message she heard there appears to have been very similar to the messages she found on hospital greeting cards and in management seminars, bearing little to no resemblance to that of the Suffering Servant. One can hardly blame her for picking up on the troubling flipside of prosperity theology, i.e. that it basically blames the patient/victim for their sickness/trauma (John 9, anyone?), causing believers to endlessly second-guess their faith, or give it up altogether when the going doesn’t get any less tough (or they prove unequal to the task). The initial attraction of the message, while certainly understandable, ultimately contains only a passing affinity to genuine hope, or reality. Some might say it even compounds the suffering in question, short-circuiting prayer and keeping the Great Physician at bay – to the extent that that’s possible.

So at the risk of sounding like a party-pooper, this kind of stuff is more than an easy target of misguidedness, it’s cruel! Especially when something like cancer is involved… Rosin wisely takes things a step further than Ehrenreich, observing that the bootstraps mentality goes far deeper than the promise of financial stability – it is grounded in the elusive dream of existential autonomy, i.e. original sin. As such, none of us are immune; we are all in need of a good Word, are we not? Maybe even a positive one, ht VH:

All the background noise of America — motivational speakers, positive prayer, the new Journal of Happiness Studies — these are not the markers of happy, well-adjusted psyches uncorrupted by irony, as I have always been led to believe. Instead, Ehrenreich argues convincingly that they are the symptoms of a noxious virus infecting all corners of American life that goes by the name “positive thinking.”

What started as a 19th-century response to dour Calvinism has, over the years, turned equally oppressive, Ehrenreich writes. Stacks of best sellers equate corporate success with a positive attitude. Flimsy medical research claims that cheerfulness can improve the immune system. In a growing number of American churches, confessions of poverty or distress amount to heresy. America’s can-do optimism has hardened into a suffocating culture of positivity that bears little relation to genuine hope or happiness.

Ehrenreich’s inspiration for “Bright-Sided” came from her year of dealing with breast cancer. From her first waiting room experience in 2000 she was choking on pink ribbons and other “bits of cuteness and sentimentality” — teddy bears, goofy top-10 lists, cheesy poetry accented with pink roses. The sticky cheerfulness extended to support groups, where expressions of dread or outrage were treated as emotional blocks. “The appropriate attitude,” she quickly realized, was “upbeat and even eagerly acquisitive.” The word “victim” was taboo. Lance Armstrong was quoted as saying that “cancer was the best thing that ever happened to me,” while another survivor described the disease as “your connection to the divine.” As a test, Ehrenreich herself posted a message on a cancer support site under the title “Angry,” complaining about the effects of chemotherapy, “recalcitrant insurance companies” and “sappy pink ribbons.” “Suzy” wrote in to take issue with her “bad attitude” and warned that “it’s not going to help you in the least.” “Kitty” urged her to “run, not walk, to some counseling.”

The experience led her to seek out other arenas in American life where an insistence on positive thinking had taken its toll. One of the more interesting chapters concerns American business culture. Since the publication of Dale Carnegie’s “How to Win Friends and Influence People” in 1936, motivational speaking has become so ubiquitous that we’ve forgotten a world without it. In seminars, employees are led in mass chants that would make Chairman Mao proud: “I feel healthy, I feel happy, I feel terrific!” Corporate managers transformed from coolheaded professionals into mystical gurus and quasi celebrities “enamored of intuition, snap judgments and hunches.” Corporate America began to look like one giant ashram, with “vision quests,” “tribal storytelling” and “deep listening” all now common staples of corporate retreats.

This mystical positivity seeped into the American megachurches, as celebrity pastors became motivational speakers in robes. In one of the great untold stories of American religion, the proto-Calvinist Christian right — with its emphasis on sin and self-discipline — has lately been replaced by a stitched-together faith known as “prosperity gospel,” which holds that God wants believers to be rich.

“Where is the Christianity in all of this?” Ehrenreich asks. “Where is the demand for humility and sacrificial love for others? Where in particular is the Jesus who said, ‘If a man sue you at law and take your coat, let him have your cloak also?’ ” Ehrenreich is right, of course, in her theological critique. But she misses a chance to dig deeper. I have spent some time in prosperity churches, and as Milmon F. Harrison points out in “Righteous Riches,” his study of one such church, this brand of faith cannot be explained away as manipulation by greedy, thieving preachers. Millions of Americans — not just C.E.O.’s and megapastors but middle-class and even poor people — feel truly empowered by the notion that through the strength of their own minds alone they can change their circumstances. This may be delusional and infuriating. But it is also a kind of radical self-reliance that is deeply and unchangeably American.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K0eDpsROSvQ&w=600]

COMMENTS

6 responses to “Choking on Pink Ribbons: Barbara Ehrenreich on Calvinism, Megachurches and Positive Thinking”

Leave a Reply

I'm maybe gonna catch a little heat for this, but this is a hobby-horse (hopefully not a high one) for me: radical self-reliance is NOT American. It's human. It is very easy for us (paradoxically) to point the finger at ourselves, pining for the superficial cultural differences of "the other." Remember, though, that it was a first century Jew (not a 21st century American) who asked Jesus, "What must I do to be saved?"

This really does look like an interesting book. An interesting part of the Calvinism part is the "Protestant work ethic" we all learned about in business school.

You know you are one of the elect if you are living a holy life and you are successful. Fascinating tie-in with Calvinism and the prosperity gospel.

Someone once told me that Puritan are only good reading if they are either in prison or near death. All the trivial nonsense gets cast away.

I should say, for the record, that I completely agree with Ehrenreich about superficial positivity undermining us…if The Secret was so possible, what's stopping us? Thetans?

I don't know…I wonder if Wesley and the huge Arminian/Revivalist influence of the 19th century played a bigger role in shaping today's American religious landscape. The heirs of the Puritans were all Unitarians by the Revolutionary War.

Of course it's Thetans, Nick. Duh.

I don't think I am giving you heat about the whole cultural vs. universal locus of sunny you-can-do-it optimism. You're right that it is in one sense universal.

But every culture in every age latches on to certain aspects of human sin and exacerbates them further. (Each having its own besetting weaknesses.) So I don't think it's actually a conflict to say that the problem of "reliance on self" is both universal and also made that much worse by America's own distinctive national mythology — it's culture.

We can see this sort of thing in Christian communities. The desire to "pole vault over Calvary on the way to Pentecost" (for example) is universal. But it's also an especially besetting weakness of Pentecostal churches. The culture of that communities makes it much easier to fall into that.

And of course each culture and every church in fact has its own besetting cultural weaknesses.

It's the damn Americans, no, it's the damn Calvinists, no, it's the damn Pentecostals, no, it's the damn Calvinist Puritan American Pentecostals. All I know for sure is it's them, them, them.