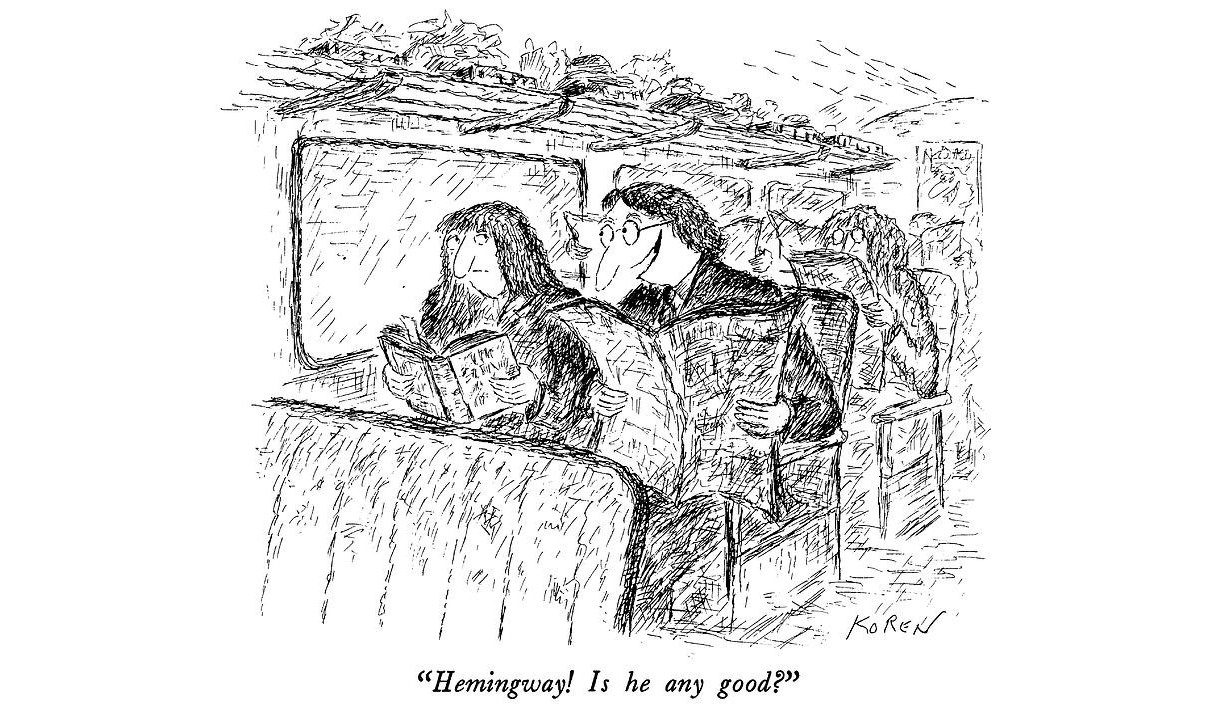

Every bookworm knows the rule: don’t roll your eyes at mispronunciation of big words or foreign names; the speaker is probably a voracious reader who learned the term not from speech but from the page. For instance, growing up I thought segue was spelled “segway,” like the scooter. When I saw the word in writing I mentally rhymed it with league, having no idea what it meant.

I don’t recall who set me straight on that one, but I’m forever grateful to my boss at the library where I worked during seminary. Barth, Rahner, and Schleiermacher no longer twitch in their graves when I say their names. I now try to recall this blessed ignorance when my students rhyme “Barth” with hearth, or when they give me funny looks when I refer to “Saint Augustine,” with emphasis apparently on the wrong syllable. Isn’t he the one the grass is named for?

I’d like to propose an analogue to the bookworm rule: don’t roll your eyes at personalized lists of Important Books to read in a year, or earnest admissions of having read and enjoyed Wrong Authors. The reason is simple: everyone has to begin somewhere. Someone ignorant of the classics is wise to begin there, with canonical titles she’s heard countless times but never tried for herself. Whether the titles thus heard are in fact classics is one of the things that, by definition, she cannot know in advance of reading them.

