Grateful for this post from Lisa Cooper:

For by works of the law no human being will be justified in his sight, since through the law comes knowledge of sin. (Rom 3:20)

If you had asked me as a fourteen-year-old where I was destined to be after I died — Heaven or Hell? — I would have told you with relative certainty: “Hell.”

It’s not that I was a particularly bad kid by any obvious standard. In fact, on the surface I looked pretty okay. Success in school came easily to me, I had some friends, and I wasn’t making terrible decisions with radical consequences. But the feeling of disconnection from God was palpable for me, and there was no discernible way out.

I had grown up in the church, at least tangentially. I knew that God existed, or at least probably did. If He did exist, I was certain that this God couldn’t possibly care about me. I could see all around me the effects of sin: broken families, pervasive mental health issues, abuse, anger — seeing all of this amounted to a distinct feeling of restlessness and despair. But I could not, as far as I could tell, impact or change anything. The condition of the world was simply unjust and fraught with problems.

It didn’t help my despondency that my high school had intensive existentialist and nihilist curriculums in freshman, sophomore, and junior year English classes. We regularly read gut-wrenching literature, in which life had little significance and even less hope. By the time I arrived in junior English (I was sixteen at the time) and began reading Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky, I was primed for more sad literature.

Just prior to this, my mother had revitalized her commitment to the local Episcopal church after years of shoddy attendance. She began singing in the praise band and would bring me when I was with her for the weekend. She urged me to begin confirmation class to learn about the faith. I, very hesitantly, agreed. In these confirmation classes, we had to read the book of Luke and study the ecumenical creeds with a mentor.

God orchestrated my repentance and salvation through the study of two books: Crime and Punishment and the Gospel of Luke. Through these two texts, God’s law and the gospel became real for me.

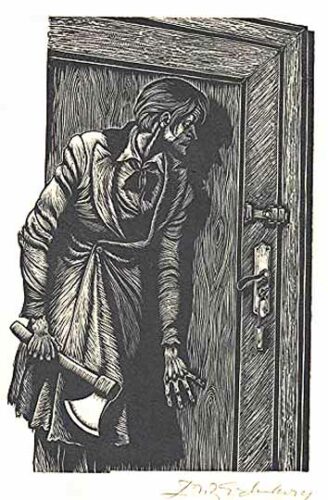

Raskolnikov, the main character in Crime and Punishment, is a former university student who is struggling to pay his bills. His financial destitution is described in great detail. Stemming from his need for money, he begins to wrestle with a philosophy of utilitarianism. Wasn’t he more useful to society than an old woman who pawned items for a living? Could he therefore act toward a higher good based on his own felt needs, even if it meant he would carry out a murder? Raskolnikov, an intellectual, identifies himself as a man of a higher echelon, a man who could act on noble principles without consequence. This is how he decides that he can morally murder an old woman, Alyona Ivanova, and take her money.

All of this is important groundwork for the book’s pivotal scene where he carries out the murder and tries to escape. This is the scene I was reading when I finally realized I was a sinner.

Raskolnikov, in a fit of delirium, fumbles to latch Alyona Ivanova’s door. Both she and her half-sister Lizaveta are dead by his hand, lying on the floor in a pool of blood. He busies himself washing the murder weapon in the sink, until he hears a knock at the door. Someone is looking for the old woman. More knocks at the door sound, and Raskolnikov can hear the man shouting for Alyona to open up.

With great strength, the visitor shakes the door. Another man arrives looking for Alyona and suspects something strange is happening. Curious — the apartment door is locked from the inside. She must be home! Turning away, the two men seek the building caretaker to open the door. In that opportune moment, Raskolnikov slips through the door to the stairwell.

Then, the most unnerving of scenes: In order to exit the building, Raskolnikov has to descend four long flights of stairs that lead past the caretaker’s office. He has to pass the men who have come looking for Alyona, giving himself away as the murderer.

Traveling down the stairs, he can hear their voices getting closer. He will be confronted soon, but at the very last second he ducks into an open apartment and remains undetected by the men on the stairs.

Reading this scene, I found myself hoping, wishing, that he would make it out of the building without being discovered. My heart was racing in anticipation of his encounter with the men on the stairs, and I was so relieved when he found a hiding place. It was in that moment that I became aware of myself. A sick feeling overcame me: I wanted a murderer to escape! What is wrong with me?

I suspect many consecutive years of reading existentialist and nihilistic literature prepared me to feel the movement of this story so deeply. I felt his frustration. With no clear right and wrong, and a bent toward intellectualism, so much evil could be excused or explained away. All of this is to say, I realized along with this scene that I had no actual reason to think murder was wrong, yet I was still confronted with how wrong it felt.

By the grace of God, I was reading the Gospel of Luke at the same time. My eyes had been opened to the reality that the world around me was not only deeply wrong, but I myself was sinful. It was not a week later that I heard the words of Jesus, “I have not come to call the righteous, but sinners to repentance” (Lk 5:32).

Jesus was calling me, a sinner, to Himself. Not because I was righteous but precisely because I was not. We studied the Nicene Creed: “Who for us men and for our salvation came down from heaven,” and, “He was crucified for us under Pontius Pilate.” For us. He did these things for us — for me.

It had always confused me how a man’s death over 2,000 years ago could have any relevance to me or to my eternal state. It was not until I learned about what theologians call the “great exchange” that I finally understood. Jesus merited eternal life by fulfilling God’s law perfectly, something I could never do. By dying in my place, he paid my debt in full, and by rising from the dead, he has secured for me eternal life. Death itself has been defeated.

The Gospel of Luke and Crime and Punishment bear striking connections. While Raskolnikov sought money and was willing to murder for it, Jesus was also given over to death by a selfish man, Judas, who wanted money. Jesus’s place on the cross was originally meant for a murderer named Barabbas. Jesus literally took the place of this murderer and suffered the same death penalty, but he had done nothing wrong.

I could no longer bear the weight of my own sin. I identified with Raskolnikov. I could continue to try to explain away my sin, or I could confess and look toward Jesus for salvation. As Simon Peter confesses in John 6:68, “Lord, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life.”

COMMENTS

4 responses to “Experiencing Law and Gospel Through Dostoevsky and Jesus”

Leave a Reply

Excellent, Lisa! Mbird, more from this writer please 🙂

A beautiful testimony of God’s grace at work in your heart Lisa – Thank you for this!!

Lisa- this is wonderful. As far as I’m concerned, nobody has a better answer to the problem of evil than FD. I once heard a speaker say that, at the end of the day, there are only two satisfying answers to the problem of the human condition – it’s either Nietzsche or Dostoyevsky – and I think I agree with that. I’ve read Crime and Punishment and Brothers Karamazov, and I have started twice on The Idiot but have stalled out each time. Yada yada, glad to hear others are having the same revelatory experiences with FD that I’ve had. The man is truly a genius.

Well written, insightful, and helpful. Thank you, Lisa. Continue writing, you are a true gift to the church and society