In honor of our upcoming merger with Buzzfeed (just kidding), there are a few very commonly used, but imprecisely defined, Christian words which could stand some rethinking in how we use them.

Redemption – Often you hear questions like, “Can ____ be redeemed?” or ask questions like, “How will God redeem that job, that relationship, that bad decision? Will God redeem the suffering caused by Kim Jong-Un?” Or, at one dinner, “Can competition be redeemed?” The word means something like paying a price to buy back someone who is a slave or indebted, clearing their debt from one’s own store. A beautiful way to describe Christ’s work on behalf of his people, but it doesn’t really make sense to apply it to experiences, memories, situations, or abstract entities. Such sentiments as those above may act parasitically on the original word, channeling its force into vague, emotionally-saturated questions which say more about ourselves than God. Because what we’re really asking is for power to peer into Providence’s muddled ways, to make our tangled lives seem lucid and linear. Of course, God does work for good in all things, and God does redeem us through Christ. In the Bible, people are always the ones redeemed – “Israel”, “his people”, “our bodies”, “us” – and the word does not apply to events or situations. Stretching the word too far beyond this biblical warrant starts to sound like “Can forks win?” – an exciting question which could be debated for years, mainly because there’s so little precision and meaning in its framing.

Free Will – The phrase is usually thought of as meaning “the ability to do whatever one wants to do and physically could”. Freedom, we tend to assume, is directly correlated with our field of possibilities. This definition is very much conditioned by contemporary America, where potential, which we fetishize, requires freedom to actualize itself. And our focus upon individual self-actualization contributes, too; whatever I feel is my desire or destiny, I want to be able to go out and do it. This is problematic in religion, because a concept so deeply tinged by social circumstances cannot function well as a touchstone of theological debate, but often is.

Instead of freedom as meaning the ability to do whatever one might want to do, the understanding of many theologians in the past has been freedom as the ability to do that which one does want to do. The distinction is subtle, but important. If you have a child, chances are you don’t choose to love her; you love her by necessity. You never had a choice, but you still love her freely. Thus for Augustine, God causes our will to desire the good; God acts upon our will in such a way that we freely desire it. We do not stand above our lives like some impartial chooser, but in the most important matters, our desires freely inform our emotions and choices. Again, we love our children freely not because we theoretically could have chosen not to, but because we are doing that which we desire to do. The emphasis of this element in free will by no means solves such debates as Reformed versus Arminians (even Molina and Bañez couldn’t agree), but it could certainly lessen the tension, add precision, and save some ink. Certainly the most complex topic on the list, I’d recommend Augustine’s “On Free Choice of Will” and “On Grace and Free Will”.

Supersessionism – A word which means vaguely that the new, Christian covenant “supersedes” the Jewish one, and it has a negative connotation. Beyond that, definitions are hopelessly muddled. They range from “the belief that Jews cannot be saved” – which makes it an awful and misguided term – to “the belief that the new covenant fulfills the Jewish one” – which makes the label an indisputably Christian one. Many people with firm definitions are agenda-driven. The fact that there are degrees of supersessionism is obscured by definitions, and the term can’t be properly defined without taking account of these degrees and explaining what each covenant means within this context. It doesn’t help that ‘covenant’ too is a tricky term, and supersessionism has come to function more as a convenient term of denouncement than a meaningful descriptor.

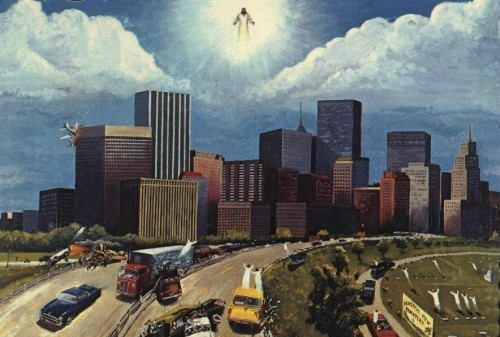

The Rapture – In its Left Behind form, the concept was invented by layman John Darby after eighteen centuries of a comfortably non-dispensationalist Christianity. Persuaded by Darby, Cyrus Scofield argued for his ideas in the liner notes of his bestselling reference Bible, and the notes were, to many Americans, presumed to be authoritative because they appeared between the covers of the Bible. Since then, the idea has garnered little theological support. Despite its shrill tone and political agendas, Barbara Rossing’s Rapture Exposed works as a nice deconstruction of the idea.

Repentance – From the Greek metanoia, roughly “afterthought”, repentance refers primarily to the examination of one’s conscience to remember wrong thoughts, actions, words, or feelings, and perhaps also to examine the contributing motives and/or character defects leading to such sins. Or, more passively, it could be simply removing distractions and allowing our normally-suppressed consciences to speak. Defining the word properly is crucial, insofar as it is universally regarded as a central part of Christian life. In the current American Protestant world, and notoriously during periods of Catholic history, the concept has been confused with expiation (donate X florins and your sins will be removed) or the resolve to live a better life. The latter is found as a result and companion of true repentance, but, as life-improvement flatters our pride and sense of control more than does remembrance of past wrongs, often we falsely make the resolve to live a better life into the keystone, or even exclusive meaning, of repentance.

