This post comes from new contributor Elsa Wilson:

“Films can heal,” said German director Wim Wenders when asked about his recent documentary The Salt of the Earth (2014). The Oscar-nominated film sears us with starvation, disease, and separation, and yet ends with hope restored. How? Wenders’s film embodies the process of healing with three big ideas: dislocation, transcendence, and grace. This isn’t the first time Wenders has used these ideas to give hope to the characters and settings of his films.

The Salt of the Earth might function as a microcosm of Wenders’s overarching artistic pathos. The driving forces of the documentary – despair turned to hope, hurt turned to healing – especially echo Wenders’s earlier film Paris, Texas (1984).

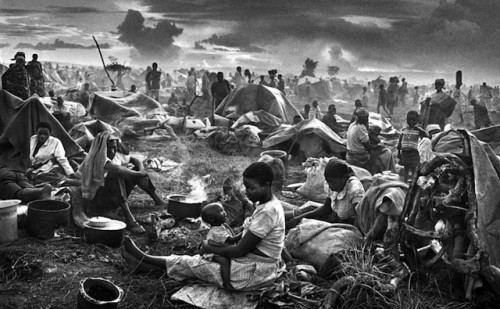

The Salt of the Earth follows Brazilian photographer Sebastião Salgado’s global pursuit of compelling images and stories. His photo projects take him from the gold mines of his native country to post-genocide refugee camps in Rwanda. Although Salgado narrates most of the film, Wenders’s vision for and attraction to the content shape our reception of the story. Salgado was entranced by the sense of dislocation in the people he photographed, and Wenders in turn reveals this dislocation to the viewer. Near the beginning of the film, Salgado says that photography is “writing and rewriting the world with light and shadows.” Wenders seems to make The Salt of the Earth as a continuation of his other films, in that it shows how cinema can rewrite the world. Wenders “writes” the world of dislocation and suffering, coming out of his own search for identity in post-war Europe. Like Salgado, he presents what he sees in the world – he acknowledges what is. But he also rewrites how we see the world. He doesn’t end the story with suffering. He bears testament to the hope Salgado discovers. Salgado channeled his heartache into an environmental project, and that’s where Wenders ends his documentary – with the camera panning through a reclaimed rainforest. The Salt of the Earth begins with death and ends with life. In its own way, Paris, Texas follows a similar redemptive path.

Wenders makes films that embody the hope of healing “not the world, of course,” but “our vision of it, and that’s already enough.” But before his films can “write” the healing, they must write the wound. Wenders sets his films where we are. Wenders says that the modern world suffers from “dislocation.” Dislocation can be defined in this context as a sense of being where we are instead of a better place we could be. Dislocation underlies the human anguish that Salgado and Wenders capture.

Salgado journeys to places where hope has shriveled. The harsh desert setting in Paris, Texas provides a physical counterpart to this hopelessness. The opening shot finds the protagonist Travis in a parched landscape, looking for water. Travis is a dejected, dislocated wanderer – far from men and far from God. Travis’s wife Jane is trapped in mental instability and fear, alienated from her son and her husband. Salgado echoes this alienation when faced with the destruction happening around him. Some of the most disheartening observations Salgado makes are of humans trying to save themselves through pursuits of wealth or dominance, and miserably failing. The loss of hope that results is where his personal “dislocation” comes from. Salgado doesn’t know where to turn after finding his destinations desolate. “When I finished my work in Africa,” Salgado says, “I became very sick. I stopped photography. My health was not good. Not that I caught a disease, but I saw so much distress there. So much violence, so much brutality. I felt that my own body was starting to die.”

The source of our dislocation can be glimpsed in the formal aspects of Wenders’s films. In Paris, Texas, the scene when Travis is finally reunited with his estranged wife happens with a one-way mirror between them. Travis’s reflection is superimposed onto hers, showing how his mistakes have hurt her. A similar technique is used in The Salt of the Earth, when Salgado describes the desperation he saw. As he narrates, his face is superimposed on the photograph of a despondent miner. We see just how much the evil has affected him, as the suffering is literally translated onto his face. But his face on the photograph means something more. Not only is the photo on him – not only is the horror on him – he is on the photo, he is on the horror. This seems to partly reflect Salgado’s own moral degeneracy. Whether or not Wenders believes humans are inherently fallen, his work paints humans as inherently weak. Superimposing Salgado’s face on the desperate scene could be a way of visually marking where his ability ends. He watches evil happen, but he can’t stop it. “People are the salt of the earth,” says Wenders in the documentary’s opening. People are the ones giving the earth its flavor, and the flavor is often terrible. Wenders seems to wonder if we are all guilty, or at least tragically incapable, of something.

