(For the optimal reading experience, listen to the film’s soundtrack on Spotify while reading.)

The phantasmal kid films of the mid to  late 1990’s functioned as educational catechisms for my comprehension of cinematic storytelling. And make no mistake, the 90’s were a golden age for children’s movies. With the birth of Pixar in ‘95 and the far too premature peak of Nickelodeon Movies in the latter part of the decade, there surely was never a better time for school to be in session. There was, however, one common denominator, shared by nearly all children’s films, that severely irked me: the obligatory wreckage scene in which a catastrophic, implausible mess was created. Toys exploded out of bins, liberated animals ran rampant, food fights left walls and ceilings caked with condiments, articles of clothing fell victim to irreversible stains. And the worst part about it, the clean up scene, if there was one, was minimal. Audiences were left to believe that the mess just… lingered.

late 1990’s functioned as educational catechisms for my comprehension of cinematic storytelling. And make no mistake, the 90’s were a golden age for children’s movies. With the birth of Pixar in ‘95 and the far too premature peak of Nickelodeon Movies in the latter part of the decade, there surely was never a better time for school to be in session. There was, however, one common denominator, shared by nearly all children’s films, that severely irked me: the obligatory wreckage scene in which a catastrophic, implausible mess was created. Toys exploded out of bins, liberated animals ran rampant, food fights left walls and ceilings caked with condiments, articles of clothing fell victim to irreversible stains. And the worst part about it, the clean up scene, if there was one, was minimal. Audiences were left to believe that the mess just… lingered.

At the moment I am particularly plagued by a scene from Nickelodeon’s first film, Harriet the Spy. In an attempt to avenge their compromised reputations, the classmates that Harriet had spied on for so long gang up on her during an art class, spilling buckets of blue paint all over her. To make matters worse, they pretend to help clean her up, only spreading the paint over her even more. The classroom’s teacher, of course, is passively useless, and we never see Harriet properly cleaned up. She is left stained.

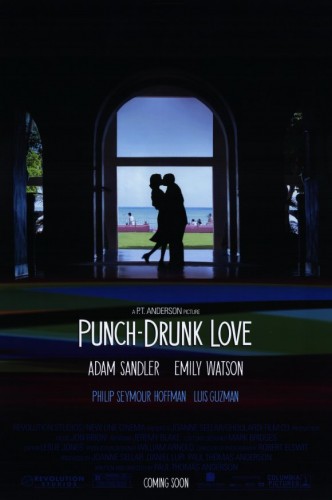

Perhaps ‘the mess scene’ is/was a technique used to G-rate the “I’ve lost all control” demeanor displayed in a scene of sexual impulse, or the “I’ve reached the end of my rope” condition demonstrated by a character who has been run into the ground by the horrors of addictions. By that logic, the mess scene certainly accomplishes its goal of disorienting the viewer (at least this viewer). They also made me cringe. To this day, I can still feel the tension gather in my shoulders as I recount specific scenes. And that is my long, drawn out way of explaining the feeling that Punch Drunk Love incubates throughout its entire duration: messy… but in the best possible way.

In Punch Drunk Love, Adam Sandler delivers the performance of a lifetime playing the lead role of Barry Egan. Barry is a single and friendless, insecure man who is content to skulk through life, hoping to avoid its pressure points. His sole community exists within the nagging encasement of his seven sisters. While the sisters receive limited screen time, it is clear that they have been making Barry’s life a living hell for a long, long time. They fire infiltrating questions at Barry’s personal life with menacing repetition. They cloak their disapproval of Barry’s life with a thin, fragile blanket of care. This is seen early on in the film when the sisters, in an echoic fashion, call Barry on the phone while he is at work to ask if he will attend a family party:

Sister One: “Are you going to this party?”

Sister Two: “I’m just calling to make sure that you show up at this party tonight.”

Sister Three: “You going to the party tonight? … What time are you going to be there? You can’t be late. I’m serious. Seriously. You can’t be late. You can’t just not show up like you do. Seriously.”