With literature, the only way to make a judgment about quality is by developing it through continuous exposure to, well, all of it — the good, the bad, and the middling. Criticizing an ill-read person’s unwitting plan to take up Ayn Rand, given how many times he’s seen her name pop up over the years, is an exercise in missing the point. Not only could our enterprising upstart not know Rand is bad before reading her, but spending time with her may well be the start of a search for beauty, not having found it in the dim dungeons of objectivism.

A few years ago there was a minor dustup on a popular website devoted to destroying basic literacy and love for reading — I refer to the suitably renamed “X” — in response to a post that outlined some New Year’s reading goals. It included one “classic” every few weeks, and besides Greek philosophers and standard-issue Great American Novels there were newer books like Sapiens and Homo Deus by Yuval Noah Harari. Pile-ons ensued, everyone clarified their own status as not a chump, and alternative lists abounded.

It’s true that Harari is an outlier on a list with Aristotle, Augustine, and Nietzsche. So what? It’s bizarre to put down an attempt at self-education before it’s begun. That’s what this was, after all: an attempt by an adult, probably approaching middle age, to fill in gaps in his education. There’s something honorable in that. At least I hope so. I’m a tenured professor with a passel of degrees, I turn forty later this year, and I’m still filling in the gaps. I’m ashamed to admit there are a lot of them.

Should I feel ashamed? I’m the product of an above-average American public school system. (The faint praise is damning, I’m aware.) I grew up upper-middle class and read more than most of my teenage peers. My parents required a minimum of nightly reading for me and my brothers: a steady diet of Bible and fiction. I certainly didn’t know any other kids reading Kierkegaard and Bonhoeffer in high school.

Yet now when I compare what I’d read by age twenty or thirty with colleagues or, God forbid, with scholars from the past, I’m embarrassed into silence. It would be only a slight exaggeration to say that, from elementary school through college and into graduate school, my teachers studiously avoided assigning me any readings from the Western canon. No Homer or Virgil. No Tacitus or Seneca. No Milton, Cervantes, Goethe, Austen, Melville, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Chekhov, Proust, or Mann. One Shakespeare (The Merchant of Venice), maybe two (Romeo and Juliet). One Dickens (A Tale of Two Cities). One-third of Dante (you know which part). No Eliot or Auden or Rilke or any other poetry I can remember. Someone required The Stranger; another, The Scarlet Letter. I was introduced to Holden Caulfield and Boo Radley, Hester Prynne and Tess Durbeyfield. The rest I never met.

Indeed, the only reason I happened to have read a few theologians before college was because a youth minister put them in my hands. Had I not gone on to earn a succession of degrees in theology, I would never have been exposed to Plato, Aristotle, Augustine, Thomas, Luther, Calvin, Locke, Kant, Hegel, Newman, and the rest. Had I earned a degree in business or nursing and not been enrolled in the Honors College (something of an accident; I’d never before heard of “great books”) I would have entered the workforce at twenty-two and lived my life blessedly ignorant of nearly every major writer and thinker in human history. And I was a natural reader interested in ideas and culture. What if I wasn’t?

I don’t deny that this is one more indictment of our educational institutions and their decline, at every level, from generations past. My interest, though, is elsewhere. I have one eye on my academic cohort and the other on my students.

Start with the latter. The situation is worse for Gen Z than it was for my generation. They don’t know a world without tablets, smartphones, or social media. Many of them have been on Instagram since middle school. BookTok notwithstanding, TikTok might have been designed in a lab with the precise aim of destroying the ability of young people — of anyone at all — to maintain the focus necessary for long stretches of uninterrupted reading.

Anecdotal experience in the classroom bears out the empirical data: the kids aren’t reading. I had one student who, prior to taking a class with me, had never read for pleasure, cover to cover, a novel written for adults. I challenged him to choose one during his semester with me and give it a shot. He did it. His first book! Not in middle school but in college.

As his teacher, I took it as a win. In the big picture, however, it’s a depressing sign of the times. And with the advent of A.I. and “artificial teaching assistants,” it’s only bound to get worse.

Back to my cohort. I’m far from the only one underserved by my education, at least in this respect. I had a friend in high school AP English who would plagiarize his book reports, only the content wouldn’t be about The Scarlet Letter; it would be about a completely unrelated subject, like the Pacific theater in World War II. He got the same grades as the rest of us. We learned then that our teacher wasn’t even reading our papers.

