Now that Friday Night Lights is off the air, there’s really only one contender for the best drama on television: Breaking Bad, obviously. But Breaking Bad is more than just a successor to the breadbowl-drama throne. It is the Old Testament to Friday Night Lights’ New Testament. Or maybe, the Old Covenant to FNL’s New Covenant. Law to its Gospel. Wrath to its Mercy. You get the drift – where Friday Night Lights locates grace in defeat, Breaking Bad is more interested in the consequences of victory and the cost of glory. What looks like the ascendency of Walter White, from lowly chemistry teacher to millionaire crystal-meth crimelord, is actually his demise, and as viewers, we get treated to all the fascinating gray (rest-)areas on his personal road to perdition.

A lot of shows that depict such blindingly dark subject matter (and radically low views of human nature) get painted with the nihilistic brush, with morality cast as a noble but ultimately quaint distraction from reality, or worse, the luxury of a sanctimonious middle-class, e.g. The Wire. Breaking Bad manages to depict the often very sympathetic conditions of/for criminal behavior, without in any way exonerating said behavior. Instead, it uses its ingenious premise to explore a variety of existential questions, even deigning to – gasp – offer some answers. And not the kind you would expect.

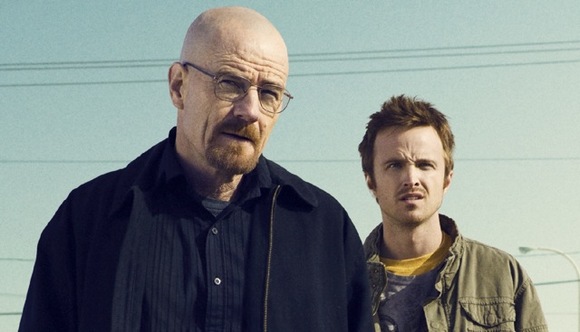

In Breaking Bad, trespass reaps more than suffering – it reaps punishment, in the form of alienation, deceit, death, and more tresspass. The slopes of self-justification are very slippery indeed. Major props should be (and have been) given to Bryan Cranston for playing Walter White so brilliantly and with so much subtlety and dimension. He resists vilification and adulation in equal measure. We root for him because we understand him. The same goes for Walter’s sidekick/surrogate son Jesse Pinkman. But just because we can sympathize with these characters doesn’t make their actions any less heinous. That is, the human condition may be something we all share, and it may be something that’s out of our control (like terminal cancer) but that’s not enough to excuse it. Someone’s not only gotta pay, someone is going to…

In anticipation of the season 4 premiere, The NY Times magazine profiled the visionary behind the show this past week, Vince Gilligan, and boy what a profile! Clearly he’s not reading much Rob Bell:

What sets the show apart from its small-screen peers is a subtle metaphysical layer all its own. As Walter inches toward damnation, Gilligan and his writers have posed some large questions about good and evil, questions with implications for every kind of malefactor you can imagine, from Ponzi schemers to terrorists. Questions like: Do we live in a world where terrible people go unpunished for their misdeeds? Or do the wicked ultimately suffer for their sins? Gilligan has the nerve to provide his own hopeful answer. “Breaking Bad” takes place in a universe where nobody gets away with anything and karma is the great uncredited player in the cast. This moral dimension might explain why “Breaking Bad” has yet to achieve pop cultural breakthrough status, at least on the scale of other cable hits set in decidedly amoral universes, like “True Blood” or “Mad Men,” AMC’s far-more-buzzed-about series that takes place in an ad agency in the ’60s.

“If there’s a larger lesson to ‘Breaking Bad,’ it’s that actions have consequences,” Gilligan said during lunch one day in his trailer. “If religion is a reaction of man, and nothing more, it seems to me that it represents a human desire for wrongdoers to be punished.

“I feel some sort of need for biblical atonement, or justice, or something,” he said between chews. “I like to believe there is some comeuppance, that karma kicks in at some point, even if it takes years or decades to happen,” he went on. “My girlfriend says this great thing that’s become my philosophy as well. ‘I want to believe there’s a heaven. But I can’t not believe there’s a hell.’ ”

…[Gilligan] wanted a leading man who would not only change over the course of the series but also suffer crushing reversals with lasting impact.