Their bludgeoning is nonstop, and Barry delivers the same answer, with a fabricated calmness, to each sister, “Yes I am.” Until Sister Four shows up at his workplace. She, of course, asks him the same question, and he, of course, delivers the same soft-spoken response, until she adds that she wants to bring a co-worker, a female co-worker, for Barry to “meet”. The impending awkwardness of a blind set-up paired with the probable, failing doom of such an event is not near worth the risk. Barry shows a sliver of honest, but necessary vulnerability in the wake of what would surely turn into a dreadfully uncontrollable night, “Yea, I don’t want to do that. I don’t do stuff like that… There’s an outside chance I don’t even come tonight… Please don’t (bring her).” She doesn’t, and Barry, uncomfortably, attends the party.

Despite all of his efforts to orchestrate an ordinary night, it takes quite a different course: Barry launches a chair through a sliding glass door. His action is sudden, but not entirely unexpected. It is the bursting sum of all seven sisters continued antagonizing. What Barry’s chair throwing does do is loosen, if even just a tiny bit, his grip on life, similar in manner to a child’s slipping fingers on the monkey bars. Once there is the slightest bit of movement, it is only a matter of time until both hands must let go.

Barry opens up to his family, admitting that he doesn’t “like himself sometimes,” but he is heartlessly mocked. He calls a phone sex hotline that results in more of a headache then any sort of tangible enjoyment. Besides, what Barry wants more than pleasure is connection, a reciprocated love or even “like”. His halfhearted searches come up empty again and again until, ironically, what he is searching for finds him. She finds him. She is Sister Four’s coworker, Lena Leonard played by Emily Watson. The woman he so badly did not want to meet. When Lena enters Barry’s life, she slowly peels his already loose fingers from those proverbial monkey bars.

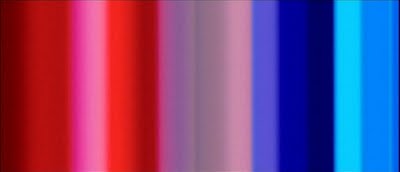

PDL’s meticulousness creates a surreal and emotionally exhaustive experience. Vivid blues and reds and pinks are decisively placed to highlight a scene’s emotion. Silhouetted, shape-shifting lighting evolves into bright and white-washed in the blink of an eye, affording the audience the ability to tap into Barry ‘s capricious state of mind. Jon Brion’s brilliantly composed, but frantic and bipolar, score makes rapid movements from heartwarming to horrific. The film’s elemental appeal to the human senses acts as the shaky easel which supports the splatter painting that is Barry’s unsure life. It’s an outlandish canvas.

During the early segments of the film, I couldn’t help but view much of Barry’s life as unrealistic, and there was a real temptation to allow myself to be okay with that. However, as the story progressed, I began to wonder more and more if what the audience is exposed to in PDL may be Barry’s projected life, rather than his actual life. Let me explain. It is common, at least for this writer, to formulate imaginative outcomes, composing conversations in my head before they happen. Usually this is done before walking into a situation where negative consequences are anticipated. It’s a defense mechanism, a blueprint to maintain control. If I ever need to ask for help from or defend a decision to a friend, family member, or co-worker I pre-play the conversation in my mind over and over again before it actually happens. Usually it looks something like this:

Joe: “Hey, ‘Co-worker!’” (False excitement in order to disguise the issue at hand)

Co-worker: “Joe… why did you do _______? (The initial accusation is made, always far more confrontational than it ever would be in reality)

Joe: “Oh you mean ________? Ya, I wasn’t thinking clearly at the time, but I’m pretty sure things will work out better now anyways.” (A frail admittance of mistake rapidly followed up with a twisted rebuttal to eliminate the consequences of the perceived wrongdoing)

Co-worker: “No, actually you’re wrong, and here are all the ways you screwed up….” (The discrediting final remark that makes sure to highlight all the flaws I had hoped to camouflage)

This is what I interpret most of PDL to be: a constant warm up round for Barry before he enters into the boxing ring of reality. When the audience witnesses Barry’s sisters fire encroaching questions at him, maybe we are really seeing and hearing how Barry projects and expects his sister’s to respond disapprovingly to his life. Maybe the reason Barry’s defensive responses appear to be so blemished is because we see, first hand, Barry’s bullshit-formulating process. For heaven’s sake, that’s even Barry’s literal business–he owns a plunger manufacturing company. What the audience sees is a different kind of reality: a projected one that everyone creates for himself or herself. It was not until looking at Barry’s life through this unique lens, that I could truly connect with him as a character. Who of us isn’t familiar with the fatigue that accompanies the attempt to control perception and identity?

