Another glimpse into the newest magazine. Order up: they’re going quick!

Rare is the 6-year-old kid who, if asked what job they’d like to have when they’re older, would answer “psychologist.” Astronaut or movie star perhaps, but headshrinker? Very few kids even know what the word means! Dr. Harriet Lerner is not your average bear. She’s had her eye on the prize since kindergarten (in 1950), and is now counted as one of America’s most respected experts on the psychology of women and family relationships.

Rare is the 6-year-old kid who, if asked what job they’d like to have when they’re older, would answer “psychologist.” Astronaut or movie star perhaps, but headshrinker? Very few kids even know what the word means! Dr. Harriet Lerner is not your average bear. She’s had her eye on the prize since kindergarten (in 1950), and is now counted as one of America’s most respected experts on the psychology of women and family relationships.

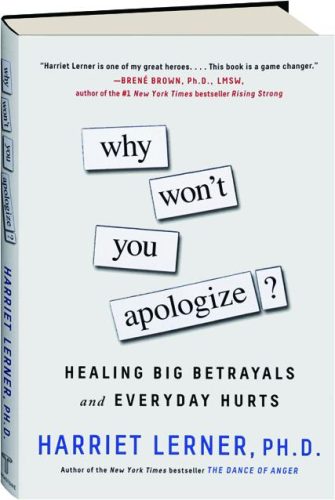

Dr. Lerner first made a splash back in 1985 with the publication of The Dance of Anger, which went on to sell three million copies. Since then, she has blessed us with nine more books, the most recent being Why Won’t You Apologize?, an indispensable and highly accessible volume that profiles the many strategies and self-deceptions we employ around wrongdoing—on what counts as an apology, and on what keeps us from giving (and receiving) one. Needless to say, it’s a goldmine of pastoral wisdom—a must for anyone interested in the practical dynamics of reconciliation and repentance. Of course, any book with blurbs from Anne Lamott, Brené Brown, and Esther Perel hardly needs an additional thumbs-up from us! We were so honored that she agreed to answer some questions for us.

You begin your book Why Won’t You Apologize? by talking about all the caveats we clip on the back end of our apologies, and how these caveats totally undo the apology itself. (“I’m sorry you feel that way,” “I’m sorry if …,” “I’m sorry, but you have to understand …”) Are people hardwired to have certain favorites?

I don’t think so. When it comes to mucking up the apology, people are more alike than different. We’re wired for defensiveness, to protect our favored image of ourselves. Every single one of us has certain relationships and particular circumstances in which we are apology-challenged. None of us is immune from slipping into vague, obfuscating language that obscures what we are sorry for.

Are there apologies that are particularly challenging for you?

One of the quirks I share with my husband is that I like to apologize for exactly my share of the problem—as I calculate it, of course—and I expect him to apologize for his share, also as I calculate it. We don’t always do the same math, which can easily lead to the theater of the absurd.

I also have a tough time apologizing when the person who is criticizing me can’t see their own contribution to the problem, and when I think their feelings seem exaggerated or off the mark. It’s not easy for me to focus exclusively on the hurt feelings of the other person, apologize for my part, and let go of my strong wish for the other person to see things my way. I’m still working on it.

Why do we have these caveats? Why is it so hard to own up to wrongdoing?

Like I said, humans are wired for defensiveness. It’s easy to apologize for a small matter like spilling red wine on a friend’s carpet. But when someone is confronting us with how we’ve inflicted a larger injury, we immediately go into defensive mode.

When we listen defensively, we automatically focus on the exaggerations, distortions, and inaccuracies that indeed may be there, rather than listening for the essence of what the hurt or angry party needs us to understand. Then we tend to swing into debate mode to correct the facts and make our case.

It’s challenging to practice listening only for the part we can agree with, and to apologize for that first. We can always have a second conversation in which we share how we see it differently.

If only we would listen with the same passion we feel about being heard.

While these dynamics happen everywhere, it’s pretty obvious that apologies are most difficult with those closest to us—our immediate families.

It’s in our most enduring and important relationships that we are least likely to be our best selves. In marriage or couple relationships, for example, there may be little agreement on who started it, who is to blame, and who needs to apologize first.

Of course, the real question is not who started it, or who is to blame, but rather what each person can do to de-escalate the situation. It takes only one person to offer the olive branch and the other to accept it, but in family life people get stuck in entrenched patterns where we lose the ability to think creatively about how to calm things down. Each person wants change, but no one wants to change first.

What’s the hardest part of a good apology for a serious offense?

The biggest challenge is to dial down our defensiveness and to listen with an open heart to what we don’t want to hear. Listening is everything.