That is something new. The depravities of leading men in TV dramas traditionally don’t leave permanent scars. Don Draper of “Mad Men” is still pretty much the tippling rake he has been from the start, despite a flirtation or two with confession and reform. Tony Soprano tried, through therapy, to improve as a human being, but he didn’t get very far. Dr. House of “House” will always be a brilliant cuss. Walter White progresses from unassuming savant to opportunistic gangster — and as he does so, the show dares you to excuse him, or find a moral line that you deem a point of no return.

…consider the “simple chaos” take on the universe as represented in movies by Woody Allen, a director whom Gilligan admires. “And Woody Allen may be right,” Gilligan says. “I’m pretty much agnostic at this point in my life. But I find atheism just as hard to get my head around as I find fundamental Christianity. Because if there is no such thing as cosmic justice, what is the point of being good? That’s the one thing that no one has ever explained to me. Why shouldn’t I go rob a bank, especially if I’m smart enough to get away with it? What’s stopping me?”

Word of warning: The show really is gruesome in places. It’s also pretty slow-paced. You sort of have to get through the first season. It hit its stride, though, in season two when the show somehow integrated both its addiction undercurrent and its inimitable sense of humor with all the double-life thriller/Southwest outlaw elements. Season Three ranks as one of the most complete and successful artistic statements ever to grace the medium, and Season Four is not far behind.

COMMENTS

11 responses to “Living Hell and the Moral Vision Behind Breaking Bad”

Leave a Reply

I think that “Breaking Bad” is sheer genius and without a doubt, the best show on television (I bailed on FNL when they started on the Tyra/Landry murder subplot).

Walter’s descent is horrifying and there seems to be no hope for him, but it is Jesse who breaks my heart. His is the only hope of any redemption, if redemption there be in the BB universe.

Honeybee-

I definitely don’t fault you for giving up on that particular plotline from season 2. Most of us FNL diehards don’t even consider season 2 part of the canon. The show was under a huge amount of pressure from the network to increase ratings by introducing salacious plotlines. Rest assured, they righted the ship in season 3, thanks in part to the writer’s strike. So i normally tell people to just skip season 2 altogether. Seasons 3-5 are utter genius and deserve a second look.

as for jesse’s redemption, we’ve definitely seen little hints of it here and there, and while i too am holding out hope, i can’t see things ending well for either Walt or Jesse. But who knows?!

Considering the excellent taste and fine discrimination of Mockingbird, I will certainly take you suggestion and pick up FNL again after Season 2.

But, David, please say it ain’t so that you think “The Wire” was sanctimoniously middle class!! (It’s in my pantheon of television greatness, along with BB, Deadwood and The Sopranos — with Sons of Anarchy sneaking in as a guilty pleasure)

Heavens no! I loved The Wire. In fact, one of the very first posts I put on Mockingbird dealt with it:

https://mbird.mystagingwebsite.com/2008/03/wire/

I suppose that looking back i see a slightly patronizing view toward folks that took moral concerns seriously, that certain forms of morality are luxuries that the impoverished can’t afford. Which may or may not be true, but it’s certainly depressing. To see good and bad as inconsequential or irrelevant, that is. But maybe I’m off base? (Marlo might not concur).

Like Honeybee, I’ll check out this show based on your past perspectives.

But the idea that “certain forms of morality are luxuries the impoverished can’t afford . . . may or may not be true” goes completely counter to the gospel. I would rank it with those compassionate sounding lies of the enemy. The Wire bought into that lie, and sold it to viewers. And much of our current prison overpopulation can be attributed to this pity-based idea that being “bad” isn’t as big a deal when somebody’s poor. We can excuse it. This is terrible theology, and it’s infected huge swaths of art-based-on-crime (mystery and suspense books, tv crime dramas, modern crime flicks). I say this as someone who writes mysteries for a living.

Generally speaking, and with grateful apologies to Zaccheus et al, it was the poor who embraced Jesus first, not the rich. And their worship was often seen by God as more pleasing: the poor widow’s contribution to the temple coffers, the destitute pouring out expensive oil on Jesus. And, for heaven’s sake (literally), Jesus was poor.

One danger of this idea — that bad choices in poverty are “more excusable” — is that it only encourages more of the same. (Actions and ideas). But the bigger problem is that it dilutes the power of grace. If sin can be attributed to circumstances, who needs mercy and forgiveness?