Mr. Miyagi has played it so cool the whole movie long that when we finally see him respond, after the All-Valley Karate Tournament, after Sensei Kreese from the rival Cobra Kai dojo breaks Johnny Lawrence’s trophy and strikes his own students, there’s a feeling the audience has — one that we’re supposed to have — that goes something like ohhh, he’s going to get it now! We’re about to see justice enacted, wrongs set right. It tingles in the belly, the anticipation. As viewers of the film The Karate Kid (1984) will remember, what we actually see is Kreese attack Miyagi, who, just in time, steps smoothly aside causing the Sensei to miss, punching out the windows of a nearby car and rendering the weapons of his hands useless. Finally, we think, oh let justice roll down like a mighty torrent! Like a great rushing of waters! Miyagi raises his hand for a classic karate chop, growling from his dan tien to summon the power that we know can break clean through sheets of solid ice — what might that hand do to a man’s face? — only to stop the flood at the last moment, like some angel disarming a would-be sacrificer on the mountain. Instead of Miyagi annihilating this opponent, he deals out a playful honk of the nose, in a gesture a bit like the Native American practice of counting coup: a nick that says “I could have taken you out and didn’t.”

I’m thinking about The Karate Kid first because I grew up in the 80s, so I’m sort of always thinking about The Karate Kid. Yesterday as I wrote this, my son Sebastian wanted to play wrestling, so I taught him the crane kick. As the saying should probably go, “You can take the kid out of the 80s, but you can’t take the 80s out of the kid.” But more than that, I’m thinking about this scene because I’ve just finished teaching a college course on Shakespeare.

I probably shouldn’t have assigned it. I’ve taught it before and it always goes the same way. But there is so much good in it, so much that’s worth getting and so many conversations worth having, that the Merchant of Venice wandered onto our syllabus again this year, though cautiously. At first, the play goes pretty well; as Shakespeare texts go, it’s one of the easier ones for students to understand. They like imagining quattrocento Venice. They like the fairytale subplot about Portia, whose husband will be chosen via a kind of shell game, and who delivers the lovely “quality of mercy is not strained” speech. They understand Antonio, the merchant who needs to borrow money to achieve his grand dreams and who opens the play with a relatable bit of melancholia:

I know not why I am so sad

It wearies me, you say it wearies you,

But how I caught it, found it, or came by it,

What stuff ’tis made of, whereof it is born

[I know not]

And they’re stirred by Shylock, the Jewish banker, who argues for the universal brotherhood of all people, a plea for sympathy across religious and racial lines that still shocks in its candor.

Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions; fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, healed by the same means, warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer as a Christian is?

But then we get to the trial scene, with its dramatic reversal, and they’re shocked beyond resuscitation. It’s over. No way this is allowable.

What happens is this: Shylock has had it in for a rival businessman to whom he’s lent money the whole play long, and when the latter defaults on the debt, Shylock is legally entitled, to collect “a pound of flesh” from him as payment. It’s a crazy deal, but one Antonio signed with all due gravity and presence of mind. Like many of us I suppose, he never thought he’d really have to pay it. Anyway, his own Judgment Day comes and Shylock comes at him like an avenging angel with a knife — will he collect the pound of flesh from his face? From his genitals? From his heart? His worst enemy is entirely at his mercy. Antonio can’t even cry for help because police or community interference at this point would be illegal, and Venice is a city built on (water, and) legal contracts.

But then, the fine print. Through clever legal exegesis, the knife is knocked from the hand — Shylock can have his flesh but not his blood. Since he can’t very well manage that, the original legal judgement is moot. Defeated, Shylock is about to sulk off, when someone points out that the whole court has just watched him try to kill a fellow citizen. He was really going to shed blood right there in front of everyone. Shouldn’t he be tried for attempted murder? Yes, his life is now forfeit to Antonio; the strong are weak and the weak the strong! The whole kingdom is upside down! Antonio, perhaps tired of this legal circus and knowing just what it’s like to be afraid, asks no legal recourse apart from Shylock’s conversion: “that he become a Christian.”

For my students, this is the cruelest cut. Indeed, for most modern readers, it is a forced conversion, inauthentic on Shylock’s part and an evil imposition on the part of the court. And if it were that, I would agree, but Shakespeareans have been split on this matter more or less since the play debuted and I count myself among those who take Shylock’s conversion as spontaneous and real. This is tricky to talk about in the shadow of anti-Semitism, especially in Europe, and especially in the recent century, but I think it’s worth talking about still. First, because this play and this character have done such a great deal to argue for the dignity of the Jewish people and for oppressed people generally, and second, because the scene we’re discussing can be read as mercy itself enacted. But it happens quietly, as most such things do.