It’s not the words “I’m sorry” that soothe the other person and make the relationship safe again. More than anything, the hurt party wants to know that we really “get it,” that our empathy and remorse are genuine, that their feelings make sense, that we will carry some of the pain we’ve caused, and that we will do our best to make sure there is no repeat performance.

There is no challenge greater than listening to the anger and pain of someone who is accusing us of causing it, especially if they can’t see their part.

You say that some people will never apologize. And that it’s much harder to apologize for inflicting a big injury than a small one.

People who commit serious harm may never get to the point where they can admit to their harmful actions, much less apologize and aim to repair them. Their shame (or rather their need to avoid collapsing into shame) leads to denial and self-deception that override their ability to orient to reality.

In other words, the non-apologizer walks on a tightrope of defensiveness above a huge canyon of low self-esteem. And no person can be more honest with us than they can be with their own self. If you plan to open up a difficult conversation with a family member who has hurt you, do so because this is the ground you want to stand on, and because you need to hear the sound of your own voice saying what you know to be true. Understand that the apology you long for and deserve may not be forthcoming, not now or ever.

You mention that forgiveness isn’t always necessary or a good thing.

In my book Why Won’t You Apologize? I have a chapter called “‘You Need To Forgive’ And Other Lies That Hurt You.” There’s a lot out there suggesting that forgiveness is the only path to a life that’s not mired down in bitterness and hate, and that those who do not forgive the non-apologetic offender are at higher risk for both mental and physical problems. This is simply not true.

You do not need to forgive a non-repentant wrongdoer who hasn’t earned your forgiveness. And in encouraging a friend or family member to forgive (“Your father was abused himself, and he did the best he could”), we may leave the hurt or traumatized person feeling alone, disoriented, and abandoned all over again.

You do not need to forgive someone who has never apologized, listened to your feelings, or taken responsibility for what they did (or failed to do). You do need to find a way to let go of the corrosive aspects of anger and pain that only serve to keep you stuck. As I explain in Why Won’t You Apologize?, letting go and finding peace does not require forgiveness.

Okay, so we know how we tend to muck up the apology. What makes for a good one?

In a good apology we take clear and specific responsibility for what we have said or done—or not said or done—without a hint of evasion, blaming, obfuscation, or excuse-making, and without bringing up the other person’s crime sheet.

We listen carefully to the hurt party’s anger or pain, without interrupting and saying things that make the hurt party feel unheard or cut short. We do our best to ensure that there is no repeat performance.

Because we’re all imperfect human beings, prone to error and defensiveness, the challenge of offering a heartfelt apology is with us until our very last breath. It’s difficult and it’s worth it. All of your relationships—especially your relationship with your own self—will benefit from your efforts.

COMMENTS

5 responses to “The Art of a Good Apology: Our Q&A with Harriet Lerner”

Leave a Reply

This is found towards the end of the article: “You do not need to forgive a non-repentant wrongdoer who hasn’t earned your forgiveness.” I would appreciate additional analysis of and opinions about this statement.

Fisherman, thanks for your comment. Harriet isn’t claiming to come from a Christian perspective on forgiveness. But, at least to this reader, I do think she’s coming from an understanding of human limitations when it comes to forgiveness: mainly that some hurts and betrayals are too big for us—or too damaging—to get there alone, and we shouldn’t feel bad if we can’t get there. Dr. Lerner doesn’t say this, but I personally believe that these are the ones we give to God, who can (and has) blotted out much more than we ever could.

Ethan, that was very well stated.

As I read this interview, I found myself furrowing my brow a bit.

I suspect that the “non-apologetic offender” presents us with our abiding limitations in the realm of forgiveness, as well as the full offense of the prayer “forgive us our trespasses as we forgive…”

I have found myself suggesting to people – people who have endured deeply hurtful offenses – that they pray for God to forgive that offender. And then they might pray for God to work forgiveness in their own selves, over time.

One might want to do this, not in order to avoid a “a life …mired down in bitterness and hate” but simply to live in alignment with the Lord’s Prayer.

This is not easy stuff of course, if it were, we might suggest that there would be no need for the cross.

Of course, any book with blurbs from Anne Lamott, Brené Brown, and Esther Perel hardly needs an additional thumbs-up from us! All truth is from God . Certainly these three ladies provide valuable insight and wisdom. As Mockingbird is a Christian organization, some perhaps ” soft disclaimer “, that these three are not coming from a Christian world view , might prove helpful . Thank you .

[…] mbird.com/2019/07/the-art-of-a-good-apology-our-qa-with-harriet-lerner/ […]