Hence my sympathy with the middle-aged Twitter autodidact. It wasn’t until my doctoral studies that I found time to finish Dante. I was already a professor when I assigned myself Milton. Just last year I read through Homer with a group of friends. A few years prior it was Melville and Mary Shelley. Before that it was Dostoevsky. One day I may even arrive at Proust. I will never forget an email I received just before moving away to start a PhD. My thesis advisor wrote to give me a single summer reading recommendation: Proust’s “À la recherche du temps perdu” — all of it, and preferably in the French. Had it been anyone else, I would have laughed. Not him. I knew he wasn’t kidding.

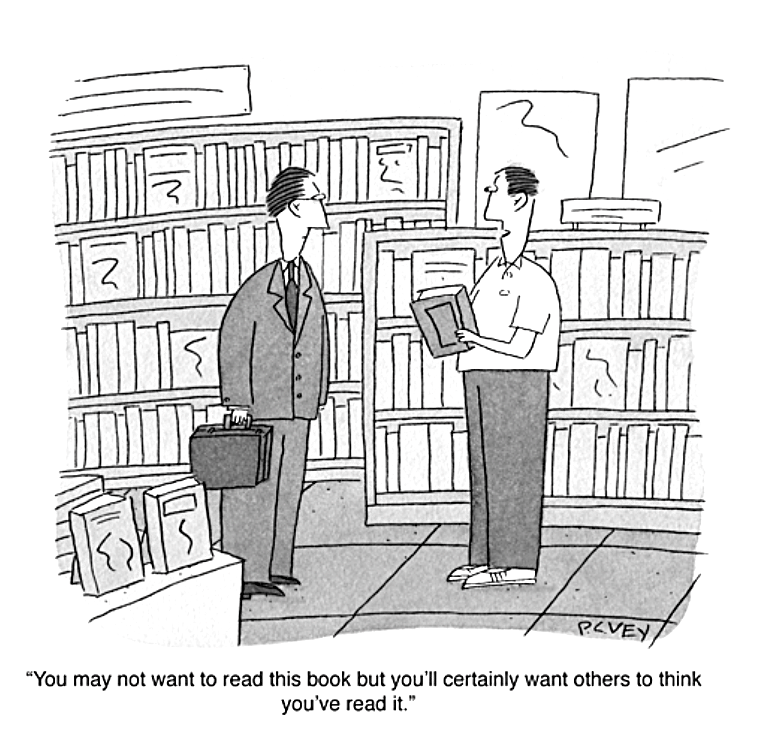

I try to tell myself it won’t take a lifetime to follow his advice. But the truth is that it might. Academics are already chronic victims of imposter syndrome. We all nod along at books we’ve not read and authors we’ve never heard of. My greatest fear is being found out at the exact wrong time: asked whether I’ve read X just when it’s next on the “make up” list. (Will God forgive me if I lie?) So the notion that one of the true classics might remain unread by me before I retire or die is almost too much to bear. Surely I can catch up by fifty?

No. I won’t. There is no catching up. There is always more. The list is never finished. One can either accept this or live in denial, but the possibility of having read everything worth reading vanished centuries ago. Perhaps it was always an illusion.

Even acknowledgement of the illusion can function to confirm it: a sort of literary humblebrag. In Cultural Amnesia, his global encyclopedia of every writer and statesman that mattered in the twentieth century, Clive James pauses at multiple points to assure the reader that there are, in fact, books he hasn’t read. Yet while it may score moral points for technical honesty, his claim that “this is avowedly a book by someone who has not read everything” mostly just induces jealousy. Yes, he has: the evidence is the book. Or so it seems to this resentful reader.

At any rate, I find not only that am I sympathetic with the aspiring autodidact. I find that I am one. And the two of us are not so distant from my illiterate student. None of us has read what we should or even what we wished. All of us need help. Lacking it, our bookish quest becomes a form of self-help. That’s what self-teaching is, in its own way: self-help via literature.

***

The predicament as I see it is threefold: schools, students, and former students (some of whom are teachers). Another way to put it is in terms of stages of reading, from learning it to handing it on to practicing it in one’s daily life as an adult.

