This article is by Jonathan Jameson:

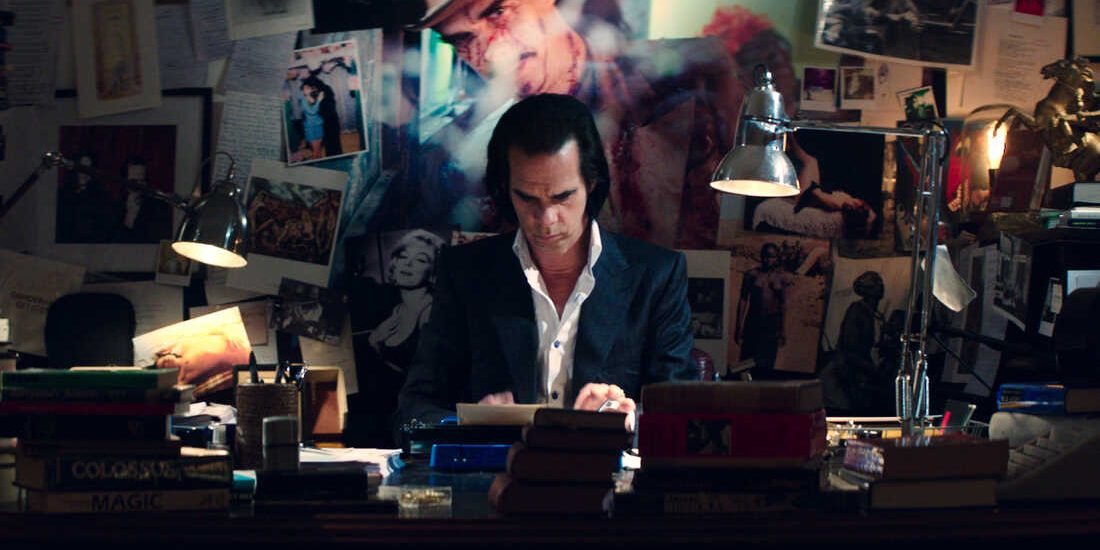

On the back of Nick Cave and Seán O’Hagan’s Faith, Hope and Carnage is the simple statement that puts this remarkable book in the right light. It reads, “This is not a memoir, this is a conversation.” When I first saw this little blurb I was bummed. I thought what I wanted was a long, linear exposition on a thoughtful musician’s life. But, boy was I wrong. What I encountered just kept surprising me.

Faith, Hope and Carnage is a unique and strange book, dealing as it does with the entangled themes of grief, and faith, and art, and longing — often with Cave’s unmatched extemporaneous lyricism. But it is precisely the entangling of the themes that makes the book difficult to write about. I’ve tried multiple times to summarize what I love about this book it always just seems to fall flat. But I think that I’m finally beginning to understand just why this is.

Conversation is a gift, a sort of miracle. Like art or prayer it is something that one can set the scene for, but one can not make it happen. There is something mysterious to it. And when it is gifted, when we find someone who will be patient with us, vulnerable with us, creative with us — someone who is very much other than us — something changes within us. We learn things that we did not know about ourselves. We learn that other people are not who we thought they were. It is simultaneously intimate and expansive. We feel ourselves open up and it is in these moments that God just might break through.

In Faith, Hope and Carnage we are invited to eavesdrop on real conversation and it is unbelievably exhilarating and refreshing. Who knew we needed it so badly?! Maybe it’s the constant flow of monologued news that we were forced to endure during the pandemic? Maybe it’s the ease of evaporating our time with the illusion of connectivity that is social media? Maybe it’s the impoverished state of political discourse, or of religious engagement, or of being able to stomach anyone who disagrees with us. We hear all of this stuff constantly and though it’s all likely quite true, often these cultural critiques take the form of yet another self-confident monologue. And another self-confident monologue is the last thing that we need right now. We’re all sick of “hot takes” — these little unsolicited dishings of “wisdom” which always seem to have a demeaning edge to them. We are starved for conversation.

Nick Cave and Seán O’Hagan may like the same bands, but outside of that they have very different understandings and experiences of the world. O’Hagan is a music journalist who grew up in the religious and political maelstrom of Northern Ireland. Raised Roman Catholic, he has mostly renounced his faith in favor of socialism and scientific reason. That said, his journalistic approach seems to be marked by an unexpected openness.

Cave, on the other hand, was raised in rural Australia in an Anglican family, eventually singing in the cathedral choir as a boy. He recalls being deeply attracted to the religious at a young age. But this is something that age and bad sermons seemed to complicate for him. He eventually found himself estranged from the Church but still powerfully taken by scripture, deriving lyrical inspiration from the severity of the Old Testament and eventually reacquainting himself with the Christ that he was drawn to as a youth in the Gospels. In the 1990s he wrote a compelling, if unorthodox, introduction to the Gospel of Mark. Even though Cave generally disregarded the more challenging articles of faith, he simultaneously had the sense that all of his songs were really about God. In lecture at the Vienna Poetry Festival in 1998 entitled “The Secret Life of the Love Song,” he made this powerful assertion:

Though the Love Song comes in many guises — songs of exultation and praise, songs of rage and despair, erotic songs, songs of abandonment and loss — they all address God, for it is the haunted premises of longing that the true Love Song inhabits.

But for most of his creative life he held the view that the artist “writes God into existence.” Was it he that didn’t believe in “an interventionist God” or was it one of his lyrical characters? But regardless it seems that eventually God did show up — in both terrifying and beautiful ways.

In 2015 one of his twin sons, Arthur, fell from a cliffside in Brighton, UK and was killed. This “obliterating moment” forever changed Cave. He eventually became aware that he would either harden around the absence of Arthur or he would let it transform him. And what he discovered is the backdrop of Faith, Hope and Carnage. Cave emerged from the depths of grief with his wife Susie and their son and progressively became aware that he related to the world in a different way than he had before. He no longer had the inclination to hold the world in contempt. Instead he felt a conviction, a calling, “to treat the world with mercy.” And he speaks in the book about his own longing for mercy and even absolution, suggesting that at the center of the universe is the shocking question: “Can we be forgiven?” Stating plainly that the secular world simply doesn’t know what to do with this longing.

Through all of this Cave started what can only be called a ministry of empathy with his platform the Red Hand Files, where he responds with unusual humanity and compassion to what are oftentimes very challenging and raw questions from fans in all sorts of differing situations and with widely diverse worldviews.

Faith, Hope and Carnage takes this instinct and puts it in conversation. And because the conversation is between two trusted friends, the intimacy and candor is natural and inviting. Though Cave’s words are what makes the book sing, it is O’Hagan’s conversational ability, not unlike a conductor in a symphony, that allows the ideas to soar. And as only a friend can, he occasionally challenges and pushes back which allows for the constructive possibility that real conversation affords. There are moments of surprise, of shock, even of speechlessness. There are moments when Cave and O’Hagan seem to influence one another. And there are also deep and unresolved differences. Yet in it all there is a palpable sense of mutually afforded mercy — a mercy that allows for a tangible flourishing of ideas and possibilities and of the humans which took part in the conversation.

The ideas in the book are often profound (if unfinished). But I’ve come to see that the greatest strength of the book is not in its counter-cultural ideas, or its lyrical exploration of coming to faith, or its tender and vulnerable treatment of grief, but in its witness to the goodness and necessity of conversation. It is an invitation to have our own conversations. To not be afraid to talk about God, and grief, and art, and the longing that weaves them all together. It is an invitation to make friends and to make space in our lives for those friends – to open ourselves to the challenge of vulnerability. It is an invitation to extend to one another the great and abiding mercy of conversation.

I read Cave’s Red Hand Files frequently….they are a gift