Maybe let’s think of it this way: what Shylock loses — and voluntarily as we will see — is not his cultural identity, but his captivity to the Law. To “become a Christian” in this case is not to leave behind his people, his heritage, or his religious practices so much as it is to accept that the universe runs on Grace. The play is not meant to depict Christianity as better than Judaism, but to depict how one man came to see how blind he’d been, even though he “had eyes.” In order to see that, he needs to be stripped of all the illusions of safety and self-sufficiency that being rich had afforded him.

The difficulty with reading this conversion is that it’s invisible, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t there. Hearing the request at trial’s end, Shylock simply says, “I am content.” But in the space between the initial charge and that statement, three things have taken place. First, Antonio finally has Shylock exactly where he has himself been many times: in his debt. But rather than lord it over him, he shows mercy. At first this doesn’t make sense to Shylock, still seething in his rage at having been cheated of what is his by rights. As Sensei Kreese tells his students, “We do not train to be merciful here.”

Second, Antonio is now pretty wealthy, having just won the trial, and he immediately asks that the money be used to provide for Shylock’s daughter, who has just been disowned, thereby demonstrating radical charity. What kind of person is this? Shylock knows how hard up for money Antonio is because he’s been his creditor. And now that Antonio is rich he just gives it away? And not to help his own people, but to help the family of his attacker? What kind of freedom makes such a gesture possible? As Shylock processes these wonders, we should be seeing the chains fall off.

Thirdly, Shylock has just committed attempted murder, and has forfeited his own life thereby. He’s guilty, and, knowing a thing or two about the law, he knows he’s guilty. The trial judge suggests an immediate hanging but defers to Antonio, who could now plunge the knife into him right there in the courtroom with complete immunity. It’s what Shylock would have done; it’s what he tried to do just moments ago. But no. Another power is at work. There is a deeper magic than the Venetian legal code, deeper than our eye-for-an-eye instinct. Without a thought, his life is gifted back to him. The old Shylock was all but dead in his transgressions, completely powerless to save himself.

When he realizes this, when he accepts it, as if out-of-nowhere: second life. Finally, so far have his sins been driven away, that he is not asked to answer for his crimes at all: he’s given no prison sentence, no banishment. Instead, he is welcomed into fellowship, to baptism. When the judge queries, “What mercy can you render him?” Antonio suggests he make an outward sign of the invisible grace he’s just experienced.