Regarding the question of education, Clive James has the necessary strong medicine:

Readers my age were made to memorize and recite: their yawns of boredom were discounted. Younger readers have been spared such indignities. Who was lucky? Isn’t a form of teaching that avoids all prescription really a form of therapy? In a course called Classical Studies taught by teachers who possess scarcely a word of Latin or Greek, suffering is avoided, but isn’t it true that nothing is gained except the absence of suffering? In his best novel, White Noise, Don DeLillo made a running joke out of a professor of German history who could not read German. But the time has already arrived when such a joke does not register as funny. What have we gained, except a classroom in which no one need feel excluded?

True enough, if easier said than done. The same goes for my students, whose needs are not a mystery. In the language of Jonathan Haidt, they need play-based rather than screen-based childhoods. They need an adolescence without social media. And they need classrooms uncolonized by devices.

Unfortunately, outside of my own home and classroom, I can’t do much about these needs. My students can’t use laptops or tablets in my courses, but they can and do in others. It’s not nothing, but it’s unlikely to make a long-term difference. Facing down Silicon Valley, one reaches for the language of combat — say, bringing a knife to a gunfight. But the imagery is off. Say instead that resisting ed tech is like trying to illuminate a city with a single match.

It seems to me, then, that we should accept the inevitable, at least in the aggregate. The trends will persist, book reading will continue to decline, and most of an entire generation will enter adulthood functionally illiterate. From high school and college they will emerge somehow even more ignorant than I was of the classics of literature to which they should have been exposed by a basic education in the liberal arts.

***

Besides despair, blame and hand-wringing are common responses to this state of affairs. Let me suggest another. Gen Z isn’t responsible for the mass experiment conducted on them. It’s not their fault. They’re victims. Blame the adults, not the children. The children, for their part, aren’t a lost cause. When I look at twentysomethings on their phones, I see a mass of refugees hungry for knowledge, desperate for culture, and open — if not now, then later — to doing the hard work necessary to gain it.

In a word, this is a generation of autodidacts. For now, their instruction comes from YouTube and Reddit and Spotify. But these are points of entry, not ports of harbor. I can already tell in the classroom: they know that influencers are empty calories, at best a candy bar or bag of chips. They don’t satisfy. The nourishment is found elsewhere. And the best of the popularizers (they’re not all bad) point them there.

If, therefore, we should avoid cheap optimism about Gen Z, we should also resist the temptation to passivity. We have an opportunity, and it isn’t limited to the traditional years of K–12 schooling. There will always be an appetite for the classics. Nor is our situation utterly dissimilar from the past. I didn’t grow up with a smartphone, plus I’m an education lifer — I’ve been in the classroom since I was five — yet I’m still filling in the seemingly infinite gaps of my modest personal bibliography. I have plenty of friends in the same boat, and soon enough my students are going to find themselves in it too.

In the coming years they’re going to need two things: On one hand, a culture that honors and even incentivizes autodidacts; on the other, institutions that welcome and direct their desires, nurturing a love for learning and drawing readers together in their pursuit of the good, the true, and the beautiful. Consider The Catherine Project, for example. Founded in 2020 by Zena Hitz, it’s basically a great books seminar program for adults of all ages, minus grades, tuitions, and assignments. One doesn’t receive credits or a diploma, either, but this appears irrelevant to enrollment, which stands at six hundred a term.

We should not be surprised. And may their tribe increase. We need a thousand Catherine Projects to meet the need, not to say the demand. Who’s to say churches and parachurch ministries can’t be part of the solution? We Christians have a vested interest in the business of ordinary literacy.

In any case, the upshot should be clear. The next time you see a New Year’s list of classics leavened with rubbish, don’t laugh or pile on. Say an encouraging word. Point them to Professor Hitz. Better yet, start your own middle-aged book club for illiterates. I’ll be your sponsor. If it helps, I’ll be your patron saint.

Compelling! Thanks for the nudge. Having started I’ll finish Brideshead Revisited. At 87 it’s time.

Excellent article! Thank you.

What a great article. You’ve beautifully stated the problem and the solution, too. Thank you!

Really fantastic article. Thanks Brad!