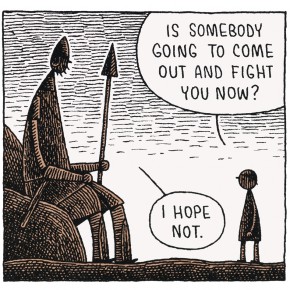

Had the whole David and Goliath showdown happened in the age of Twitter, David may not have won. Here’s how it could have gone down today:

Goliath, after voicing his threats for weeks to the nation of Israel, finally finds his less-than-worthy opponent strut to the battlefield, slingshot in hand, nothing but his ruddy good looks and youthful optimism girding him. He says to Goliath, “I come to you in the Lord of hosts…the Lord will deliver you to my hand and I will strike you down and cut off your head.” Goliath, while not the brightest of the bunch, understands that this is the classic Israelite subversion tactic—the strength of the weak, the righteous anger of the oppressed, yada yada—and so steps back with a subversion tactic of his own. He pulls out his phone, and tweets:

ThePhilistine

@saulgoodisrael what have I ever done to provoke your anger? Shepherd boy bullying about beheading! #YHWHbully #youcometomewithsticks? #philistinestrong

Of course, the Philistines behind ThePhilistine go bananas. They take it global, they make it viral, and before you know it it’s trending. Even Israel’s quick counters can’t undo the rash of infamy they now know. Within minutes, David is not the shepherd-boy-turned-King, the least of these; he is a know-it-all provocateur, making some seriously exclusive truth claims about, let’s face it, some seriously subjective beliefs.

Once a bully, always a bully, David thinks. He sacrifices his political reputation to carry out what God had planned anyway—he fires the stone, Goliath falls. What changes, though, is that Israel wins, but in winning, Israel loses. The defeat of the Philistines provokes an entire planet of #philistinestrong victims. Goliath’s fall was the final subversion tactic, and suddenly Israel becomes the oppressive force it woke up that morning needing protection from.

A stretch? I know, it is, but not by much. So goes the fate of the empowered victim these days, something we’ve talked about quite a bit of late, where the semantics of offense are as available to Flint, Michigan residents as they are to their government officials. In other words, bullies are getting in on the action, too. Heather Havrilesky says as much in her piece in this past Sunday’s NYT Magazine. She describes the blurring lines between power and victimhood, and the ever-alternating roles of bully and bullied.

As the word spreads beyond its original childhood boundaries, it also loses much of its power. Increasingly, “feeling bullied” is used broadly by the powerful and the powerless alike to describe feeling insulted (by a peer), feeling unfairly criticized (by a professional critic), feeling diminished (by commenters) or merely feeling exposed to potential profit losses, ego injuries or points of view that run counter to your own.

This frequent misapplication of the term reflects a larger sea change in the way we view our social positions on an emotional level. These days we tend to see power less as the rightful inheritance of the world’s winners (us!) and more as the end product of a disgraceful cycle of opportunists oppressing their way to the top of the human heap.

Havrilesky is arguing that this opportunism for power is fair game, victim and oppressor alike. In fact, victimhood itself is a way to disrupt that human heap—to pull out the bottom and let the top fall, and begin climbing yourself. And as she notes, in our new digital environs, everyone has a shot at it: “This new order has a way of making us feel more powerful than ever and more powerless than ever in rapid succession.”

But the other point Havrilesky makes is the coercive use of emotion in public spheres. She says a bully has become anyone who makes us “feel insulted/criticized/diminished.” And no one can tell us how we feel—only we know how we feel. Which brings us back to the violence of David and Goliath, two unlikely foes doing battle, except this time not with slingshots and swords, but by the manipulation of their own emotional weaponry. In this battle, the objective foe lives or dies by the use of one’s own subjective word.