As an artist, Salgado’s response to his observation defines him. His face superimposed on the photo means he is participating in that world. He chooses to tell those stories. He listens to the sufferers, and asks us to listen as well. Wenders joins his cause, retelling the photographed stories in the larger narrative of Salgado’s own life story. Wenders and Salgado “rewrite” the world by giving their unlikely characters the opportunity to be heard. Because photos and films expand the life of their subjects beyond geographical and temporal location, the people in them receive a presence in the world that they wouldn’t otherwise have. In a way, Wenders and Salgado give their characters a second chance each time their photos or films are seen.

Part of Salgado’s response to the darkness he photographed is to realize that someone or something else must intervene. Emotionally exhausted, he recognizes he can go no further on his present strength. After photographing a nightmarish Rwanda, Salgado asks, “What is there to do now?” He puts down his camera.

As dislocated people, Wenders said that we suffer from “worldwide homesickness.” Dislocation and homesickness imply a home and a location somewhere in the past that has since been lost. The search for these lost places is where Wenders’s themes function in a restorative sense of redemption. Wenders portrays where we are and then, like Salgado, searches for where we need to be. Wenders said that a responsibility of the filmmaker is to refresh and relieve the world from “worn out images.” We need something more than what we have, and Wenders points to that.

Wenders’s focus on healing touches multiple aspects of dislocation, transcendence and grace. He begins with where we are, moves on to where we need to be, and leaves us with a glimpse of how to get there. In part, The Salt of the Earth is about giving sufferers a space to be seen, articulating their pain on their behalf. That’s Salgado’s way of showing kindness: taking pictures of “the least of these” when no one else cared. He can’t save them by taking their pictures, but his attention to their struggle and his desire to remember them echoes the One who can.

The Salt of the Earth and Paris, Texas are about Wenders pulling hurting people out of the shadows. Like Salgado, his work gives voices to those weary of crying out. By showing the sufferers to us, Wenders makes us aware of their need to be healed. He demonstrates that Salgado and the images he photographed are valuable enough to have their stories told. He tells stories even when they are ugly. Maybe he even gives value to those the world scorned, echoing the incomprehensibly ultimate grace that God gives to us. Wenders can’t really reclaim these people from their circumstances. But he does confirm a presence for the arts in places where hope can heal the hopeless.

We must be shown moments of grace before we can show them to others. Travis could not have shown kindness and forgiveness (two essential characteristics of grace) to Jane if his brother had not shown kindness and forgiveness to him first. Salgado hints at a similar co-dependence for artists. “When you take a portrait,” says Salgado, “it’s not just yours, they’re offering it to you.” Wenders presents a beautiful, but limited, picture of darkness turning to light. The real power of God’s grace is that it doesn’t depend on anyone or anything.

When we are offered clarity enough to see the depths of our dislocation, we cannot help but yearn for a way home. We are then freed to search for that location which we are dislocated from. This “being on the road,” Wenders says, can be “a state of grace” – a movement toward somewhere better.

After years of alienation, Travis and Jane reunite in a dark room. They can’t see each other until they discover how to turn the lights on. The German poet Rilke says that grace in art happens when “suddenly one gets the right eyes.” That pursuit of the “right eyes” is Wenders’s response to a suffering world, and his attempt to change our perspective.

Once we realize we need something else, we can look for it. That “something else” could be divine compassion breaking into our souls and worlds. Wenders’s films pursue life after death, at least metaphorically. After Rwanda, Salgado asked “what next?” His answer was a project called “Genesis.” Salgado channeled despair into replanting a rainforest in Brazil. Here, Wenders shows a physical manifestation of redemption: reclaiming natural beauty out of destruction. This ecological reconstruction evokes a greater spiritual restoration. Salgado discovered hope when he saw a little bit of rainforest growing back on its own. His eyes were opened, and he couldn’t help but watch it change his life. Salgado and Wenders respond to hope in ways that seem less about human initiative, and more about awe.

His perception of restoration allows Wenders to make what he calls “vertical road movie[s]” – ways for the healing grace of heaven to reach the broken throes of earth. Travis began as a wanderer, looking for water, unable to return home. He ends up restoring his family. Travis receives the unconditional kindness of his brother, is transformed by it, and then shows kindness in turn. He isn’t heroic by his own merit. He’s saved by something beyond him.

“Maybe eternity is measurable,” says Salgado near the end of The Salt of the Earth. Maybe it’s measured in how we perceive each moment. Rilke says that art is about learning “how to see.” If we watch films hoping to see better, then we can, as Wenders promises, “walk out of a theater and see the whole world with different eyes.” Only then can our wounds start to heal, because we see that someone else must heal them.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply