As some of your own poets have said, “We are his offspring…”

– Acts 17:28

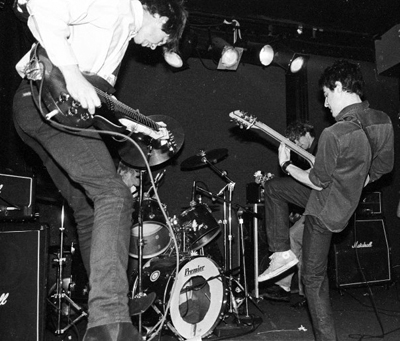

Concept albums typically belong to the realm of progressive rock made popular in the 70s by bands like The Who, Rush, Pink Floyd, etc. Even Parliament had albums that were thematic epics set to music. Along with Hüsker Dü’s Zen Arcade, Washington DC’s Rites of Spring utilized mid-80s post-punk to contextualize the journey of self-discovery. Before Guy Picciotto and Brendan Canty formed half of seminal indie band Fugazi, the short-lived Rites of Spring performed no more than 15 local shows, smashed countless guitars, and left stages strewn with flowers amid the aftermath of their chaotic, cathartic rants, which wove together themes of love, existential angst, and, more specifically, breaking up.

1985 was known as Revolution Summer in the highly influential DC music scene where the focal point in punk rock took a socially conscious turn. Bands abandoned the raw aggression of early-80s punk in favor of introspective lyrics and personal reflection. This is poignantly reflected in “Deeper Than Inside,” the second track on the band’s sole full-length album, End on End, as a drum roll ignites a frantically paced manifesto on the dedication to the inward journey. If Genesis 3:5 had a proto-emo, post-punk anthem, this would be it! This is pure law inasmuch as it’s a declarative-yet-implicit demand that we find ourselves, know ourselves, become ourselves through our own personal inner search. In signature raspy vocals, Picciotto exclaims,

I’m going down, going down, deeper than inside … and once inside, I’m gonna tear until there’s nothing left to find.

The track unknowingly invokes the book of Ecclesiastes as Picciotto parenthetically utters the refrain, “the world is my fuse.” Solomon predates Rites of Spring by several millennia as he declares,

I said to myself, “Come now, I will test you with pleasure to find out what is good.” But that also proved to be meaningless. “Laughter,” I said, “is madness. And what does pleasure accomplish?” … I denied myself nothing my eyes desired; I refused my heart no pleasure. My heart took delight in all my labor, and this was the reward for all my toil. Yet when I surveyed all that my hands had done and what I had toiled to achieve, everything was meaningless, a chasing after the wind; nothing was gained under the sun. (Ecclesiastes 2:1-11)

In fact, the structure of End on End loosely parallels that of the Teacher’s treatise on the futility of life, making this one of my favorite unintentionally gospel albums. Both begin with the acknowledgement that life is vain (1:2). Both proceed to document what we naturally do to self-atone and reconcile the tension between what we know should be versus what actually is (2:1-11). Both confirm that hedonism doesn’t satisfy (2:11, 15-23, 4:4, 7:23-29) yet validate the goodness of the law (12:13). Finally, both conclude the matter with either a word of law or a commitment to “do more, try harder” (12:13).

“Meaningless! Meaningless!” says the Teacher. Utterly meaningless! Everything is meaningless.” (1:2)

The Law judges us and finds us wanting, as the opening track “Spring” indicates in its apt depiction of the human condition under the curse:

Caught in time so far away from where our hearts really wanted to be

Reaching out to find a way to get back to where we were …

Caught at a distance with myself.

In life, we expected to find ourselves, but the more we sought self, the further away self remained. Autonomy was supposed to bring freedom but instead resulted in ennui and despair. When the Law reveals the discrepancy between who we are and who we know we should be, we respond by ‘working’ in one capacity or another. In particular, romantic relationships become a chief vehicle by which we embark on the quest to know self. What we discover, though, is that “you complete me” quickly becomes “you confuse me.”

“For Want Of” immediately follows “Deeper Than Inside” and underscores this tendency, as introspection abruptly shifts to sober retrospection, namely, the realization that life under the Law doesn’t work. A wave of feedback gradually fades in as a catchy melodic pattern syncs with the vocalist’s syllabic emphasis:

I believed memory might mirror no reflections on me

I believed that in forgetting I might set myself free.

