This one may make you cry. Even if, like me, you don’t know much about college football. I’m referring to the jaw-dropping story by Wright Thompson about (in)famous Ohio State coach Urban Meyer that ESPN Magazine ran in August. It is easily the most powerful account of Law and Grace I’ve read this year, not to mention a touching look at father-son relationships.

This one may make you cry. Even if, like me, you don’t know much about college football. I’m referring to the jaw-dropping story by Wright Thompson about (in)famous Ohio State coach Urban Meyer that ESPN Magazine ran in August. It is easily the most powerful account of Law and Grace I’ve read this year, not to mention a touching look at father-son relationships.

The piece paints a stark portrait of “performancism,” i.e., what it looks like when one’s self-worth is synonymous with one’s achievements, when failure is not an option–in theological language what’s known as “works righteousness.” Of course, performance is a necessary and important part of competitive sports–if there were no winners or losers they’d be pretty boring/pointless. The -ism comes in when the outcome of a game becomes more than a verdict on relative ability but on the people involved, period. (Just one of many reasons that sports are such a fertile, er, field for illustrations of judgment and love). As Meyer’s tale so vividly illustrates, it doesn’t matter who we are, how determined or gifted we may be, the burden of perfection (you must win, win, win and never stop winning) takes no prisoners. Or, you might say, it only takes prisoners. All have fallen short of the glory of Saban, as it were.

The article begins with a textbook description of father as lawgiver, i.e. arbiter of (impossible standards of) approval that would almost be laughable if they weren’t so damaging, ht TT:

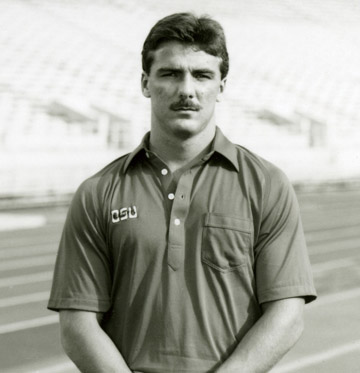

Like any man who destroys himself running for a finish line that doesn’t exist, Meyer often longed for the time and place where that race began: Columbus, 1986. As a 22-year-old graduate assistant for the Buckeyes, right up the road from his hometown of Ashtabula, Ohio, each day brought something new. He romanticized the experience; in later years, when the SEC’s recruiting wars got too dirty, he waxed about the Big Ten, where it was always 1986, which was just another way of hoping he could look in the mirror and see his younger, more idealistic self.

It might have been genetic. His father, Bud [thought]: Hard work solves every problem. Never accept defeat. Stay focused on the future; reflection is weakness wrapped in nostalgia. Urban grew up in a house free of contradiction. Bud Meyer believed in black and white. “No gray,” Urban says.

…A chemical engineer, Bud enjoyed Latin and advanced mathematics, but when his son struck out looking in high school, he made him run home from the game. The Braves drafted Urban after his senior year, and when he tried to quit minor league baseball, realizing he wasn’t good enough, Bud told him he no longer would be welcome in their home. Just call your mom on Christmas, he advised. Not only did Urban finish the season, he told that story to every freshman class he recruited. His whole life had been unintentionally preparing him to coach; after baseball, he played college football at Cincinnati, and the stern men in whistles seemed familiar. Some boys rebel against demanding fathers. Urban embraced his dad’s unforgiving expectations, finding a profession that allowed him to re-create the world of Bud Meyer: the joy of teaching, the lens of competition, the mentoring, the pushing — the black and white…

He lost 15 pounds during every season as the head coach at Bowling Green and at Utah, unable to eat or shave, rethinking things as fundamental as the punt. Purging the weak, he locked teams inside a gym with nothing but bleating whistles and trash cans for their puke, forcing the unworthy to quit. The survivors, and their coaches, were underdogs, united. His children often asked why they kept moving. Shelley always said, “Daddy’s climbing a mountain.”

His desire to mentor battled with the rage that often consumed him, a byproduct of his need for success and his constantly narrowing definition of it. He threw a remote control through a television… His own body rebelled against the intensity: During his time as an assistant, a cyst on his brain often sent crushing waves of pain through his head when he was stressed. He kept coaching, moving up, each rung of success pulling him further away from his young wife and kids. A voice of warning whispered even then. “I was always fearful I would become That Guy,” he says. “The guy who had regret. ‘Yeah, we won a couple of championships, but I never saw my kids grow up. Yeah, we beat Georgia a couple of times, but I ruined my marriage.'”

Then he won the 2006 national title.

Bud Meyer joined him in the locker room [after the game]. They hugged, cried, and before Urban left, he took his nameplate from his locker as a souvenir… [But] Success didn’t bring relief. It only magnified his obsession, made the margins thinner, left him with chest pains. After the 2007 season, he confided to a friend that anxiety was taking over his life and he wanted to walk away.