Yet, Lena Leonard shuts down Barry’s BS factory. She seeks Barry out in his darkest, quirkiest places, and allows him the space to pursue her. Lena’s friendship with Sister Four provides her with the insight necessary to steer her away from Barry, yet it only pushes her closer to him. What Lena does not know, Barry longs to tell her. The charm of an honest love lures Barry into uncontrollable places. Barry wants to confess his mistakes to Lena while accepting and returning her affection. Her attention changes Barry. In fact the only scene in the whole film where Barry is not wearing his tacky blue suit, is a scene where he lies in bed with Lena, wearing a bathrobe. Stripped of his fabrications, all that’s left is pure Barry. It’s in scenes like these that we hear the heartwarming parts of Jon Brion’s score.

Barry’s mess is not exonerated through the acquisition of this love. It’s surfaced, available for viewing to the naked eye. His mess is made messier, if you will. But he is loved despite his mess. Don’t we all need that kind of love? Couldn’t we all afford a love that does not ignore our faults, but covers them? A Punch-Drunk Love? (Ephesians 2:1-10)

Check out Punch-Drunk Love on Netflix, and let us know what you think!

COMMENTS

11 responses to “Mining Netflix: The Common Mess of a Punch-Drunk Love”

Leave a Reply

This is so good, Joe. Great piece.

This has always been my least favorite PT Anderson film (probably because it’s the most askew from his typical style) but since I haven’t seen it in years I’m apt to rewatch through the lens of “Barry’s projected life”.

Sidenote: It’s interesting that two of Sandler’s best performances are serious roles (Punch-Drunk Love and Reign Over Me). Maybe he needs to give slapstick a rest.

Ethan, I agree. He’s in a new indie drama coming out later this year, called “The Cobbler”, where he supposedly showcases his serious side again.

Great post on a great film, Joe. Thank you! And I for one cannot WAIT for The Cobbler, which also happens to be the next film from Tom McCarthy, the dude behind three of my favorite big-screen ‘grace in practice’ fables of the past 15 years or so (Station Agent, The Visitor and Win Win). Unlike poor Sandler (but much like PTA), he’s yet to make a bad film. This bodes well.

Some Tom McCarthy love! Nice! All 3 of those films are great. I always recommend those films to anyone who asks what movies they should see next. There’s a certain “grace rhythm” to his films for sure.

I need to go back and watch PDL again. I liked it, I just don’t remember it. Great post.

Thanks Howie!

One of my quirky favorites. Also, one of my favorite characters played by Phillip Seymour Hoffman.

Sandler was also very good in Spanglish, though the film itself doesn’t quite live up to his performance.

A friendly Mining Netflix update: Spanglish is now available for viewing on Netflix.

Interesting take on PDL, Joe.

I think I’ve always had a similar feeling about the sisters. I think you just put it into words. I always thought, “How could he have seven sisters who all treated him exactly the same?” All disapproving, all shaming, all accusing. But your projection idea makes a lot of sense. His sisters treat him the way I usually treat myself when I feel threatened, cornered, ashamed, unsure…which you notice when watching, Barry always is feeling. He’s literally in a corner or looking over his shoulder quite often.

David: Thank you! I will have to check those films out now!

Pseudo: I’m a big fan of Spanglish as well. Sandler definitely has a more natural talent that doesn’t get tapped into much.

MW: Good observation on the being in the corner, and looking over his shoulder. It was such a difficult movie for me to enjoy until I could draw the personal connection between myself and Barry.