If Alcoholics Anonymous really is a model for the Church, then Raymond Carver has some of the best ecclesiology around! This time we turn to a story from his Cathedral collection about addiction, love, empathy, and (just maybe!) redemption. To read along, go here.

The next morning Frank Martin got me aside and said, ‘We can help you. If you want help and want to listen to what we say.’ But I didn’t know if they could help me or not. Part of me wanted help. But there was another part. All said, it was a very big if.

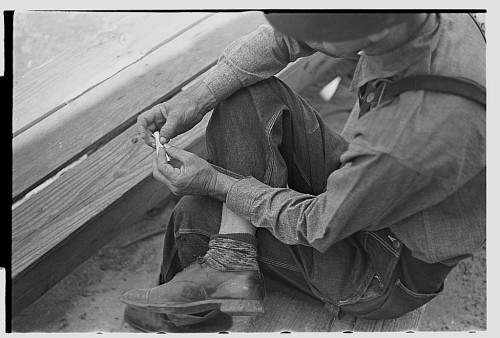

The story opens up with the unnamed narrator on the front porch of Frank Martin’s, a place to stay and dry out from alcoholism. He’s focusing on another man, J.P., a bizarre character who could’ve just as as easily been created by Flannery O’Connor as by Carver – and O’Connor’s influence (especially the writer of “Parker’s Back”) is more than palpable throughout the story.

The story opens up with the unnamed narrator on the front porch of Frank Martin’s, a place to stay and dry out from alcoholism. He’s focusing on another man, J.P., a bizarre character who could’ve just as as easily been created by Flannery O’Connor as by Carver – and O’Connor’s influence (especially the writer of “Parker’s Back”) is more than palpable throughout the story.

Addiction functions as the anthropological norm in this story, and Carver had more than a little experience with it in his own life. The alcoholic narrator, separated from his wife and distant from his girlfriend, describes his friend J.P. as “first and foremost a drunk” just “like the rest of us here at Frank Martin’s.” J.P. gradually unfolds his life story: he was impressed by a girl dressed in a black suit and a top hat who came over to his friend’s house to sweep the chimney and asked her for a kiss. “Sure,” she replied, “I’ve got some extra kisses.” He decided to be a chimney sweep himself, and eventually started dating and then married her. Everything in his life was going well and he was happy. But, J.P. tells the narrator, “‘I had everything I wanted. I had a wife and kids I loved, and I was doing what I wanted to be doing with my life.’ But for some reason [the narrator fills in] – who knows why we do what we do? – his drinking picks up.” Pretty soon J.P. and his wife are in fights, and finally her family picks up J.P. and makes him go to Frank Martin’s.

In other words, the proper self-knowledge and self-love of every created thing is ipso facto a participation in the knowledge and love of God.

-Robert Farrar Capon, Between Noon and Three

I don’t think we could call J.P.’s attitude here anything quite like self-love, but in telling his story and being honest about it, he’s coming to self-knowledge. In the end, when his wife comes and forgives him and embraces him, J.P. asks her in to coffee but tells her he needs a bit more time at Frank Martin’s. He’s gotten to know himself as addict, and he knows his need. The closing scene is by no means an ‘all’s well’, but he does “want help” and is “willing to listen”, to quote Frank Martin.

But the crux of the story is the narrator himself, whose characterization is more sparse and more complex than J.P.’s.What do we know about him? Mainly that he’s emotionally distant, divided from himself. He glosses over the most emotionally rich part of J.P.’s story, when he first met his wife Roxy: “he’s met somebody who could set his legs atremble. He could feel her kiss still burning on his lips, etc.”

Love is the narrator’s wound. The ‘etc’ is the only shortening or glossing over he does as he’s relaying J.P.’s story to the reader, and it’s not a stretch to say that’s because those emotions hit too close to home. The intensity of the narrator’s past romances also and simultaneously calls up images of guilt, how his alcoholism has had a hand in destroying something good. The narrator’s need for distance from his problems makes him tell his story more sparsely than he tells J.P.’s. Just as he “etc”-izes the emotional core of J.P.’s story, he gives no reason for why he’s split up from his wife, only that she’s asked him to leave. The fact there’s no mention of divorce, or any other reason, reveals his situation with her as unresolved, and in any case, it doesn’t seem like he cares too much about his girlfriend (he’s not called her since she dropped him off). Finally, he’s bought into J.P.’s story as a distraction from his own – it’s not that he’s interested in the story particularly, because he says “I was interested. But I would have listened if he’d been going on about how one day he’d decided to start pitching horseshoes.”

But stories can take on a life of their own, as can listening. The narrator’s drive toward self-distraction unintentionally midwife’s J.P.’s self-knowledge, his coming-to-himself. He might not be listening for the right reasons, but he is a good listener. And J.P.’s story begins to resonate with his, although it’s not until J.P.’s wife picks him up – and the narrator finally encounters a concrete possibility of redemption – that he begins to change.

The final scenes are brilliant. They meet J.P.’s wife on the porch. J.P.’s been drawn out of himself by his focus on his wife; the narrator’s being drawn out of himself by J.P. And so he (quite darkly and creepily) fixates on J.P.’s wife. He’s jealous, not of Roxy particularly, but of the fact that J.P. can still be loved by her, can love in return, and really does want to get better. He looks away when they hug – he cannot bear the possibility of reconciliation – and then reprises J.P.’s meeting her when he asks Roxy for a kiss himself. It’s a betrayal, because he’s trying to live J.P.’s narrative of redemption for himself. But nothing too bad comes of it, and Roxy gives him a kiss smack on the lips, and then leaves him to go inside. Carver uses the classic literary symbol of the threshold beautifully here: J.P. and his wife have gone in to the comforts of home and family, fire and hearth (Faulkner too uses the symbol), and the narrator’s left out on the porch, the in-between place, outside the place of love but lingering on its porch. The kiss from Roxy was demanded selfishly – embarrassing all parties involved – but it still serves as a sacrament of the real in his memory: unbidden, a memory of a typical morning with his wife comes into mind. Or in more Lutheran terms, his embarrassment brings up the memory of the real by contrast. Either way, something has broken through to him:

I bring some change out of my pocket. I’ll try my wife first. If she answers, I’ll wish her a Happy New Year. But that’s it. I won’t bring up business. I won’t raise my voice. Not even if she starts something. She’ll ask me where I’m calling from, and I’ll have to tell her. I won’t say anything about New Year’s resolutions. There’s no way to make a joke out of this.

Where he’s calling from: Frank Martin’s, the place where everyone is first and foremost alcoholics. The place of love is the place of vulnerability, or as Thornton Wilder put it, “In love’s service, only the wounded soldiers serve.” He’s calling from the place where he can’t offer her anything, can’t make any promises to change. Where we’re all calling from is the place of brokenness, pain, sin, addiction, and an extraordinarily big “if” about if we can get better, or if we even want to. But from that place – the place of honesty – contact can perhaps be made.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_detailpage&v=1-9_FT2Wr8c&w=600]

COMMENTS

3 responses to “Short Story Wednesdays: “Where I’m Calling From” by Raymond Carver”

Leave a Reply

Bravo, bravisimo, Will! What a video find there at the end! Have never seen these interviews.

Keenly done, Will. And merciful. Thanks. Reminds me of “All Legendary Obstacles” by John Montague:

“I was too blind with rain

And doubt to speak, but

Reached from the platform

Until our chilled hands met.”