1. First up, the boys are not alright. Nowhere near so. Neither are the men. They’re struggling and suffering and despairing and overdosing in unprecedented numbers, especially in comparison with their female counterparts. This familiar (and easily co-opted) refrain has received what sounds like a wide-ranging and compelling treatment in Richard Reeves’ new book, Of Boys and Men, released this week. I suspect Reeves’ book inspired Ruth Graham’s heartening profile of F3 in the New York Times last week. (“It reminded me of how urban women used to talk with me about SoulCycle, only these guys were suburban fathers.”)

I’ve gone on record about the importance of that group in my own life, so I was chuffed to see it featured so sympathetically in a publication that could’ve easily thumbed its nose. Anyways, in his newsletter this week David French used Graham’s column and Reeves book as a jumping off point for some further reflection on how the politicization of masculinity is making the crisis worse. He writes:

While left and right fight furiously over who’s to blame for the fact that young men are falling behind in school, men are overwhelmingly more likely to die of despair, and men are suffering a crisis of loneliness and friendlessness, we’re neglecting the most mundane and powerful of explanations—the world changed, and men have been struggling to adapt ever since. […]

In his outstanding new book Of Boys and Men, Brookings Institute senior fellow Richard Reeves documents these immense social and economic changes more effectively than anyone I’ve read, and he does something else truly important — he argues that our ideological wars over masculinity are making everything worse.

Almost half of all men report having three close friends or fewer. Between 1990 and 2021, the percentage of men who reported have no close friends quintupled, from three percent to 15 percent. The percentage who reported ten or more close friends shrank from 40 percent to 15 percent.

If left and right are leading us astray — and if the world has changed irrevocably — what can we do to provide men and boys with a sense of virtuous purpose? I think we find the answer in the arenas where men struggle the most — as husbands, fathers, and friends […]

Not everyone can or should get married or have children, of course, but virtually everyone can form friendships. Telling men that true masculinity is found in heroism or adventure or physical strength, by contrast, can lead to a profound sense of loss or emptiness when real life turns out to be far more mundane, and it can trivialize and minimize the immense purpose and value of diligent work and steadfast love.

Perhaps it should come as no surprise, then, that friendship often serves as a euphemism for grace. I tried to say as much in Low Anthropology, in the section directly after the one about F3 believe it or not (p. 142-3). That is, a friend is a person you spend time with because you want to, not because you have to or need to. You confide in your friend because you are assured of their charity toward you. They both like you and love you — which means they’re familiar with your less-flattering qualities. They have witnessed you putting your foot in your mouth and have stuck around. In its purest form, friendship is the term we use to describe a non-performative relationship. Burpees notwithstanding.

A low anthropology allows for friendships to blossom because it allows for the whole truth. It does not expect people to be better or different than they are. The template for this sort of community is Alcoholics Anonymous and its many offshoots, where members open each meeting with a confession of “Hi, I’m _____, and I’m an addict.” Alcoholics Anonymous is a community bound together by shared weakness and is therefore a real community — a transformative one. Good churches sometimes function similarly.

2. Yet the above is also why our place of employment will never ameliorate our core loneliness. The employee doesn’t tell the boss why they were out so late last night, and the boss doesn’t confide in the employee their anxieties about the company’s future. There’s a wall of propriety but also a wall of contingency between them, as there is in every conditional relationship. You could lose your job. A certain amount of loneliness — or independence — is baked into the equation.

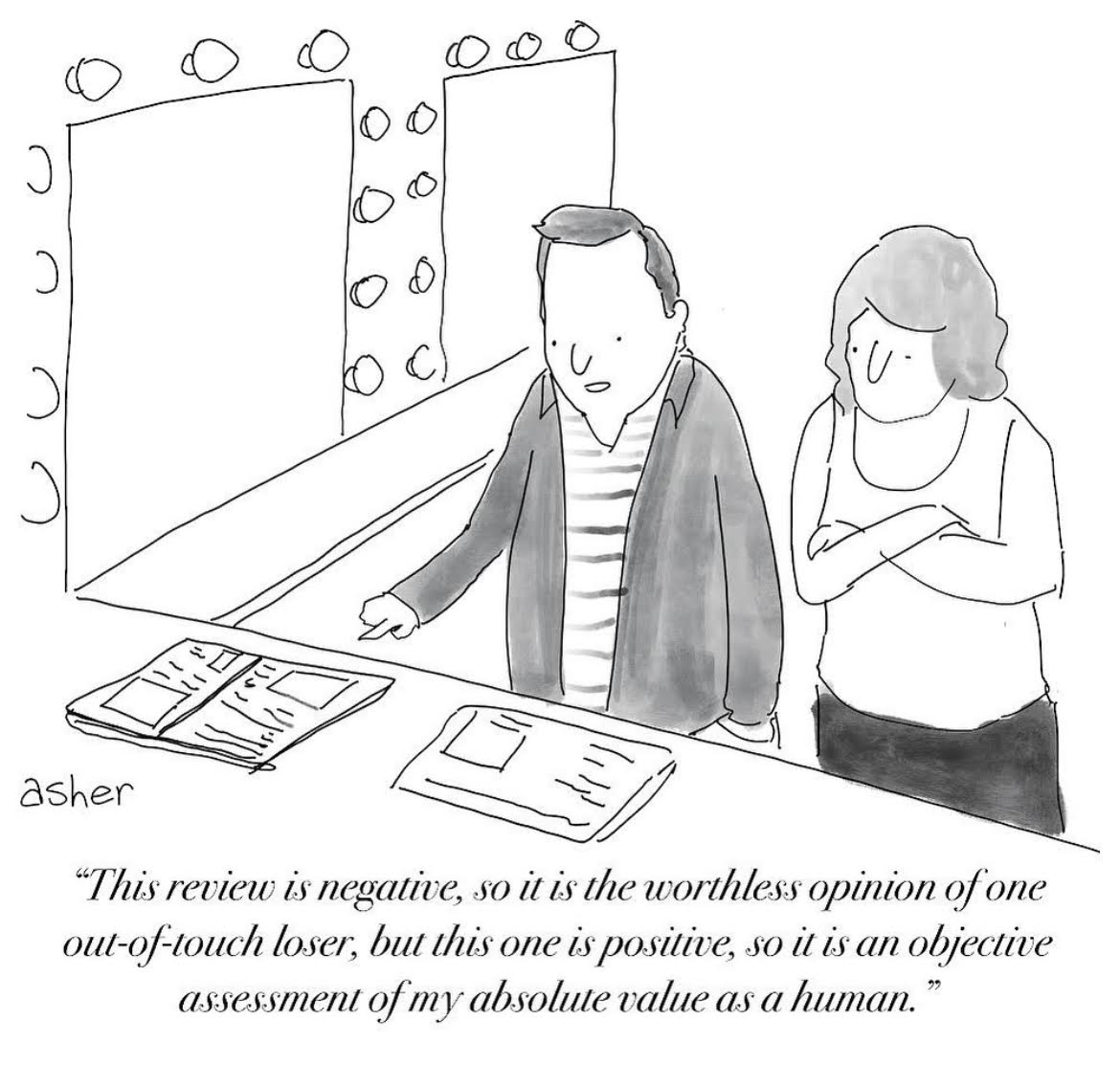

Asher Perlman channeling pgs 96-98 of Low Anthropology

Pamela Paul got at this very dynamic in her latest NY Times column, “Do Not Bring Your ‘Whole Self’ to Work.” Work life is not the same thing as home life, no matter how much we may wish or pretend otherwise. Keeping the two separate, she contends, not only allows for a certain degree of professionalism in the workplace, it also ensures some limits on what work can expect of its employees — and vice versa #seculosity:

According to TED talker and corporate consultant Mike Robbins … it’s “essential” to create a work environment “where people feel safe enough to bring all of who they are to work.” Bringing the whole self is a certified buzzphrase at Google and encouraged at Experian. In this new workplace, you don’t have to keep your head down and do your job. Instead, you “bring your whole self to work” — personality flaws, vulnerabilities, idiosyncratic mantras and all.

[…] for the world outside the H.R. department, the phrase “bringing your whole self to work” is almost guaranteed to induce a vomit emoji. Rarely has a phrase of corporate jargon raised so much ire and rolled as many eyeballs with everyone I’ve talked to about the subject.

After all, the office isn’t the only place you exist — why should they get to have all of you? […]

Nor is it fair to ask the workplace to deal with all your hopes, dreams and problems. “A lot of staff that work for me, they expect the organization to be all the things: a movement, OK, get out the vote, OK, healing, OK, take care of you when you’re sick, OK. It’s all the things,” an executive director for an advocacy organization recently told The Intercept. “Can you get your love and healing at home, please?”

3. Next up, Christianity Today published a lengthy piece on Dallas Willard’s fears about the spiritual formation movement, written by his teaching assistant James Bryan Smith. I’ve always been fairly skeptical of the disciplines from a grace-standpoint, having seen them wielded too often as an outside-in habit-formation mode that feels like thinly-veiled Christianized self-help. That skepticism has softened somewhat over the years, however, as I’ve witnessed the anti-discipline ‘gospel-centric’ stance prove no less prone to idolatry or gracelessness. Whatever you make of the movement, it’s fascinating to read about Willard’s own reservations about means and ends:

[Dallas] worried that the focus would be on the practice of the spiritual disciplines themselves rather than on what they were intended to do. Dallas felt this would naturally degenerate into a focus on technique — on the how and not the why of the spiritual exercises […]

Nearly every week I receive a copy of a new book on Christian formation, and almost all of them are about a particular practice, such as slowing down, solitude, fasting from technology, using the Enneagram, gratitude journaling, or creating a rule of life. They give great attention to the how of a certain method while championing its apparent benefits, but they often neglect to help readers truly understand or cultivate the deeper why […]

Becky Willard Heatley spoke with me about her father’s concern that the disciplines would be “elevated and separated” from the rest of transformation. “He believed this would be dangerous,” she said, because the disciplines then become a form of idolatry — the means become the ends. We become more focused on the disciplines than we are on God, breaking the grip of sin, or the care of our embodied souls.

Many of us have allowed the spiritual disciplines to become a form of idolatry, divorced from historical, biblical, theological, and anthropological understanding. Many of us have inadvertently assumed these practices will transform us. But the practices themselves are powerless without God.

4. Nostalgia for bygone status markers is nothing new, especially for those of us who once frequented indie record stores. But I suppose it’s a mistake to claim that the “coolhunt” is somehow over — or even diminished. Writing for the Atlantic this week, Amanda Mull proposed that the restaurant world has more than filled the vacuum of urban status-seeking that the Internet reconfigured for us. “Nothing is Cooler Than Eating Out” she claims, tossing in a few #seculosity-friendly observations into the mix as well. It would appear that capital-T Taste (both literal and aesthetic) plus scarcity plus social media plus embodiment equals Justification-by-Reservation:

When anything is both culturally meaningful and scarce, it generates a hunger of a different sort … As the journalist Helen Rosner wrote in The New Yorker last year: “At impossible-reservation restaurants, the food is always ancillary to the potent validation of simply being allowed past the door.” […]

“In the 20th century, almost everything — all of our lifestyle choices — had the ability to become status symbols because the barriers for information and access were still very high for a lot of things,” W. David Marx, the author of Status and Culture: How Our Desire for Social Rank Creates Taste, Identity, Art, Fashion, and Constant Change, told me. But when you don’t have to know a guy who knows a guy to get the indie records that your local store doesn’t carry, or live in a major city to develop an appreciation for French New Wave, or have fabulous wealth to wear new outfits all the time, those actions don’t hold the same symbolic meaning they once did.

That hasn’t killed coolness, though, even if, as Marx told me, that’s exactly what early tech optimists hoped the internet would do. That’s where restaurants come in. You can digitize access to reservations, but the proper dine-in experience itself must be had in the physical realm, and that inherent resistance to digitization has made them even more salient status symbols to an even larger group of people, Marx said.

The reservation frenzy has become so ridiculous, at least in part, because of all the other kinds of in-person social experiences that people no longer have. Americans go out for movies less frequently than they did a decade or two ago, and attendance at religious services and membership in civic organizations are both flagging.

5. In Humor, I chuckled at Reductress’s report, “Mattel Introduces New Barbie Whose Whole Thing Is Setting Boundaries.” But McSweeney’s “An Open Letter to Bluey’s Parents: Please Stop” by Kate Allen Fox plumbed more sympathetic territory:

Because, Mum and Dad (do you prefer Bandit and Chilli? We are all adults here), you’ve made opting out not an option. You’re never too busy to play. Never say no to an increasingly ridiculous game. In your seven-minute bursts of animated Masterpiece Theater, you’re almost always ever-patient, entirely present parents.

That works fine when your children are scripted into being semi-reasonable creatures. Call me when you’ve lived with a drunk-on-power toddler for nearly three pandemic years (roughly 2.7 billion cartoon-dog years).

6. Gut-Punch Social Science Study of the Week comes to us via the Conversation: Researchers found significant declines in extroversion, openness, agreeableness and conscientiousness in 2021/2022 compared with before the COVID pandemic. These changes were akin to a decade of normal variation. Oy vey. I dare say we’ll be uncovering other aspects of the fallout for years to come.

7. Saddened to hear of the death this week of Brother Andrew AKA Anne van der Bijl, AKA God’s Smuggler. I have a copy of the God’s Smuggler comic book displayed in my office, believe it or not. Christianity Today published a moving roundup of tributes from Arab Christians worth reflecting on:

In 1992, when 415 militants from Hamas were expelled by Israel to the side of a mountain in southern Lebanon’s Marj al-Zohour, Brother Andrew saw an opportunity to practice Matthew 25. He delivered tents, food, and medicine. “There are no terrorists — only people who need Jesus,” he later wrote in Light Force. “As long as we see any person — Muslim, Communist, terrorist — as an enemy, then the love of God cannot flow through us to reach him.”

“Andrew was always on the hunt for new rebels and radicals willing to go to the darkest places on earth, at the risk of death, to change the world,” wrote David Curry, CEO of Open Doors USA, in tribute this week. “And he was grateful for everyone who joined his cause.”

Sara is one such man. Brother Andrew regularly visited his church in Jerusalem, both when Sara was a young believer in 1992 and later when he led the same congregation. But in between, when the Open Doors founder heard from the pastor that the poor believers had pledged to send Sara to the Philippines for seminary education, he pulled out all the money he had in his pocket — which exactly matched the funding gap.

8. I’ll close with a beautiful long-read in the Guardian about two young Englishmen, Jack Chisnall and Josh Dolphin, who formed a standup double act as students only to both pursue ordination in the Church of England after graduation. Needless to say, this came as a shock to their peers, one of whom, Lamorna Ash, decided to profile their unexpected journey(s) for the publication. The lengthy piece doubles as an account of conversion more broadly (in a post-Christian setting), as well as an introduction to the eccentric, otherworldly charms of Anglo-Catholicism:

When [Josh] returned to Oxford [after a panic-attack-induced year off], Josh sought out ways to stave off another breakdown. He ended up attending morning prayers with a friend at his college chapel. It was not a conversion, but it provided a stabilising ritual, which seemed to open a new region in his mind — this could be somewhere you go when you’re in trouble.

Jack had a similar crisis of confidence in his final term. One evening he walked over to his tutor’s office and asked him: “What’s the point in literary criticism?” From there, it was a small step to “What’s literature for?” The questions kept unfolding all the way up to “What’s the universe for?” He sees this moment as the origin of his faith. His younger brother, Callum, considers it inevitable that Jack ended up at God. He had that kind of mind. “It was too big a question for him not to get his teeth into,” he said.

When I suggested to Rev Helen Fraser, the Church of England’s head of vocations, that many of the conversions I’d heard of were borne out of despair, I found myself immediately apologising. I imagined she might think I was undermining her faith — equating it with mindfulness, therapy, functional tools to cope with being alive. “It doesn’t sound negative to say you find God when you’re low,” she corrected me. “I would just say instead: ‘God finds you when you’re low.’” I had begun to understand that this reframing is part of what it means to be Christian: fate elided with faith, each experience reworked into further evidence for the existence of a loving God.

Strays:

- The editors of Christian Century, following on from the outpouring of grief in the UK after Queen’s death, echoed something Sarah Condon has mentioned on the Mockingcast “We need ritual for our collective grief.”

- Speaking of the Mockingcast, we put out a new episode this week, “Church of the Holy Dysfunction.”

- In preparation for the release of the Sleep Issue of The Mockingbird magazine, stay tuned for a big announcement next week about a special fire-sale!

- Low Anthropology Update: I had the immense privilege of doing interviews with beloved grace gurus on differing sides of the so-called spectrum this past week. Nadia Bolz-Weber hosted me on Instagram for a live Author Chat and then Steve Brown had me on his titular radio show to talk about the book. So much fun. Video of the latter below!

- Incredibly touched (and moved) by this review of the book by Jonas Ellison on Substack. Video review — yowza. THANK YOU Jonas! His newsletter is phenomenal, btw, and highly recommended.

- DC — and NYC — metro area friends, I’ll be in your neck of the woods this week for the Low Anthropology Tour! On Wednesday evening, 10/5, I’m speaking at All Saints Episcopal Church in DC (on Chevy Chase Circle) at 7pm and then on Thursday at 7pm I’ll be at the Chapel at St George’s Episcopal near Union Square in New York City. Come one one, come all!

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply