This post comes as somewhat of a very late retraction. Ten years ago I wrote a Mockingbird piece about Akira Kurosawa’s 1952 cinematic masterpiece Ikiru, which in Japanese means, “To Live.” The point at which I wrote that post was a different time and place, and the weight of living tends to change one’s views.

This post comes as somewhat of a very late retraction. Ten years ago I wrote a Mockingbird piece about Akira Kurosawa’s 1952 cinematic masterpiece Ikiru, which in Japanese means, “To Live.” The point at which I wrote that post was a different time and place, and the weight of living tends to change one’s views.

In Kurosawa’s film, a middle-aged government bureaucrat named Kanji Watanabe has been living for thirty years without really living. His wife died when his now adult son was a little boy, and Watanabe has never remarried. Instead, he has sought comfort in his work, to the exclusion of any real and close relationship with his son. Watanabe has thus spent the bulk of his life engrossed in the mundanity of his daily routine. But when Watanabe is diagnosed with stomach cancer, everything in his life turns upside down, and as a result of it Kanji Watanabe learns to live.

At first, he seeks life in all of the usual (and generally wrong) places–drinking, carousing, women–but none of these bring any satisfaction or relief. Instead, he finds what he needs when he reconnects with a young woman from his office who has sought him out in order to get his signature on her resignation form. This young woman is so vivacious and alive that as a result of her friendship, Watanabe begins to figure out what he needs in order to reconcile the impasse between his life not fully lived and what is now for him a looming termination date. To his family, Watanabe’s pursuit of the young woman is quite scandalous, and the young woman even begins to protest. It is in a climactic moment while the two are out to dinner that Watanabe finally spills the beans about his illness. He explains to the young woman that his motivation in pursuing her is simply to understand why she is so full of life. What he wants more than anything is to experience just one day of such alive-ness before he dies.

The young woman had recently taken a job working in a factory that manufactures wind-up rabbits. She takes one of these rabbits out of her purse, winds it up, sends it hopping across the table, and tells Watanabe, “When I help to make these in the factory I feel as if I am helping every baby in Japan. Perhaps that’s your answer: find something to do that will help others.”

This is just what Watanabe decides to do. He returns to work in order to resurrect a public works project that had long since died in the “circular file.” It was a project to bulldoze a neighborhood cesspool and replace it with a children’s playground. At the beginning of the movie, there’s a scene in which the mothers from that neighborhood are trying to present the playground proposal to local officials, and the circuitous run-around of government bureaucracy ends up overwhelming them. Watanabe decides that he will use his thirty years of bureaucratic experience to bring their project to fruition.

The second half of the movie is Watanabe’s funeral reception, and the outcome of his efforts to build the playground are told retrospectively. What we learn is that he became fearless in standing up to local officials because he felt that he had little time and nothing left to lose. He became single-minded and determined, willing to suffer any injury or insult in order to see the playground built. There’s one moment when Watanabe must stand up even to the local Yakuza thugs who try to scare him into backing down, and a look comes over his face. The look is unmistakable. In that moment, Watanabe finally senses that he is in fact living!

I bring all of this up, as I said, as a matter of revision. Ten years ago, I was forty. Now I am fifty, and smack-dab in the middle of what Paul Zahl in his most recent book, Peace in the Last Third of Life, would call the middle third of life. I am in that period of pursuing career and childrearing and all of those things that I believe are important and which I believe give my life meaning. These things fall away, Paul tells us, when we reach the last third of our lives. But what happens to us, I wonder, when perhaps any one of us, like Watanabe, receives an adverse terminal diagnosis? Suddenly, no matter which third we’re currently negotiating, we are immediately moved into the last third of life. Yet Instead of having twenty or thirty years to work through the hurts of the first third of life, we have what time we may be allotted, and that flame which can burn for only a short time ends up burning all the more brightly.

This is what I missed ten years ago in my consideration of Ikiru. At forty I saw only the tragedy of the story, and lamented what I saw as an absence of God. At fifty, though, as I look towards the far horizon and can begin to sense that last third of life approaching, what I now see in the story is beauty, and love, and God. Tolstoy was right, where love is there God is also, and love turns out to be the very heart of this film.

