Grateful for this write-up on the new Fred Rogers documentary, opening in theaters this month! By our friend Mike Cosper:

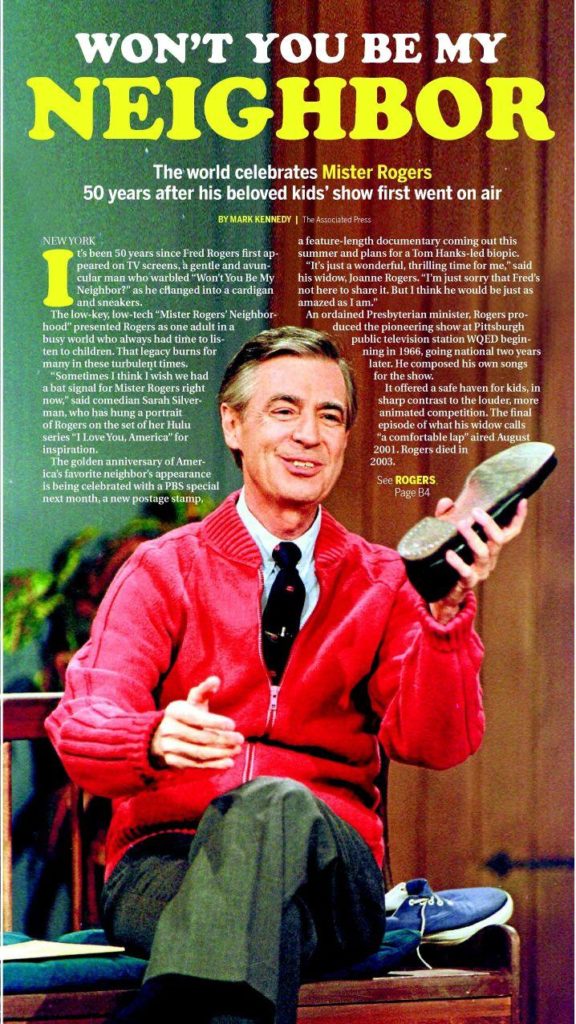

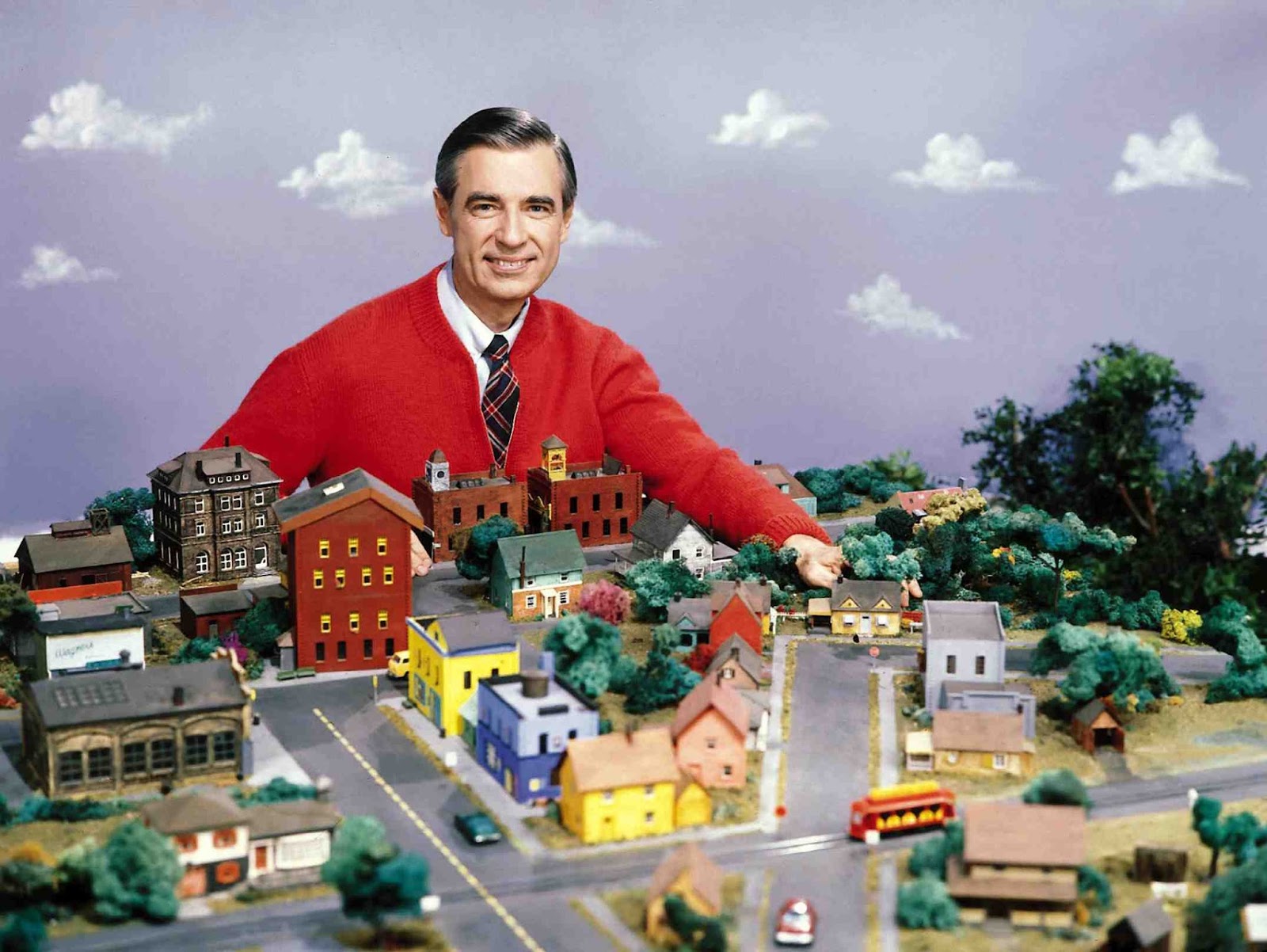

One of the achievements of Morgan Neville’s new documentary, Won’t You Be My Neighbor, is the profound contrast he’s able to demonstrate between the world of Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood and the rest of children’s entertainment.

One of the achievements of Morgan Neville’s new documentary, Won’t You Be My Neighbor, is the profound contrast he’s able to demonstrate between the world of Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood and the rest of children’s entertainment.

We’re shown clowns being pounded in the face with pies, gun-wielding Transformers and grenade-throwing GI Joes, and (perhaps the most serious offenders) Ren and Stimpy committing various acts of violence upon one another. Then we see Fred Rogers, speaking gently and slowly into the camera, entertaining with crude puppets and toys, singing simple songs about the fears, questions, and feelings that are central to the experience of childhood. In one of the few moments where we see Fred angry, he says, “I’ll tell you what children need.” They need what he gave them: a sense of presence, stability, and love. Not more of the world’s violence and chaos.

Fred was an ordained minister in the Prebysterian Church of the USA, and his ordination specifically called him to work and minister through television. That’s the way he always understood his work: as ministry. Mr. Rogers looked at us through our TV screens to tell us we were children of God, worthy of dignity, worthy of loving and being loved. When segregationists poured bleach into public swimming pools with African Americans in them, Fred Rogers shared a cooling foot bath with his black neighbor. When the world was reeling from the assassination of Robert Kennedy, Daniel Striped Tiger was teaching us how to grieve and how to express fear. He was there for us after the Challenger Space Shuttle explosion, and he came back to television after 9/11 to speak once again about fear, grief, and human dignity.

The film is incredibly moving, both because Neville’s storytelling and pacing is executed beautifully and because almost everyone in the audience comes into the theater with a deep attachment to Mr. Rogers. His direct-to-camera speech made us feel like he really saw us, and his sensitivity to the needs and fears of children made us feel like we were understood. We weren’t trivialized. We weren’t dismissed.

None of this was by accident. Rogers had a deep conviction and a sense of moral clarity about his work. In 1969, $20 million of federal funds were threatened by budget cuts, and Rogers went to the Senate to advocate for PBS. The senator leading the charge on the cuts was John O. Pastore, a gruff, hostile character who seemed to have already made up his mind before the hearings began.

Rogers didn’t make political arguments, though. Instead, he talked about the importance of his work: “I give an expression of care every day, to each child, to help him realize that he is unique. I end the program by saying, ‘You’ve made this day a special day, by just your being you. There’s no person in the whole world like you, and I like you, just the way you are.’ And I feel that if we in public television can only make it clear that feelings are mentionable and manageable, we will have done a great service for mental health.”

Then, in a breathtaking move, Rogers asked if he can recite the words to one of his songs. Pastore allowed it, and Rogers said:

What do you do with the mad that you feel? When you feel so mad you could bite. When the whole wide world seems oh so wrong, and nothing you do seems very right. What do you do? Do you punch a bag? Do you pound some clay or some dough? Do you round up friends for a game of tag or see how fast you go? It’s great to be able to stop when you’ve planned the thing that’s wrong. And be able to do something else instead ― and think this song ―

“I can stop when I want to. Can stop when I wish. Can stop, stop, stop anytime… And what a good feeling to feel like this! And know that the feeling is really mine. Know that there’s something deep inside that helps us become what we can. For a girl can be someday a lady, and a boy can be someday a man.”

Pastore leaned back in his chair, clearly moved. “I’m supposed to be a pretty tough guy and this is the first time I’ve had goosebumps in two days,” he said. “Looks like you just earned your $20 million.”

It was a clash Rogers should have lost. Everything about the circumstances were set against him — the toxic politics of the Vietnam war, the hostility of conservatives towards PBS, even the physical arrangements of the Senate subcommittee’s chamber, where the Senators sit high above those giving testimony, and where Rogers surely felt overwhelmed and easily dismissed. But his peculiar charisma won the day. In a moment that shouldn’t really surprise people of faith, something small, meek, earnest, and rooted in love won out in a conflict with power.

There’s a sad note to the documentary, though. Work like Rogers’ is rare, as are so many of the things that are good for our souls. And though several generations grew up with Rogers as a fixture in their homes, our culture as a whole seems to be just as toxic as it ever was. Entertainment just as vapid; politics just as hate-filled. Rogers’ place in history is that of a strange, beloved prophet who preached kindness and dignity while the world around him burned.

It’s actually no wonder that we have such a hard time accepting Rogers’ message. It’s core message is as controversial as the gospel itself — that we are God’s children, innately worthy of loving and being loved. But we don’t want innate worthiness; we want achievement. We want to have earned our worth. Consciously or not, we resist that good news and find ourselves either striving for worthiness, creating the hostile and competitive aspects of our culture — or numbing ourselves, creating the loud and distracting aspects. Both are dehumanizing. Both are draining. And we cling to them for dear life.

In one moment, Won’t You Be My Neighbor, throws this reality into the spotlight. On a segment of Fox and Friends, the hosts blame Mr. Rogers for a “culture of entitlement.” One of them actually refers to Rogers as an “evil, evil man.” He’s ruined a generation, they say, because he told them they were special apart from any of their achievements. It’s the one moment of the film where we get to see any real villainy. But I also think it exposes the ugly underbelly of the law-loving human consciousness. Don’t gift me with worthiness…make me earn it…and I’ll make you earn it, too.

Alternatively, to embrace the message that we are worthy of love, just as we are, brings us face-to-face with our flaws. We immediately feel our unworthiness and our shame. This is precisely what makes Rogers’ show so brilliant. He was just as invested in helping children articulate their negative emotions as he was in affirming their inherent value as unique and special persons. He empowered children to talk about their sadness and their fears, because doing so is a necessary part of embracing and being embraced by love. Expressing our vulnerable emotions invites intimacy.

Denying them leads to secondary emotions like anger and rage, both of which are expressions of power meant to insulate us from the world. They create distance, and that distance provides an illusion of safety. This, of course, is why there is so much anger in our culture. We’ve repressed all of our vulnerable emotions like sadness, fear, and grief, and that repression wells up into rage, lashing out at whatever scapegoat it can find. And while I’m sure most of us would agree that there must be a better way, we’re not willing to pay the price of vulnerability to get there. We’d rather be angry; we’d rather be distracted.

This is precisely why Fred Rogers stands out so starkly in our world, even today. Here was someone who truly believed he was loved and embraced by God, so much so that he was comfortable sharing his vulnerabilities with children, with neighbors, and with Senators. The Fred Rogers we discover in this documentary is utterly consistent on and off the screen. Every life he seems to have encountered was left a little brighter, a little warmer for his presence.

It reminds me of the life of Jesus in the Gospels. Everywhere he goes, death and decay move backwards. Disease vanishes. Dead people are raised. Demons flee. I have this image that’s been in my mind for years, imagining that with every step, the ground under Jesus’ feet blossomed into life. It’s an image of the Kingdom of God advancing into a darkened world.

Fred Rogers lived that way. Life flourished around him. Darkness fled. He was a man empowered with the good news that God loves us and thinks we are utterly worthy of love, and that message was, is, and always has been, revolutionary.

COMMENTS

7 responses to “The Revolutionary Message of Won’t You Be My Neighbor”

Leave a Reply

Full disclosure – I was NEVER a fan, and I feel like he’s much more popular in posthumous status (but maybe that’s the point).

I was maybe 8 when he started on PBS, but I always thought he was boring, so I never made it required viewing for our kids when they were young. That’s a big fail on my part. Here’s to the parents and kids who jumped on the Rogers Choo-choo way before most of us.

I think if you actually listen to what was said on Fox and Friends it not nearly as bad as all that. I believe it was a professor complaining about kids feeling entitled to A grades just because they are special……( and they aren’t )…..

If that’s true, then it makes little sense why Mr. Rogers would be the target of their ire. Unless, perhaps, they were willfully misinterpreting his message to exploit this particular situation, and thereby make a broader argument that people ought to ‘earn’ their worth, as the author said above. Either way, their statements are absurd and come off terribly.

Thanks for the article, Mr. Casper. I thought the documentary was excellent as well.

you can search and watch the actual clip

It’s complicated https://savedbydesign.wordpress.com/2018/02/20/mr-rogers-is-not-jesus/