Two years after he cried with his father, Urban Meyer stood on the field with his second national championship team, the 2008 Gators, singing the fight song. After the last line, he rushed into the tunnel and locked himself in the coaches’ locker room. He began calling recruits as his assistants pounded on the door, asking if everything was okay. Back in Gainesville, his chronic chest pain got worse, and he did test after test, treadmills and heart scans, sure he was dying. Doctors found nothing, and the pain became another thing to ignore. “Building takes passion and energy,” Meyer says. “Maintenance is awful. It’s nothing but fatigue. Once you reach the top, maintaining that beast is awful.”

A few months later, during the 2009 SEC media days, a reporter asked what it felt like knowing anything but perfection would be a failure. Meyer tried to laugh it off, but he walked away from the podium knowing the undeniable truth of the question. Success meant perfection.

The drive for it changed something inside him. For the first time, Meyer needed an alarm clock. Shelley called his secretary to ask whether he was eating. Unopened boxes of food sat on his desk. He lost even when they won, raging at his coaches and players for mistakes, demanding emergency staff meetings in the middle of the night. He stopped smiling. Days ended later and later. He texted recruits in church. He ignored his children, his fears realized: He’d become That Guy.

Six or seven hours [after Urban’s Gators lost to Alabama in the 2009 SEC championship game], around 4 a.m., Meyer said his chest hurt, and he fell on the floor. Shelley dialed 911. She tried to sound calm, but a few shaky words gave her away. “My husband’s having chest pains,” she said. “He’s on the floor.” …Meyer lay on his stomach, on the floor of his mansion, his eyes closed, unable to speak. Soon he’d resign, come back for a year and resign again, but the journey that began with hope in Columbus in 1986 ended with that 911 call and the back of an ambulance. Urban Meyer won 104 games but lost himself.

What’s being described here is the anti-Coach Taylor, a man who is under such severe personal condemnation (via the internalized voice of his father) that he projects that same scrutiny on everyone around him. And it works… for a while. But the fruit is telling. Even when Urban is fulfilling all righteousness, record-wise, he’s not doing it out of love of the game or the joy of shaping/shepherding young men but out of fear of weakness and the need to prove himself. Fear of what it would mean if he lost.

And even if the Law (the divine “ought”, which is good and true) were only a matter external accomplishment and not internal motivation as well (as Christ so clearly suggest in the Sermon on the Mount), it’s not a one-time thing. In its harsh light, successes are not really successes; they’re simply non-failures. Maintain maintain maintain! Can you imagine? (I bet you can). It takes total collapse to bring Urban to himself, and perhaps it is not surprising that the road back to health involved getting in touch with both his biological and psychological child(ren).

West Point came in the middle of a 13-day road trip with [his son] Nate, maybe the best 13 days of Urban’s life. The two helicoptered to Yankee Stadium, hung out for almost a week in Cooperstown, where they held Babe Ruth’s bat. “I was 7 years old again,” he says.

Back home, Urban slept in. Shelley couldn’t believe it, getting up around 7:30 to work out, leaving Urban in bed. When he finally dressed, he’d walk a mile to a breakfast place he loved, lounge around and watch television with the owner, then walk a mile back.

“His mind shut off,” Shelley says.

Shelley begged him to do this forever. She’d never seen Urban so happy. He coached Nate’s baseball and football teams. He played paintball. The family went out for dinners, and Urban was present, cracking Seinfeld jokes and smiling…

During the fall that Urban spent searching, as the rumors circled about his return to the game, Bud Meyer was slipping away. Lung disease had left him frail and weak. Urban used his freedom to visit whenever he wanted. Around the LSU-Alabama game, Urban and Bud watched a television news report about the open Ohio State job. Urban’s picture appeared on the screen.

“Hey, you gonna do that?” Bud asked.

“I don’t know,” Urban said. “What do you think?” Bud turned to face him, gaunt in the light. An oxygen tube ran to his nose. Twenty seconds passed, the silence uncomfortable. Thirty seconds.

“Nah,” Bud said. “I like this s— the way it is. I don’t care who wins or loses.”

His response couldn’t have been more out of character. Never before had Urban asked his dad for his opinion and not gotten direct, blunt advice: “I think you should … ” In his father’s answer, there was a measure of absolution — maybe for both of them. Sometimes walking away isn’t quitting. Sometimes, when the fire burns too hot, walking away is the bravest thing a man can do. Bud offered the best mea culpa he could, in his own way. Maybe he knew this would be one of their last conversations. Ambivalence was his final gift. Whatever Urban chose to do with his future, he could walk through the world knowing he had his father’s blessing. They never discussed coaching again. Two weeks later, Bud Meyer died in his son’s arms.