This topic of emotional reasoning—and its pervasiveness in American culture—was the focus of another amazing article this past week, written by Molly Worthen (whose name you’ll remember), entitled “Stop Saying ‘I Feel Like’”. Besides feeling a bit pinned to the wall by her diagnosis of the phenomenon, Worthen rightly describes that we say “I feel like…” when we don’t want to be wrong. “I feel like” is a linguistic hedge that protects us from having to put our neck out the way we would if we said “I think.” Sticking with your subjective “feel” allows us to both say anything—to continue our persistent and pervasive opinionating—and say nothing at all.

This topic of emotional reasoning—and its pervasiveness in American culture—was the focus of another amazing article this past week, written by Molly Worthen (whose name you’ll remember), entitled “Stop Saying ‘I Feel Like’”. Besides feeling a bit pinned to the wall by her diagnosis of the phenomenon, Worthen rightly describes that we say “I feel like…” when we don’t want to be wrong. “I feel like” is a linguistic hedge that protects us from having to put our neck out the way we would if we said “I think.” Sticking with your subjective “feel” allows us to both say anything—to continue our persistent and pervasive opinionating—and say nothing at all.

Worthen mentions the pitfalls of these kinds of arguments.

This linguistic hedging is particularly common at universities, where calls for trigger warnings and safe spaces may have eroded students’ inclination to assert or argue. It is safer to merely “feel.” Bradley Campbell, a sociologist at California State University, Los Angeles, was an author of an article about the shift on many campuses from a “culture of dignity,” which celebrates free speech, to a “culture of victimhood” marked by the assumption that “people are so fragile that they can’t hear something offensive,” he told me.

Yet here is the paradox: “I feel like” masquerades as a humble conversational offering, an invitation to share your feelings, too — but the phrase is an absolutist trump card. It halts argument in its tracks.

When people cite feelings or personal experience, “you can’t really refute them with logic, because that would imply they didn’t have that experience, or their experience is less valid,” Ms. Chai told me.

“It’s a way of deflecting, avoiding full engagement with another person or group,” Elisabeth Lasch-Quinn, a historian at Syracuse University, said, “because it puts a shield up immediately. You cannot disagree.”

This isn’t to say that emotions don’t play a heavy role in reasoning. Of course they do. Worthen and Lasch-Quinn are just also saying that ‘I feel like’ conversations play offense by way of defense. Conversations—which are supposed to be made up of argument, confrontation, but most importantly, objective reasoning—are now blunted by our subjective emotions. In our culture of acceptance and inclusion, the validity of our own personal experiences is the best way to never be wrong.

At the same time, Worthen notes, it isn’t just bad conversational practice. It is painfully isolating. If your conversations, and your beliefs, and your identity are solely comprised of the way you experience the world—the way you feel—then your grip on what’s true about life falls victim to the problem of you. You are perfectly protected, and therefore disastrously safe, from solid facts, and even good news.

This is what is most disturbing about “I feel like”: The phrase cripples our range of expression and flattens the complex role that emotions do play in our reasoning. It turns emotion into a cudgel that smashes the distinction — and even in our relativistic age, there remains a distinction — between evidence out in the world and internal sentiments known only to each of us.

“This is speculative, but ‘I feel like’ fits with this general relativism run rampant,” Sally McConnell-Ginet, a linguist at Cornell, suggested. “There are different perspectives, but that doesn’t mean there are not some facts on the ground and things anchoring us.”

For decades, Americans have been in the process of abandoning both the moral strictures of religion and the Enlightenment quest for universal truth in favor of obsessing over their own internal states and well-being. In 1974, the sociologist Richard Sennett worried that “the more a person concentrates on feeling genuinely, rather on the objective content of what is felt, the more subjectivity becomes an end in itself, the less expressive he can be.”

Perhaps you’ve been in a conversation lately where feelings were an end in themselves. It wouldn’t be a surprise if that conversation happened in church, where the therapeutic semantics of self-help and self-care often runs at fever pitch. And of course, who wants to knock feelings? Knocking feelings is like knocking water. We’re made up of feelings. We need feelings. We could all use a therapist, we could all use some self-help, especially this self writing this post. But in a cultural moment such as the one we’re in now, where every voice is crying out to validate the rightness of their own vague personal perspective, the power of an objective word—spoken over the masses of bully cries and victim pleas—sounds like the best news there is. Something that is true, whether I am feeling it or not feeling it, whether I am defending it or not, whether I am experiencing it or not. I am fickle. I need more than personal experience. A life of total interiority, to me, sounds like hell. I need someone else to tell me what’s true.

Thankfully, this is the (subjective) power of an objective gospel. That while Goliath is tweeting hate crimes, David has been spoken over. That while we tear apart Christ’s clothes at the foot of the cross, he speaks over us, “Forgive them, they don’t know what they’re doing.”

COMMENTS

12 responses to “Subjective Sovereignty and the Need for an Objective Gospel”

Leave a Reply

This was so refreshing to read, thanks. The object of discussion in political and cultural disputes, or so it seems, is never rational persuasion any more, much less mutual understanding first, if in fact it ever was. Instead it’s moral bullying: you hurt my feelings, so you done me wrong, and so your position is wrong, period, end of discussion. Now give me recompense. (I’m searching my heart to see if I do the same thing, but so far I’m not seeing it. You may need to write another post!)

As someone who on most hot button issues is somewhere in the vanishing middle, someone who really wants to hear all sides of a debate – probably as much for fun as for fairness – I find this so depressing. So again, thanks.

So great Ethan! And so true! Part of the conversation I’ve been wrestling with is my own ability to “feel wrongly.” As in, I can have incorrect feelings about a situation, and that third step of analyzing my own emotions (with some hindsight) helps me react better. Which makes it hard, because then I know others can feel incorrectly too. So I totally steamroll over their perhaps legitimate fears/angers/anxieties. I can’t win- ha!

I feel like this was a really good article, Ethan.

Interiority?? Googled it to see if you made up that wonderfully descriptive word. It’s in there – so, looks like someone else made it up! Such a fitting word to describe a life bent in on itself.

This is what I wake up to every morning as I prepare my single cup of pour over coffee. A focus on Me, Myself and I is the start to a perfect day of a living hell. Not to mention others who have to live with me on a daily basis.

So, thank you for another insightful Mbird reminder of our seriously messed up human condition. And, the good news of a Savior who graciously sets us free us from our interiority so we can better love, serve and sometimes even enjoy those who otherwise would be in our way.

Blair

A very nicely written and thought provoking article, I thank you. One small note.

The “I feel” as opposed to “I think” may be an effective linguistic maneuver by some, but in truth it is reflective of the way many people comprehend their world. Myers and Briggs documented the decision making / analytical / judgmental function (Thinking versus Feeling) many years ago, based on Jung’s early work. The implication of the imperative to abandon “I Feel That” is that Feeling is a less valid way of approaching the world. I disagree. If one believes that the I Feel argument creates an absolute barrier to discussion (as strong Thinkers would) or on the other hand that the Rules are Rules and Facts are Facts argument creates a no-use-even-talking situation (as strong Feelers would conclude) isn’t it a more valid approach to try to understand the other party’s argument on its own terms and deal with each aspect of the argument on its own — fact by fact for the Thinker, and Issue by issue for the Feeler?

By taking the discussion to common ground, one can quickly determine whether the other person is merely a skilled debater trying to neuter your argument, or is instead genuinely coming at the problem with a different perspective.

Michael, thanks for the comment. Really interesting thought. As a “feeler” myself, I agree with you that approaching the world happens differently for different personality “types”. And I think you’re right that some people are less wired to make objective fact statements than others. I don’t think that that’s what Worthen is necessarily getting at here, though. She’s pretty clear that emotions influence our decision-making, whether we are “thinkers” or “feelers”. What she’s noticing, instead, is how “I feel like” has become an argumentative pawn–a lazy, relativistic way of stating an opinion without necessarily knowing much about what we’re talking about. I think Worthen is saying that there is such thing as objective truth, and that needn’t be something we should run from.