Echoing Paul’s desperate cry–“Who will deliver me?”–the lyrics here indicate the inescapable implications of self-justification in relationships. We who long to relate to one another in the most intimate manner cannot avoid doing so without turning the relational dynamic into a forum for vindication. The romantic relationship needs to be a space free of judgment where we can be naked and unashamed (cf. Genesis 2:25), where, as the track “Nudes” (replete with its Edenic allusions) intimates, we can “talk like we’re talking to ourselves.”

Everyone wants fleshly intimacy where the line between where we stop and our beloved begins blurs into harmony. But alas, “when I want to do right, evil is present with me.” Or as Picciotto sings, “I wanna reach, but I could be someone else.” I want the freedom vulnerability affords, but I’m terrified of being judged–because I’m still working on figuring out who I am. I want to divest myself of self, but I can never move beyond the inborn inclination to self-justification. This narcissistic impulse explains a lot about why the psychological effects of a breakup linger and often reverberate sometimes years after the fact.

When a relationship ends, we know we should let go of the past, start fresh, seek a new lease on life, etc. But it’s so difficult. In fact, it’s impossible. I would argue it’s actually easy to let go of the past, but the past refuses to let go of us. We carry the haunting memories and wounds of failed relationships, things left unsaid, things we wish we hadn’t said, regrets, unresolved arguments … most of all, confusion over why the relationship ended in the first place. The pain and disillusionment of a failed relationship are so unbearable that we seek ways to justify the situation and ourselves. We can’t handle the heavy pain of loss … in short, we can’t bear the stinging accusation of the Law.

And the little l-law is clear: don’t be a failure. Don’t lose. Where life, love, romance, etc. pronounce the verdict “fail” over you, fight against it and seek to make meaning–even where there apparently isn’t any. Instead of calling a bad situation a bad situation, our human proclivity is to try to “make lemonade out of lemons,” or, as Picciotto sings later, to attempt to see that “every wall is a door to somewhere new.” This sort of theology of glory espoused by both the churched and the unchurched makes no concession for real-life hurt and sorrow. In it, there’s an implicit demand that we find the silver lining in our troubles. The reality may be that there isn’t one.

We know optimism is supposed to work here. But let’s be real. It never does. When we’re viscerally experiencing the real pain of the loss of love, it never comforts when those who (think they) mean well tell us, “It’s time to get over it,” “It’s their loss,” or, as I heard one minister say, “When someone rejects you, they weren’t ready for all you had to offer.” We know we should believe this. We know this should console us. We want to believe it, but the internal voice of the law out-volumes our best attempts at self-coaching. Rejection fires an arrow at our sense of worth, inducing shame. Try as we might to resist a lethal word of ‘law,’ we eventually realize we are powerless and we inevitably own the accusation as our very identity. In short, we embrace the verdict that we are not enough, despite trying to make ourselves believe otherwise.

We fear pain and loss and therefore refuse to call them by their names because they always leave us vulnerable and remind us we’re not gods after all. We are helpless and broken, petty and fickle. We need God. And we will do everything in our assumed power to militate against this truth.

We do all we can to avoid the pain, avoid the weakness, avoid the vulnerability, forget our failure in the relationship. While no one wants to be that person who can’t move on, no one can help being that person who can’t move on. That’s how the law works — I agree with what’s good and right … but I have no power to carry it out. And this is the dilemma of saint and sinner alike.

“By Your Own Design,” the album’s ninth track complements “For Want Of” in that it expounds on our tendency to stay in the past, replaying the old tapes, rehearsing worn-out, expired arguments. After a breakup, we assume, of course, we were right and they were wrong. We revisit the crime scene in search of new evidence to vindicate us. Often, memories we expect to serve as allies in this process work against. Replaying the past doesn’t solidify our argument; it nullifies it. What we can’t see in the midst of relational tension is the self-centeredness we contribute. That’s only knowable as we see things in reverse. Memory damns us as the subconscious spontaneously, unexpectedly, shows us ourselves. A random recollection of an archived argument, for example, affords us a heretofore unseen disclosure of our arrogance, of our lack of consideration, not our partner’s assumed flaws. When I review (voluntarily and involuntarily) the narrative, I find my alibi doesn’t hold up.

The song, “Persistent Vision” reinforces this:

I was the champion of forgive/forget,

But I haven’t found a way to forgive you yet,

And though I know you and I are through,

All my thoughts are lines converging in on you

The songwriter validates forgiveness as that which sets us free: To the extent that we can forgive someone, we can in fact move on with our lives. But we find we can’t forgive; more specifically, we can’t forgive people for not being us. Hence the line in “Hain’s Point”:

And I read somewhere that every wall’s a door to somewhere new

Well if that’s true, why can I get through?

Cause you’re not who I thought you were …

We hate people for failing; rather, for refusing to be/complete us. Because that was our expectation when we got into the relationship in the first place. Picciotto confirms as much as he recounts with regret on “For Want Of”: “I bled in the arms of a girl I barely met.” In other words (and yes, I have done it too many times in relationships), I gave someone too much too soon, hoping they could answer the deepest questions of my soul: “Do I matter? Who am I? Am I enough?” We disclose ourselves to the object of our infatuation looking not so much to know them, but ultimately in hope they can help us know ourselves. From our vantage point, they were a glorious horizon that has now faded (cf. 2 Corinthians 3:7-14) yet once seemed to promise to be “all” and “everything” for us.

It’s actually a traumatic experience when the person we imagined and needed them to be mercilessly dissolves into who they are, when the pedestaled version of “them” transforms gradually into the real them. The god we made them into becomes the sinner we refused to give them room to be. And in making them a god, we are acting out of our desire to make ourselves gods. So they fail us in what we expected them to help us do—deify ourselves.

But there’s hope, and incidentally, it’s not found on the last song of the album–just as Ecclesiastes doesn’t ultimately conclude with “the answer.” Ecclesiastes is often thought of (and preached) as consummating definitively with “let us hear the conclusion of the matter: fear God and keep His commands, for this is the whole duty of man.” But Ecclesiastes 12:13 is a word of law, a declaration that the Law is in fact good (Romans 7:12). But this reinforcement that trusting God would give us meaning, joy, and peace if we could keep the Law only serves as a diagnostic word, not a word of deliverance.

Similarly, End on End‘s trajectory nearly concludes with the twelfth track “Nudes” in which the punk rock prophet realizes, concerning the inward search for meaning, ‘”I know enough not to hope to know.” This is the confession and ache of someone whom the law has exhausted to the point of true wisdom. The law’s work is always to show we can’t keep it. Cue Proverbs 30:2.

“Nudes” brings the album full-circle, as it testifies that the sentiment expressed on “Deeper Than Inside” doesn’t work. The trek to know self is literally a dead end—i.e., we never get to the bottom of understanding ourselves. In short, we can’t in fact become gods, knowing good and evil. Justifying ourselves never brings life. Yet instead of pivoting to a clear articulation of Gospel hope, there’s an apathetic resignation to life under the Law, akin to “let us eat and drink, for tomorrow we die” (Ecclesiastes 2:24-26, 9:7-10, 11:7-9). The album ends on a note of despair as the songwriters resign themselves to nihilistic, stoic indifference in the concluding title track. It’s a cacophony, musically connoting the disintegration of meaning, hope, and existence. The imagery evoked by the line “restless movement in an empty room” aptly comments on the anxiety-inducing effect of the law as we struggle to make sense and meaning via our vain toil–including the hard work of relationships.

The grace to be found on this album is hidden in the middle track, much like the answer to Ecclesiastes is concealed in its penultimate chapter. Ecclesiastes condemns all of life as a chasing after the wind, yet Ecclesiastes 11:5 hints at a better wind, namely that of grace by which we must be apprehended (cf. John 3:8).

As you do not know the path of the wind,

Or how the body is formed in a mother’s womb,

So you cannot understand the work of God,

The Maker of all things.

The sixth track “Drink Deep” strongly suggests this grace, especially as Christians understand it vis-à-vis the Communion Table. Consider its lyrics:

Drink deep, it’s just a taste

And it might not come this way again

I believe in moments

Transparent moments

Moments in grace

When you’ve got to stake your faith

Why do I confine

When all I want is release?

It moves outside you

It stays inside you

And it’s not something that I could prove

Or could choose to be moved

Yes, it’s a promise and it’s a threat

And it’s not something that I’ll let you forget

Not just yet, not just yet

Why do I chase when all I want is near?

If it’s not the rule then it’s always the case

Good intentions get fractured

Good intentions get replaced

So close to reach but so hard to hold

The only chance you get is past your control

It’s so hard, it’s so hard

Drink deep, it’s just a taste

And it might not come this way again

Time to surrender

Sweet surrender of all things in time

All things one place, one place

This ironic quasi-hymn abounds with redemptive verbiage as the first line comments, “It’s just a taste / And it might not come this way again.” In this age, we only get a foretaste of the grace to come (cf. Ephesians 1:14). There’s a sense of those authentic, unrehearsed, spontaneous moments of living, of real sanctification happen to us. We have this anxiety; we don’t know how long we get to enjoy the freedom. Or as another eclectic post-punk outfit, the Violent Femmes, once sang, “Good feeling, won’t you stay with me just a little longer?” Transcendent moments of life and love are often few and far between, and we can’t will them to happen or retain them. They arbitrarily arrive and dissipate like the wind blowing where you do not know.

Law/Gospel insinuations continue as Picciotto sings, “it’s a promise and it’s a threat / And it’s not something that I’ll let you forget, not just yet.” In view here are the good times that were had in spite of the normal tension that typically characterizes romantic relationships. Despite whatever destroyed the relationship and the consequent blame-shifting, we can’t deny that there were some genuine moments of connection, if sparse. Track 10, “Remainder,” picks up on this:

I’ve found the answer lies in a real emotion

Not the self-indulgence of a self-devotion

I’ve found things in this life that still are real

Remainder refusing to be concealed

What are those things that still are real? From the last chapter of The Problem of Pain, C. S. Lewis provides invaluable insight here:

…you may have noticed that the books you really love are bound together by a secret thread. You know very well what is the common quality that makes you love them, though you cannot put it into words: but most of your friends do not see it at all, and often wonder why, liking this, you should also like that. Again, you have stood before some landscape, which seems to embody what you have been looking for all your life; and then turned to the friend at your side who appears to be seeing what you saw–but at the first words a gulf yawns between you, and you realize that this landscape means something totally different to him … We cannot tell each other about it. It is the secret signature of each soul, the incommunicable and unappeasable want, the thing we desired before we met our wives or made our friends or chose our work, and which we shall still desire on our deathbeds, when the mind no longer knows wife or friend or work. While we are, this is. If we lose this, we lose all.

If, as the track “Spring” indicates, we are in fact “caught in time so far away … reaching out to find a way to get back to where we were,” then we have to ask where were we? In an immediate sense, we would say we waste the present trying to recapture nostalgic moments, idyllic times when life seemed freer. We rehearse random vignettes from the scenes of our own micro-story where, through a perceived sense of general levity, we actually touched the fringes of the transcendent. More fundamentally, though, we are trying to get back to the garden, where we were once “naked and unashamed.” We are literally trying to re-cover ourselves.

Grace offers something infinitely better, though. Grace says we’re free from the bondage of having to cover ourselves. In the death of Jesus Christ, God has given us a perfect covering (2 Corinthians 5:21). Drink Deep betrays our unconscious awareness that the real things of life, the remainder that refuses to be concealed, belong to the invisible realm we can’t control—grace. Romans 1:20-21 and 2:4 insinuate that we intuitively know God is real and his grace is sufficient because our engagement with the stream of experiences “under the sun” (as Ecclesiastes puts it) serves as a shadow, a dim mirror reflecting the true substance, “even his eternal power and divine nature.” We know that all is essentially gift, but we suppress this knowledge in favor of pursuing work instead.

As “Drink Deep” reaches its bridge, we hear the essence of our chief internal conflict, “Why do I confine when all I want is release?” If all we want is rest and raw, naked freedom, why do we seek to contain, control, and save our lives? Why do I do what I do? I don’t understand (Romans 7:15). We may not understand why we do what we do, but the Gospel assures us we are known by the One who said It is finished. This Gospel is an external word providing relief as reflected in the lyric:

It moves outside you, it moves outside you

It stays inside you

And it’s not something that I could prove

Or could choose to be moved

The satisfaction of our desire to be known isn’t found in horizontal relationships, except perhaps for intermittent glimpses of what is only fulfilled in Christ. In him, we have a cup whence we can eternally drink deep, because of the cup from which our Lord drank all our worldly ambition and pride, including our commitment to be “deeper than inside.” When we eat the bread, and drink the wine, we stake our faith in a transparent grace. For as Picciotto rightly summarizes, “the only chance you get is past your control.”

COMMENTS

2 responses to “The Unintentional Theology of Rites of Spring, Or, The Gospel According to Guy Picciotto”

Leave a Reply

This is peak me. Great piece, glad someone else has thought about Guy Picciotto’s tortured soul.

This is all completely new to me!! I am really excited to dig in. Thank you so much, Jason, for this incredibly thoughtful and thorough post.