Three days after his father’s funeral, five days after his family demanded promises, Meyer accepted the Ohio State job. During his first news conference, he reached into his suit jacket and pulled out a contract written by Nicki, which he’d signed in exchange for his family’s blessing. These rules were supposed to govern his attempt at a new life, as his father’s example had governed his old one. So much was happening at once, and as he said goodbye to the man who molded him, he began undoing part of that molding.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z162832g8xY&w=600]

The contract from his family is incredibly sweet. Perhaps even an example of how what looks like Law (“you must _____”) can actually be an expression of grace and love–and that it can actually be received that way by the person to whom it is directed. This is not a set of threatening rules for Urban to obey or disobey out of a sense of earning, they are a matter of survival. Maybe even a description of the shape a grateful and repentant life might take.

[Urban]’s missed only one or two of Nate’s baseball games since taking the job, an astonishing change. Nicki is entering her final year at Georgia Tech, and her coach scheduled Senior Night on the Saturday of the Buckeyes’ bye week. Urban will walk onto the court with Nicki, a walk he’s made with other people’s children but never with his own. He’s eating, working out, sleeping well, waking early without an alarm clock. On the night before the 2012 Buckeyes gather for the first time, he’s playing catch with his son in Cleveland.

Meyer didn’t just give up a job. He admitted that the world he’d constructed had been fatally flawed, which called into question more than a football career. Follow the dots, from quitting to asking why he’d lost control to trying to understand himself. Who am I? Why am I that way? When the facade fell down, the foundation crumbled too, so he needed more than a relaxing break. If he came back and allowed the rage to consume him again, his quitting would have been meaningless. He didn’t need a piña colada. He needed to rebuild himself. His dad sneered at the weakness when he quit, leveling his stark opinion: “You can’t change your essence.”

In a very real sense, his father was right. The article may need to cast Urban as the hero of his own story, but we know that he’s actually the villain. Or at least, he’s not strictly one of the other. He hasn’t rebuilt himself at all; he’s been deconstructed by success. The school of very hard knocks took him to the end of himself, back to the beginning and back to his senses, where all that’s left are his love of the game and the raw gifts he’s been given. You might say that God’s mercy in Urban’s life has looked a whole lot like a Hammer. And again, it probably isn’t a one-time kind of thing:

On the northwest side of town, Shelley Meyer sits in their new house, praying, literally, that this time will be different. He’s made promises before. She believed his first news conference at Florida in 2004 when he said his priorities were his children, his wife and football — in that order. She believed in 2007 when she told a reporter, “Absolutely there’s a change in him. There’s definitely an exhale.”

She wants to believe today. His willingness to admit the possibility of failure is oddly comforting. He knows he could end up back in 2009, which is worth the chance to reclaim 1986. “There’s a risk,” he says. “What’s the reward? The reward is going back to the real reason I wanted to coach.”

There’s confidence in his voice. She’s heard it, seen how calmly he handled the arrest of two players or his starting running back getting a freak cut on his foot. “Man, I just feel great,” he’ll say.

“But you haven’t played a game yet,” she’ll remind him.

Ohio State did go undefeated this past year. Or so they tell me. And who knows what the cost was. The success might be evidence of rebirth, but it could just as easily indicate relapse. It’s probably some combination of both, as this side of heaven, no one’s life fits completely into a neat narrative of redemption–none of our stories can be reduced to an object lesson, thank God. (Well, maybe One person’s). The hope here is not that Urban will have some kind of unimpeachable change-of-heart testimony that we can all put faith in. The hope is simply that God is merciful, even when his mercy looks like its opposite. The God that Urban has come to know is the God of second chances, third chances, seventy-seventh chances. The one who brings success out of failure and life out of death, the God that, if you’ll excuse the extended metaphor, did not go undefeated. Quite the opposite.

As a concluding postscript, a great little moment of irony and humility (and maybe even a little ‘blessed self-forgetfulness’):

There’s a book [Urban] loves, written for business executives, called “Change or Die,” which shaped his ideas about altering the behavior of athletes. He has talked about the book in speeches, invited the author to Gainesville, handed out copies, and never, not once, did he realize the book almost perfectly described him. In the car on the way to Cleveland, he is read a paragraph from page 150:

“Why do people persist in their self-destructive behavior, ignoring the blatant fact that what they’ve been doing for many years hasn’t solved their problems? They think that they need to do it even more fervently or frequently, as if they were doing the right thing but simply had to try even harder.”

Meyer’s voice changes, grows firmer, louder. “Blatant fact,” he says.

He pauses. A fragmented idea orders itself in his mind. “Wow,” he says.

He asks to hear it again. “Blatant fact,” he says. “It should have my picture. I need to read that to my wife. I’m gonna reread that now. Self-destructive behavior?”

COMMENTS

12 responses to “The Harsh, Hopeful Ballad of Urban Meyer”

Leave a Reply

Thanks Dave. Great piece!

The fact that Bud even reached ambivalence, changing in his own oblique way, was a miracle. He was a hard, hard man. I didn’t read the full article, so I’m not sure if it mentions this. But after Meyer won the 2006 title, as one of the youngest head coaches to do so in college football history, the first thing his dad said to him on the field while the confetti was flying was, “What took you so long?” I believe it was with a straight face.

Homerun, Dave. Or should I say touchdown?