Thought I’d kick off the new year with the introduction from A Mess of Help: From the Crucified Soul of Rock N’ Roll (minus the footnotes), something of a personal essay and one which spells out a bit of the thinking behind this whole Mockingbird project.

It was the kind of question that sticks with a person, especially when they’re seventeen. My father asked me one day, out of the blue, “What do you think matters more to people your age—music or movies? Which has more influence?” Even then, I knew enough not to speak for ‘people my age’. But my own answer was obvious. While I loved movies and television, music was different. I identified with music. The movies I enjoyed most at that point were ones that transported me elsewhere, usually through humor or fantasy. Music, on the other hand, resonated with what was going on inside. It gave expression to feelings of frustration and melancholy and yearning. It drove everyone around me crazy.

It was the kind of question that sticks with a person, especially when they’re seventeen. My father asked me one day, out of the blue, “What do you think matters more to people your age—music or movies? Which has more influence?” Even then, I knew enough not to speak for ‘people my age’. But my own answer was obvious. While I loved movies and television, music was different. I identified with music. The movies I enjoyed most at that point were ones that transported me elsewhere, usually through humor or fantasy. Music, on the other hand, resonated with what was going on inside. It gave expression to feelings of frustration and melancholy and yearning. It drove everyone around me crazy.

But music did more than voice my emotions; it romanticized them. It turned teenage ennui into something larger and more glamorous, maybe even transcendent. And if there’s anything we can safely say about seventeen-year-olds—‘people my age’—they don’t shy away from melodrama.

All I knew at the time was that my relationship with Brian Wilson or Michael Jackson was personal in a way that my favorite actors—at that point Bill Murray and Julia Louis-Dreyfuss loomed large (and still do)—could never approach. Perhaps it was because the thespian’s art was more overtly fictional. A good story could pull on the heartstrings and tap on the funny bone, but a (good) album was less mediated, more private somehow. My favorite musicians were incomplete, always grappling with an ever-changing present rather than a finished narrative—like me. Their journey was my journey. Their pain was my pain. When they gained popularity, I felt justified (and cool). When they embarrassed themselves, I was embarrassed too. That’s what it means to be a fan, at least when you’re seventeen.

Most of this probably boils down to what goes on during adolescence, which is the process of figuring out who on Earth you are. It is the time of lunchrooms segregated by social group—preppies, hippies, freaks, geeks, athletes, etc. You don’t have to be a punk or a goth to know there are few stronger teenage identifiers than taste in music. I took it so seriously that I had a radio show in high school.

The problem comes, as it always does, when you find out that you cannot force yourself to like something you don’t. Or if you can, it only works for so long. None of us can dictate what moves or touches us. The heart likes what it likes; it does not discriminate between the latest Katy Perry single and an obscure Nick Cave B-Side. Only after our gut-level affections have made themselves known does the head filter things through self-understanding and ‘taste’. It should come as no surprise, then, that those things which connect with us most deeply tend to contain an element of surprise. They catch us off-guard and undefended, meeting us where we really live.

The problem comes, as it always does, when you find out that you cannot force yourself to like something you don’t. Or if you can, it only works for so long. None of us can dictate what moves or touches us. The heart likes what it likes; it does not discriminate between the latest Katy Perry single and an obscure Nick Cave B-Side. Only after our gut-level affections have made themselves known does the head filter things through self-understanding and ‘taste’. It should come as no surprise, then, that those things which connect with us most deeply tend to contain an element of surprise. They catch us off-guard and undefended, meeting us where we really live.

This can be pretty inconvenient, especially when what you actually like and what you feel you’re supposed to like turn out to be different things, but it also gives a clue as to what makes music, and art more generally, so subversive. Under the guise of escape and distraction, it is capable of connecting us with the reality of who and where we are—our unsifted feelings and desires—as opposed to who or where we think we should be. The great English poet W.H. Auden once wrote: “In so far as poetry, or any other of the arts, can be said to have an ulterior purpose, it is, by telling the truth, to disenchant and disintoxicate.” Nothing can cut through a feeble defense or assumed identity, nothing can bring us back to ourselves as quickly as the right song played at the right time. Supermarkets—and churches!—are notorious for this.

Not only can culture serve as a spiritual barometer of sorts, but also it can reach us at an emotional level so deep as to be shut off to more direct approaches. I would by no means be the first to expound on the power of indirect, peripheral communication, that is, the peculiar ability of art and story to circumvent our prejudices and assumptions. Jesus taught in parables, as the cliché goes. Art can do more than expose.

So what do the music I listen to and the musicians I love say about me? Well, as the table of contents makes painfully clear, the artists to whom I’ve tended to gravitate are predominantly sensitive and misunderstood men with vast wells of talent and a penchant for self-sabotage. These are men who were or are all opposed in some way, by others or themselves or both, but whose gifts could nonetheless not be quashed. They are tortured in some cases, occasionally victimized, yet filled with deep feeling and substance. To the wider world, what this often looks like is eccentricity.

Putting this down on paper makes me want to gag! Hopelessly romantic and embarrassingly self-serious, I suppose it is who I fancied myself to be, or who I desperately wanted to be, maybe still do.

Of course, the predilections weren’t arbitrary. Growing up, I had always been told I was ‘sensitive’. Nary a report card passed by without that descriptor popping up somewhere. It’s an unfortunate catchall, and not one that most adolescent boys take as a compliment. The identification wasn’t all fantasy or projection—I may not have possessed their musicality (remotely), and the only eccentricity to which I could authentically lay claim was my boundless fascination with eccentrics themselves, but I did share one talent with Axl Rose and Morrissey: a gift for generating self-pity at the drop of a hat. Maybe if they could turn their victimhood, misguided or not, into something useful (and more to the point, attractive!), maybe I could too. For better or worse, music became my way of making sense of both myself and the world around me. Thus my hard-earned cash from summer jobs went entirely to a CD collection, the bulk of which still makes moving houses a serious challenge.

Of course, the predilections weren’t arbitrary. Growing up, I had always been told I was ‘sensitive’. Nary a report card passed by without that descriptor popping up somewhere. It’s an unfortunate catchall, and not one that most adolescent boys take as a compliment. The identification wasn’t all fantasy or projection—I may not have possessed their musicality (remotely), and the only eccentricity to which I could authentically lay claim was my boundless fascination with eccentrics themselves, but I did share one talent with Axl Rose and Morrissey: a gift for generating self-pity at the drop of a hat. Maybe if they could turn their victimhood, misguided or not, into something useful (and more to the point, attractive!), maybe I could too. For better or worse, music became my way of making sense of both myself and the world around me. Thus my hard-earned cash from summer jobs went entirely to a CD collection, the bulk of which still makes moving houses a serious challenge.

Perhaps it should come as no surprise that when Christianity took root in my life, I not only found its core message of grace so exciting and enlivening as to be compelled to write about it, but music would become one of the primary lenses through which I came to do so. Not just music but culture itself—high, low and in between (T. Van Zandt).

In other words, it wasn’t that I set out to write about the intersection of Christianity and culture; it was simply the most honest language available to me—the lingua franca of my inner life, my immediate vocabulary for understanding what was happening to me. In fact, so immersed in it was I, that to avoid pop culture would have been to embrace precisely the kind of phoniness that permeates so much religious “engagement” with it these days. David Foster Wallace, another tragic and easily romanticized hero of mine, articulated the situation this way:

“In terms of the world I live in and try to write about, [popular culture is] inescapable. Avoiding any reference to the pop world would mean either being retrograde about what’s ‘permissible’ in serious art or else writing about some other world.”

Substitute “religion” for “serious art”, and you’re pretty close to the bone. Perhaps this explains why I find it irksome when the ministry that grew out of these convictions, Mockingbird—the venue for which the early sketches of nearly all of the essays contained in this book were written—is referred to as a ‘pop culture’ ministry.

Clearly we all employ shorthand to categorize our lives, and I don’t mean to begrudge anyone that tendency, especially since I frequently do the same with other institutions and publications. But I can’t help but detect a diminutizing spirit behind the label, as if invoking the authentic vocabulary of the everyday, instead of adopting a cautious register of formality, entails cheapening your true subject, in my case, the grace of God for sinners. Window-dressing or not, no one wants to be pigeonholed as juvenile, especially when what you are ultimately writing about, with its emphasis on death and guilt and reconciliation, is anything but. Thankfully, how the work is received is not up to me.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nTZiWlsw1Iw

This book represents the fruit of seven years’ worth of straining to see through that oddly shaped periscope. I’ve done my best to construct it like an album, where one song leads into the next, sometimes musically, sometimes thematically, sometimes both. Individual chapters work on their own, God willing, but also take on a further dimension when seen as part of the whole. There is a rhythm at work in this strange parade of characters. And given the material being discussed, I couldn’t resist providing a few potential soundtracks— to that end, several annotated playlists punctuate the longer pieces.

As Roland Bainton suggests, eccentrics have something valuable to teach us about ourselves, our world, and, most of all, the God that works in it. The particulars are revealed in the individual chapters, but perhaps a few broad sketches may be of assistance in taking those in.

One of the chief operating assumptions in this book is that there is only one reality. Which is another way of saying that there’s no difference between what is real for the religious person and for the non-religious one. Reality is singular; it applies across the board. We may interpret things differently from others, but those interpretations have little bearing on the truth itself. So the extent to which a song (or a movie or a joke) is rooted in something real will be the extent to which some connection can be made to truth.

Furthermore, it probably goes without saying that as a Christian, I believe that Christianity addresses reality, and as such, truth and Christian truth are not two separate things. I realize this is not a simple proposition by any stretch, but it is where the book is coming from, and part of what the essays illustrate. There is no way to avoid confirmation bias entirely; suffice it to say, I’ve done my best to present things in an honest and forthright manner.

What then is this truth that we see played out and corroborated in the lives and work of pop eccentrics? It’s myriad, but three dominant aspects are worth mentioning.

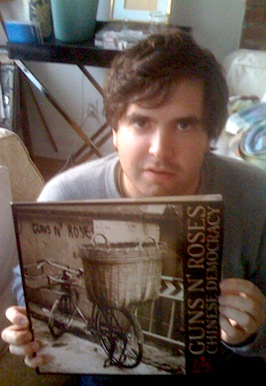

Nov 22, 2008, AKA, the day BEFORE it dropped. Never to be forgotten!

First, and most importantly, there is the truth of human nature, what the book of Job describes as “man born to trouble just as sparks fly upward” (5:7). We are our own worst enemies, and suffering, both self-inflicted and otherwise, is the tie that binds our species. ‘Original sin’ is simply human self-centeredness replicated and evenly distributed, and work which ignores this reality (and puffs up human agency) will fall flat—eventually. No school of thought has a more sober understanding of human limitation, or a more hopeful answer, than the Christian one.

It should come as no surprise, then, that music at its most universal—and popular—usually touches on some kind of ‘trouble’ or conflict. Control versus surrender, criticism versus acceptance, hurt and forgiveness, achievement and appeasement, the failure to love and the desire to be loved: as we will see, these are not just the major themes of life (and music), but they are also the major themes of the Bible.

If our shared humanity serves as the initial point of connection with pop eccentrics, two further realities we might recognize are those of law and grace.

What do I mean by ‘law’? Law refers to a basis of ‘righteousness’, whether it be civil or moral, any authoritative measure or standard from which judgments can be extrapolated. It could be the capital-L “Law” of the Ten Commandments or the Sermon on the Mount, the Oughts and Ought Nots we find there. But it could be the equally condemning echoes we hear from Madison Avenue (“Thou Shalt Be Beautiful or Successful or Intelligent”), or simply the internalized voice of a demanding parent, that feeling of never being quite enough which drives so much of our striving and exhaustion. The law’s exact form may be fluid, but its accusatory voice never wavers. It instigates the self-justification that occupies so many of our waking hours, as well as the resulting isolation and competition. All may have fallen short of the glory of God, but that hasn’t stopped us from comparing distances.

Oftentimes, the ‘secular’ world is viewed as an escape from the oppressive moral strictures of religion. Which it sometimes can be, for a stretch. And yet, as a number of the essays contained herein will testify, the ‘secular’ world can be just as condemning and judgmental, if not more so, as the religious one. The Law of Cool, for instance, often turns out to be a crueler taskmaster than the Law of God—the latter at least has the benefit of not being a moving target.

As much as we might wish it were not the case, we do not escape guilt or self-righteousness by leaving church—law is not an exclusively religious reality but a human one, as is the response to it: Faced with the nagging failure to be or do ‘enough’, we rebel and rationalize, hiding our true selves and wondering whether, and where, assistance is to be found. The Beach Boys perceptively sang, “you need a mess of help to stand alone”.

Which quickly brings us to the third point of connection, grace. As we see borne out in our own lives and those of other people, when it comes to lifting the human spirit, nothing is more potent than love in the midst of deserved judgment. If the law, at best, exposes our shortcomings, and at worst breeds total despair, then grace proves, time and again, to be the force that inspires service and creativity and hope and vulnerability and new life. Like law, grace is a reality so powerful that it transcends the ever-shifting zeitgeist and our fickle political sensibilities. It is no coincidence that grace lies at the very heart of the Gospel of Jesus Christ. Indeed, grace lies at the heart of the universe, “the love that moves the sun and stars” (Dante).

There are naturally some risks involved in a project like this. Lord knows I do not wish to assign spiritual intent or import where there is none, or reduce the power (and fun) of pop music by denying its ineffability. Nor do I mean to trivialize the claims of Christianity or venerate a culture that exacerbates self-aggrandizing and hurtful nonsense just as often as not. Fortunately, the song has not yet been written which can inflict wounds that aren’t already there or demolish the hope that was secured on Easter morning. We are free, in other words, to love—both our culture and those who are making and consuming it, which is everyone. We might therefore approach it, not with defensiveness and fear, but with curiosity and humor. To laugh and to cry and to play and be wowed and moved. To be surprised and to empathize.

Again, my hope is that tracing the unintentional but inescapable confidence with which some of this music points to both the tragedy of human life and its possible redemption can only deepen our faith. It certainly has mine. But even if it doesn’t, well, I trust that “our Merciful Friend” (B. Dylan) will live up to His name.

Click here to order your copy today .

.

P.S. Those who’ve already ordered, please don’t be shy about posting a review Amazon. Unless, you know…

COMMENTS

3 responses to “Why I Spent Last Year Writing a Book About Pop Music”

Leave a Reply

Dave, this is inspired! I’m loving the rest of the text too.

David,

I am not nearly as knowledgeable or passionate about music as you are, but I enjoy and appreciate your writing for this reason:

“The law’s exact form may be fluid, but its accusatory voice never wavers. It instigates the self-justification that occupies so many of our waking hours, as well as the resulting isolation and competition. All may have fallen short of the glory of God, but that hasn’t stopped us from comparing distances.

Oftentimes, the ‘secular’ world is viewed as an escape from the oppressive moral strictures of religion. Which it sometimes can be, for a stretch. And yet, as a number of the essays contained herein will testify, the ‘secular’ world can be just as condemning and judgmental, if not more so, as the religious one. The Law of Cool, for instance, often turns out to be a crueler taskmaster than the Law of God—the latter at least has the benefit of not being a moving target.

As much as we might wish it were not the case, we do not escape guilt or self-righteousness by leaving church—law is not an exclusively religious reality but a human one, as is the response to it: Faced with the nagging failure to be or do ‘enough’, we rebel and rationalize, hiding our true selves and wondering whether, and where, assistance is to be found. The Beach Boys perceptively sang, “you need a mess of help to stand alone”.

Looks like a really cool book! Can’t wait to read it… and recommend it!