In Matthew’s Gospel, Jesus tells us to worry not for tomorrow, for tomorrow will worry about itself. What if you and I learned to live into the reality that tomorrow isn’t even promised? How might such terminal possibilities change the way we live? The way we love? Consider the petitions we make to God every time we pray the Lord’s Prayer. We ask God to give us bread for the day, to forgive our sins, and to save us from the time of trial. We never once ask for tomorrow, and in this time of global pandemic, the absence of a promised tomorrow is more acutely evident than it has been in at least a generation.

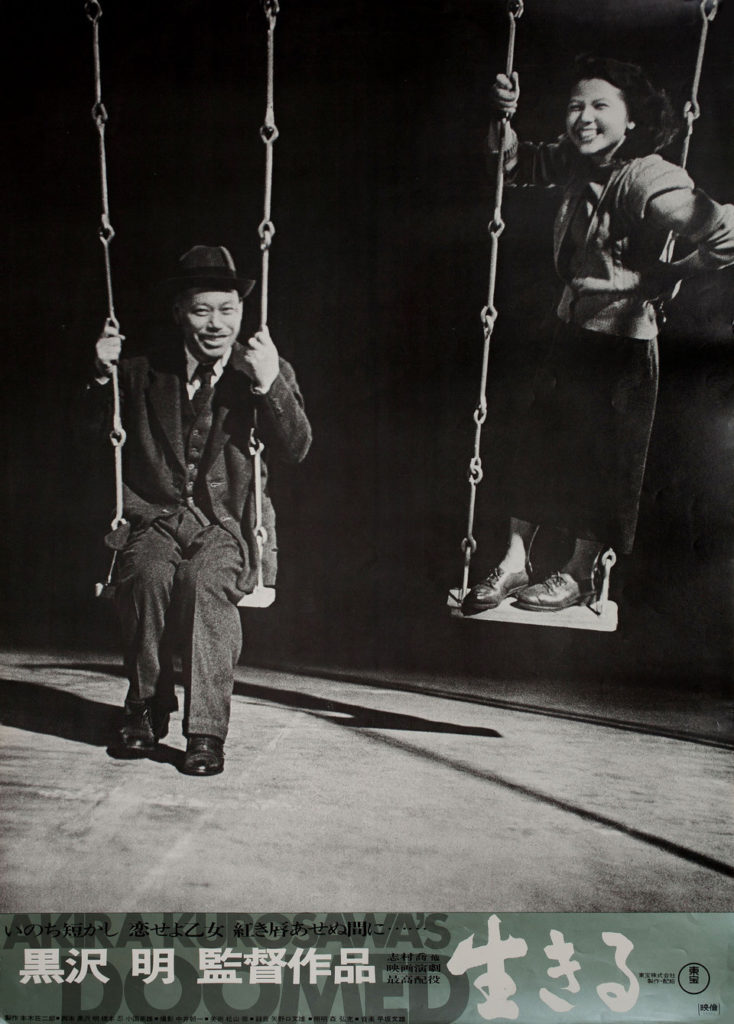

Jesus tells us in his Sermon on the Mount to seek first the kingdom of God, and to stop worrying about the rest. Perhaps it is in seeking the kingdom of God, today, in light of no promise of tomorrow, that even in the midst of our fear, even in the midst of anxiety and doubt, you and I find what it truly means to live and love. Watanabe found it in a playground that would not have existed without him. In fact, he dies on the night the playground is completed, swinging on the swing set and singing an old song entitled, “Life is Brief.” If God is love, and heaven is the presence of God, then Watanabe’s playground is an apt metaphor for heaven, with the love and life that Watanabe finally finds living on in the playfulness and laughter of grateful children.

COMMENTS

4 responses to “Ikiru: “To (re)Live””

Leave a Reply

Thank you Jeff, for a wonderful metaphor and image of love and life enjoyed on a swing set. Looking forward to your future insights on living life awake, in 2030!

Love this Jeff. Time for me to finally watch! Just took in Red Beard for a second time and wowza.

Jeff, I love this. Thank you for writing it. I love Ikiru and this made me want to watch it again. Even more so, it moved me to seek and show love today, for as you (and Tolstoy) say, there God is also.

[…] From another writer: […]