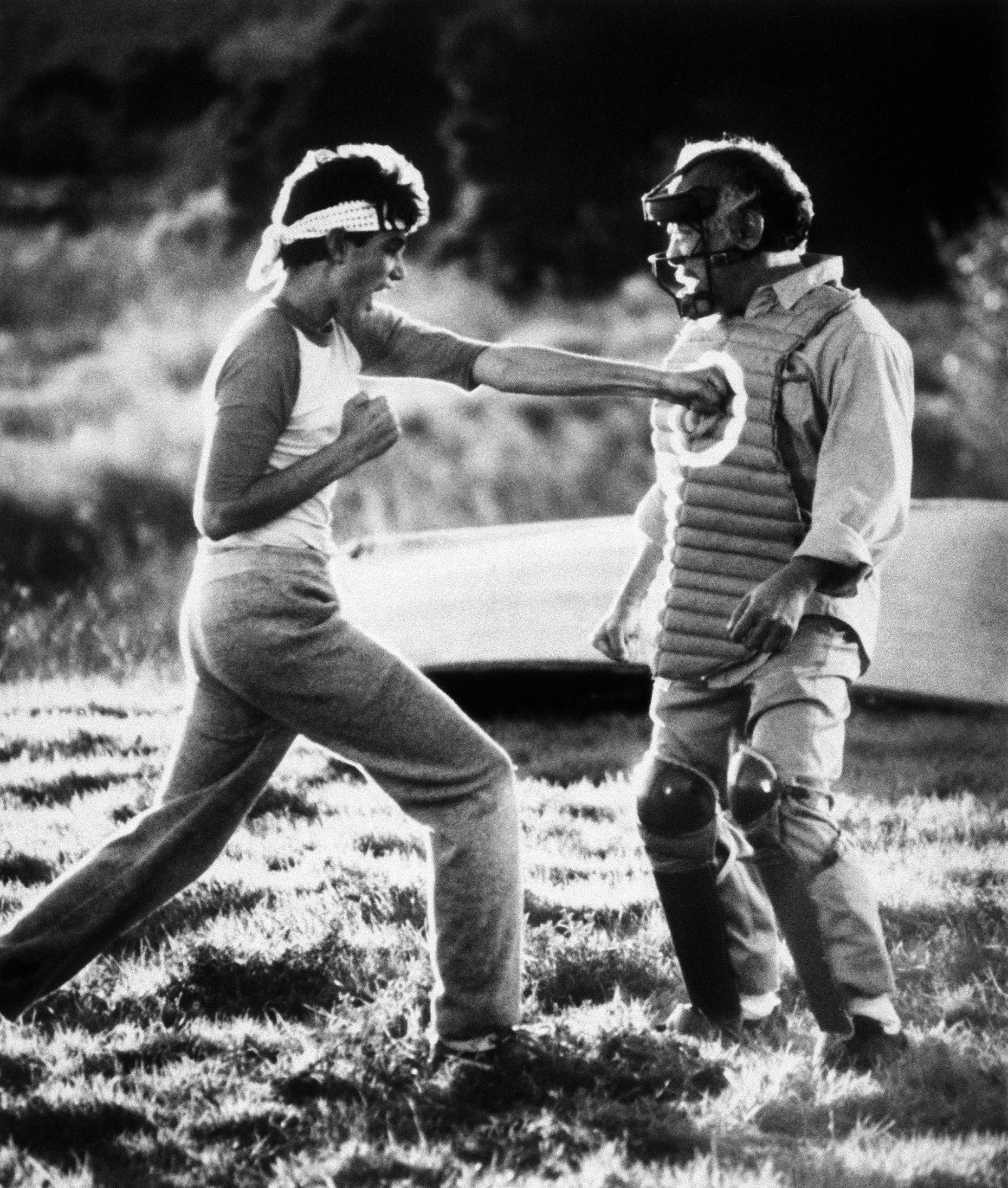

Daniel (Ralph Macchio) and Mr. Miyagi (Pat Morita) in The Karate Kid, dir. John G. Avildsen, 1984.

Walking back to the truck after the tournament, Daniel asks, “You could have killed him back there, couldn’t you?”

“Aye.”

“Why didn’t you, then?”

“Because, Daniel-san, a person with no forgiveness in heart lives in even worse punishment than death.”

In the play, Shylock is not forced to do anything; he’s freed. He’s just watched the old system crumble before the eyes that we know from the speech he has, and has seen the mercy that makes Christianity compelling. In short, when he says, “I am content,” we should believe him. And we should note too that his next comment — Shylock’s last in the play — begins with “I pray,” and goes on to describe how he isn’t feeling well. Even if he is only doing a typical bit of Shakespearean beseeching here, that’s still something. He’s needing. And it’s easy to read this particular prayer as defeatist, but it’s just as possible to read it as humanizing. The tireless persecutor is tired, the symbol of insatiability is now a mortal man, feeling things.

One more point that’s worth considering. The “hath not a Jew eyes?” monologue is rightly read as a plea for empathy, for understanding, for humanizing the other. But that’s only half of it. We’re not only supposed to see some of “them” as one of “us,” but to see ourselves in them. We’re not that different. When we read the play then, we’re not supposed to think of Shylock as some villain who gets his comeuppance, bloody fists waving around helplessly in the parking lot. Rather, we’re supposed to see that we’re him, too. We’re the ones who expect the law will save us. We’re the ones expecting our enemies to get what’s coming. We’re the ones who demand rewards for having kept the rules. And we’re the ones who need to lose all of those expectations, all our security, everything that we think makes us us if we’re going to find, well, what?

“Contentment” is a funny word. Technically, it means “to be satisfied with what one has,” but what Shylock has here in the end is nothing. Finally, he’s stripped of the wealth he’d been choking on (and that he’d choked others with); mercifully, he’s lost the social prestige attendant on a man with heirs and position; blessedly, he’s given up even the rage, the bitterness that had fueled both his business transactions and his relationships so far. He’s empty for the first time and content, one suspects, for the first time too. He loses the whole world, we might say. Helpless as a child, he’s finally in a position to receive something, which is everything.