Union with Christ / Participation in Christ – Phrases increasingly popular among American Protestants, it generally should be remembered that these concepts make sense only in Catholic, Anglo-Catholic, and Orthodox circles. For perhaps the best use of these concepts in Protestantism, check out the work of Finnish Lutherans like Tuomo Mannermaa, but even this might be a stretch. Some Reformed folks are trying on these ideas now, but squaring them with Calvin is pretty awkward. Again – a common theme – their appeal in Evangelicalism comes from an abstract, emotionally fertile use of the words, though not a precise one.

Relationship with God – More on this in our upcoming magazine issue, but lots of problems. First, it’s never used in the Bible; second, it implies an unfortunate comparison with human ‘relationships’; third, it seems to imply something which is in flux, and thus something which can improve or deteriorate; and fourth, it obscures the fact that the way we relate to God is different from the way God relates to us. If ‘relationship’ were replaced with a more biblical emphasis on relational identities – e.g., God is like a father, God is the Giver of all good things, God is our shepherd, Christ is our Savior, we are God’s children, we are heirs, we are sheep, we are those saved – if such a substitution occurred, we would no longer have a ‘relationship’ to ‘build’, but we would have a set of accomplished facts to contemplate, internalize, get used to. With more verbal precision comes less conceptual room within which we may maneuver, but given the facts which have been revealed to us, that’s almost certainly Good News.

Picture a Republican and a Democrat arguing about which party best promotes ‘freedom’; as long as the word remains undefined, they could argue for days, and each would leave justified in his own mind, because each has defined the word selectively. It would also be a colossal waste of time. At one lecture I attended, students were thrilled to hear an academic affirming the idea of “participation in God”, because it sanctioned their idea of building the kingdom alongside God, collaborating in his work. Unfortunately, the academic was talking about a different, metaphysical idea – the Q & A was like ships passing in the night.

Theological talk is often infected with bias toward self-justification. More precisely-defined words can be a bulwark against such self-justifying isolationism, building a semantic cocoon within which all of one’s own opinions make sense, but one which nothing new can penetrate. Revisiting our words and considering the way others use and have used them, would save time and energy at the least, and may even wear down our walls a little.

(Featured and top images from tomgauld.com).

COMMENTS

11 responses to “Seven Common Theology Phrases That Should Be Used More Precisely”

Leave a Reply

Merger with Buzzfeed???

Sorry MC – was joking there

Well, if it were not for losing the non-profit status, that might be an odd but interesting coupling.

If we were going full-blown buzzfeed I think we need the Inigo Montoya gif “You Keep Using That Word, I Do Not Think It Means What You Think It Means” in this post somewhere.

Here’s a very easy to listen to class on “free will”:

http://theoldadam.files.wordpress.com/2014/07/pastors-class-22free-will22-etc.mp3

I think you’ll end up listening to it several times. It’s that good and explains it in simple terms.

Thanks.

Def in my top seven favorite Will McD posts of all time!

Awesome…..the “relationship with God” term here is so well defined/exposed. The misguided notion that a relationship with God can move along a continuum, or in a “state of flux”, is so pervasive in our Christian culture – what a great idea for the next Will McD book!

Will, you articulated very well something I have thought for some time now re: “relationship with God” or “my personal relationship with God”. I like the idea you present in this line: “if such a substitution wre to occur, we would have… accomplished facts to contemplate, internalize, get used to”. Our walk with God is not something to “build” or “cultivate”. B/c of the cross, it is an established objective fact – not a subjective experiential “thing” we develop as we do “x,y, and z” (i.e. read, pray, have quiet time, fellowship, make godly choices, etc). I really dislike the notion of “things we can do to grow our relationship with God” or “ways we can grow as Christians”. Christ Himself accomplished and secured our growth externally, outside of, and apart from us historically 2000 years ago. This is solid ground… real concrete stuff that has nothing to do with our considering the question one CCM singer posited years ago in a song, “how are things between us?”. Thanks for writing this piece – I almost never hear the Christian life presented this way. Good stuff! And also in my fave blog posts period!

Squaring phrases like “union with Christ” and “participation in Christ” with Calvin is pretty awkward? Have you read the Institutes? Union with Christ is a major theme for Calvin. Don’t believe it? Check out J. Todd Billings “Calvin, Participation, and the Gift: The Activity of Believers in Union with Christ.” Or any Calvin scholar, for that matter, who has written on Calvin and justification and/or sanctification.

Redemption and free will were handled well. Your explanation of repentance stems from the Greek idea, but what about the Hebrew? If we’re going to structure our ideas based on coherent definitions, it is important to consider when multiple terms (from multiple cultures) are used to denote said idea. (This site has some good info on the difference between metanoia and teshuva: http://www.hebrew4christians.com/Holidays/Fall_Holidays/Elul/Teshuvah/teshuvah.html )

The Union with/ Participation in Christ section only tells Protestants not to use it, rather than saying what it really means. I agree that one’s Relationship with God is set by what Christ accomplished but what vernacular would you suggest one use when refering to one’s “closeness” to God? Clearly there is a feeling of closeness one can have with God that can dissapate or strengthen, sometimes due to personal devotion and sometimes just seasons of life. All in all this is a good post but the problem with saying that one is using a term incorrectly, is that one has to suggest another term for use or incorrect dialogue will continue.

“Participation” in particular is a word without any meaning. Does it refer to baptism? Ethics? Ontological union? eucharist? The list goes on. Yet it’s *always* said without any clarification and everyone just nods in approval.