This month’s edition of Christianity Today features a cover story, “The Return of Shame,” that draws a clear, causative link between the prevalence of social media and its corollary stripping of privacy with the emergence of a shame-fame culture. I couldn’t help but relate this to David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest (and Billy Idol’s “Eyes without a Face”).

n contrast to a guilt culture wherein morality is evaluated on the basis on individual conscience, a shame culture’s efficacy rests on community’s conception of your behavior. According to Crouch, “you know you are good or bad by what your community says about you.” This development–or shift, rather–has been accelerated by the prevalence of social media, in which the typical norms governing privacy have abated (Crouch uses the example of “doxxing,” or the public release of private and personal information). Social media has created a digital community where tweets are instantaneously biting, videos are seemingly eternally malicious, and others’ lives–via their heavily orchestrated profiles–are always on the upswing. If we truly believe that all are fallen, no one is off-limits. Everyone’s dirty-laundry is out to dry, and with billions now having access to social media, everyone can cast their stone. Not far behind this development lurks shame: “an inner sense of unworthiness, often rooted in trauma and embarrassing experiences.” This shame is well-documented.

To stay alive in a shame culture in the digital age one must garner fame. Thus, “In fame-shame culture, people yearn to feel included in the group, a state constantly endangered, fragile, and desperately in need of protection.” The number of likes, retweets, and YouTube views is the new SAT score of social media aptitude and the single determining factor in admission to the in-crowd’s Ivory Tower. As with any human-devised measure of worth, the shame-fame code is fraught with destructive implications: namely, no one can ever measure up.

A similar development occurred in Infinite Jest. Within DFW’s tome, a short section on the rise and fall of video-telephony gets right at the heart of our fear of the shaming that would inevitably result from authentic connections–those not grounded in fictitious profiles or open to the barbs of internet trolls.

One of the virtues of what DFW calls “aural” phones–or, in this case, one of the virtues of the pre-Facebook/Social Media era–was that we could bask in our own ignorance. We didn’t know the ins-and-outs of other people’s lives, particularly those with whom we didn’t have regular contact–and, as such, we had no grounds for assuming either the worst or best in others. Simply put, we just didn’t have the necessary data to render a judgment.

Fast forward to one of DFW’s years of subsidized time, and Interlace–his version of Verizon, AT&T and the like–has released a new, a seemingly more authentic and immediate way to connect with others. Sound familiar?

Even with high-end [teleputer’s] high-def viewer-screens, consumers perceived something essentially blurred and moist-looking about their phone-faces, a shiny pallid indefiniteness that struck them as not just unflattering but somehow evasive, furtive, untrustworthy, unlikable.”

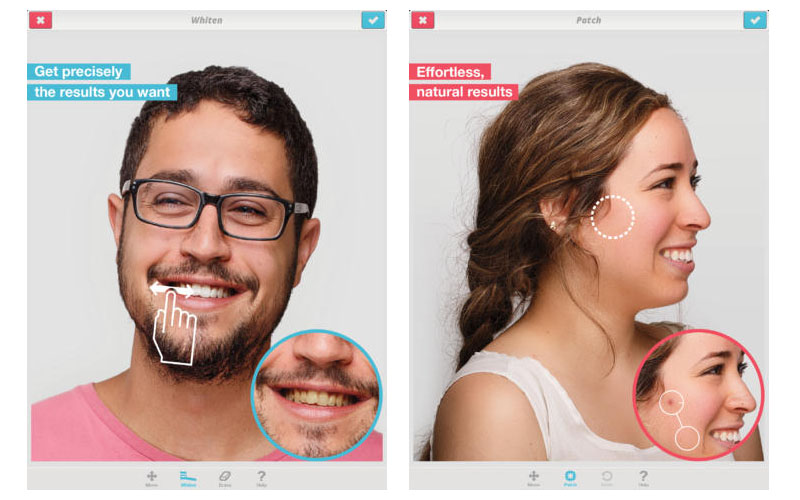

The reality of one’s own face, imperfections and all, led to the emergence of a new illness, Video-Physiognomic Dysphoria (VPD).

A variety of facial enhancements–including, but not limited to, wearable masks–ensued. Knowing that they could never look nearly as good as their well-preened masks, the videophone users avoided physical meetings lest people “suffer (so went the callers’ phobia) the same illusion-shattering aesthetic disappointment that, e.g., certain women who always wear makeup give people the first time they ever see them without makeup.” Eventually, the videophone would die a quick death, the masks would be discarded, and the old aural phone would return.

variety of facial enhancements–including, but not limited to, wearable masks–ensued. Knowing that they could never look nearly as good as their well-preened masks, the videophone users avoided physical meetings lest people “suffer (so went the callers’ phobia) the same illusion-shattering aesthetic disappointment that, e.g., certain women who always wear makeup give people the first time they ever see them without makeup.” Eventually, the videophone would die a quick death, the masks would be discarded, and the old aural phone would return.

In both Crouch and DFW’s accounts, the intended authentic connections afforded by technology have been supplanted by our own ill use and our fear of both shame and authenticity.

Enter the Cross. According to Crouch,

The cross, after all, was far from just an instrument of execution…[it] was specifically designed to maximize victims’ shame, from the whipping along the route to the place of crucifixion, to the stripping of every article of clothing…to the hours or days of exposure to the elements and the mocking of passersby.”

Perhaps DFW’s dystopia represents a kind of cautionary tale. The eventual demise of the videophone elicits a subsequent return to the traditional phone, through which callers remain blissful ignorance of one another–not necessarily a trip to Calvary. Yet, we believe that everything is eventually brought to light, which means that shame is never far away. If we are truly to subvert shame, what is needed is an authentic encounter with Jesus and grace.

We can sometimes take it for granted that Jesus knows us. If anyone were to ever have experienced shame, it was the Son of Man. That being the case, Crouch sees an opportunity for evangelism–and not just the saving souls kind–but the kind that invites the sinner into communion with the Son.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply