I deal with a great deal of rejection. Hospice chaplains serve in a vital role but for patients my involvement is always optional. Spiritual support is always an “at will” service. As a daily part of my job I call and “offer” spiritual support. Some welcome the support. Others share that they have their own clergy. A few prefer to face end of life challenges with the support of their family rather than bearing their feelings to a total stranger. An even smaller group claim to be outright atheist, agnostic, or irreligious and have no problem making their refusal of me abundantly and at times theatrically clear.

By far, the biggest reason that people decline to see me is that they are just not ready. Even for highly religious people, having a chaplain visit symbolizes a certain uncomfortable finality. Sort of like the grim reaper, but in a clergy collar.

I don’t hear no very much. What I do hear a great deal of is not yet. “She’s doing so well today” they’ll say. Or “Oh, we’ll need to get the family together for all that.” Maybe they’ll share concern that “a priest coming out will really scare him. We haven’t told him that he’s dying.” We haven’t really thought about death. Things are just too chaotic for a minister to come to our house. Not yet. When I share my job title with them, images are conjured of last rites, deathbed confessions, final blessings, light music, or a gentle wind rustling through the curtains. They don’t visualize my job as the supportive presence companioning people through difficult times that I aspire to be. Instead, they react to the image of clergy-person they carry in their minds from movies and media. No matter how many lines I want in the script, they want somebody from central casting to enhance the scene by saying a few words — maybe with my back to the camera, or somberly chanting the 23rd Psalm off-screen. Not yet: your scene comes later. While I want to help people when they are dying, so many people treat me as if my job is only to manage death.

Very often, the calls I make to new patients and their families can feel like the cold calls I used to do while working for random companies during vacations from college. Half of the time I’m sure I rank in their minds and priorities slightly above the computer dialers that call them from unlisted numbers about their car warranties. I’m thankful at least that screaming and hanging up are not regular responses now. But the anxiety and apprehension of needing to make a “sale” persists. More than one nurse or social worker has laughed at me when I’ve used sales lingo like, “presume the yes” or “box ‘em in” to help them encourage patients to see me. But I can’t help it. In order to actually care for people, I have to convince and persuade them first. It’s a smaller scale of the work that all religious institutions have to do: reach people and keep them engaged.

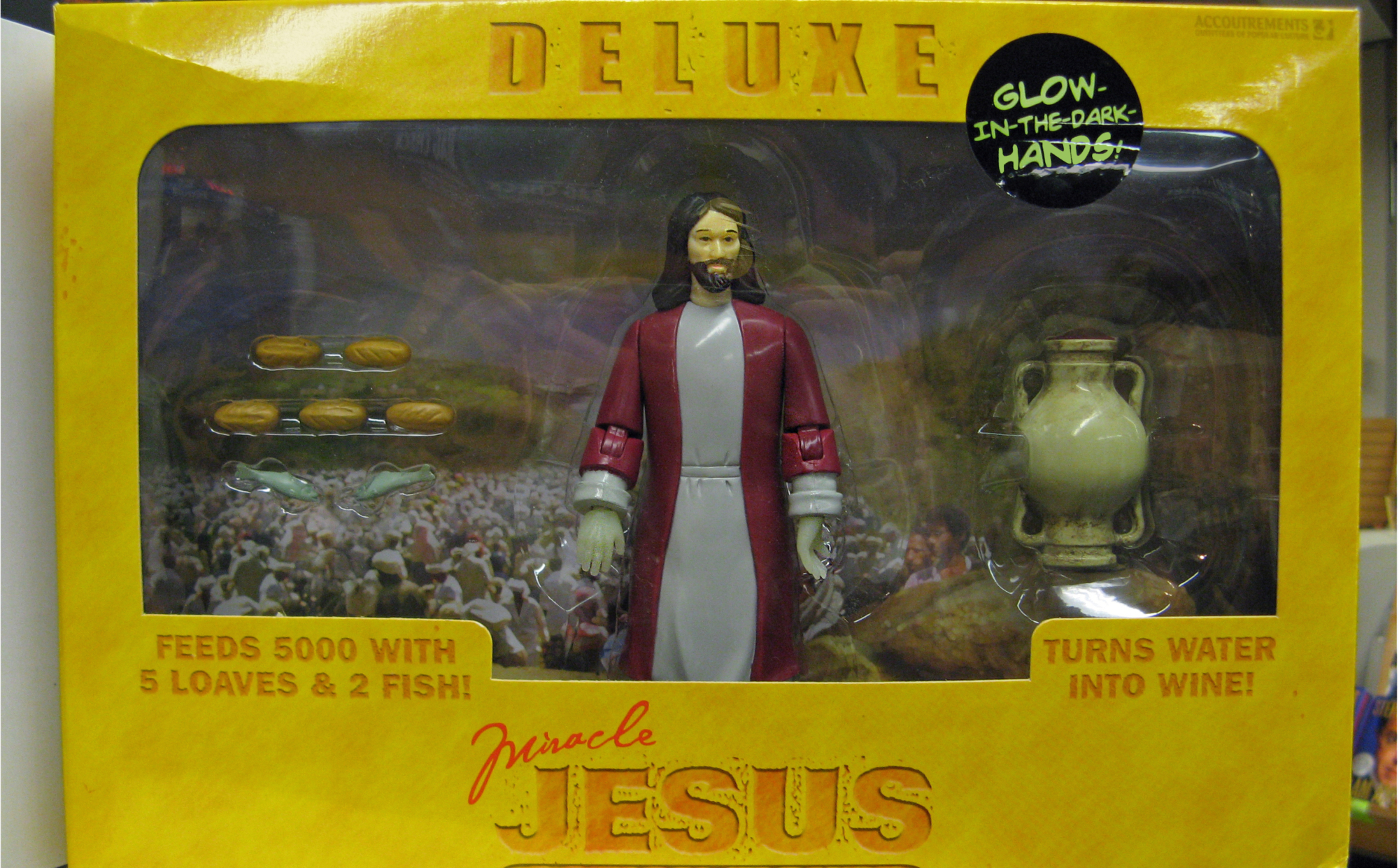

Religion and spirituality in America make more sense when you understand them as consumer goods: the designer church packed with programs targeted to different demographic groups, the “spiritual concierge” services connected with new luxury apartments, corporate mission statements that wax like doxologies and vision-quests, or the countless products that are sold not only by virtue of their merits but on promises of life transformation. All these point to a psychological truth. Americans are more likely to consume rather than practice their religion. This is a matter of comfort. Religion and spirituality are safer when they wait for you in the same spaces where you organize your life, enhance your free time, confirm and assert your values, and make sure that the world reliably conforms to your choices. People will gravitate to all sorts of wild and incredible beliefs as long as they can travel at their own pace.

“Don’t preach to me” is a demand and a request I hear from patients. Don’t judge me. Don’t mess with my life. Don’t tell me how to think. No matter how great their fear of death is, nothing compared their fear of losing control. And while I remain fiercely dedicated to a hospice philosophy which respects and adheres to the dignity and autonomy of patients facing death, I can’t help lamenting the place which the culture shoves me into when I’m calling new patients every morning. I don’t want to be a “spiritual concierge.” I don’t want to just be on-call for when someone has a question about burial vs. cremation, or when some holy sounding words are needed to fill the difficult silence around the death bed. Because I serve a God who wants more too. This God taught me how to do my job in the first place.

My employer took the dangerous step of hiring me the same year that I graduated from seminary. Anyone who has ever known a seminarian is familiar what I’m talking about. You emerge from those years of lecture halls and “student pastor” congregational experiences 100% positive that every tool you need has been learned and digested. All the while people tell you at every turn that you — “yes you” — are uniquely gifted for the work you’ve been called to. Were it literally any other profession, we would say this was empty arrogance, cockiness run amok. But hospice work sucked this unfounded confidence right out of me (and for the better).

At the outset of my work, I was knocked off my high horse with one of my more difficult visits to date. He was a man in his early 50s who had been bed bound for years after suffering from a neurological disease. I was told that he had been near suicidal and had agreed to see a chaplain at the promptings of his mother, who remained a faithful Roman Catholic. She wanted him to have prayers as often as possible.

I did not understand my job. I thought I had to make him feel better. During visits I would inanely ask how he was doing — or worse, I would try to imagine it for him as his disease caused difficulties when he tried to communicate. Looking to fill the awkwardly silent space, I would thumb through the Bible to find the right verse or some nugget of wisdom from a philosopher or a poet. I still laugh at that younger, inexperienced me. The nerve to think that I could somehow fumble on something in my spare time that a man bed-bound for years hadn’t already thought of. He had nothing but time to think on his condition. No matter how good a “spiritual concierge” I tried to be, no matter how many sympathetic questions, words, prayers, or emotional support techniques I tried, this was just an awful situation. This was not something to fix. He rightly became annoyed with my attempts. Sometimes during my visits, he would use what little ability he had to flip his blanket over his face as a clue that it was enough.

I always procrastinated coming to see him. I would wait until the very end of the month. I would try less hard. It felt too much like failure. One day I came into the room and, upon seeing me, he grimaced and began to inch the blanket up towards his head. I started talking to assure him that I was just checking in quickly to make sure he was okay. But I couldn’t help noticing the awful smell in the room. It was coming from his roommate on the other side of the curtain.

A nurse, clad in a gown, mask, and goggles poked her head through the side of the curtain. “Sir,” she said in that nurse voice both respectful and commanding, “we are changing a bedpan in here. So you might want to step out until we are done.”

Whether it was bravado or the Holy Spirit, I don’t know. But my next sentence was, “It’s okay. I’m his chaplain. If he smells it I can too.” My patient craned his head above the blanket and made eye contact with me. “That really smells,” I said. “I hope they wait a bit before they feed you lunch.” I got a smile and a faint laugh. And eventually a small conversation. We both talked a little about the homes we had left in the Midwest. We shared our common love of science fiction. I found out that he missed being able to read, so I said I could read him some novels when I came back. Future visits were incredibly pleasant. I got to say a few prayers. The smiles became more common than the grimaces. I came to look forward to seeing him.

That’s how I learned to be a chaplain. My job is not to be a “spiritual concierge.” My bag of tricks is not to offer rituals, prayers, or techniques to help people live their best lives. Illness, death, and loss chew up and spit out all of our “solutions.” They demand instead our honesty, our vulnerability, and our ability to surrender our pretensions to be anything other than a fellow human being to the ones that suffer. Jesus hung on the cross naked and so do we. And that cross was present between my patient and I — even though I did not perceive it until I could smell it.

The silence we hear from God in our worst times might be the wordlessness of a God who is just hanging there with us, feeling what we feel, clawing and crying out with us while we shout, smelling what we smell.

My urge to be there for my patients is my desire to be there where Christ has gone already. I want to smell it with him. In his lectures on the book of Genesis, Martin Luther hovered over the words of Genesis 8:21 where Noah came off the ark to make sacrifices to God and that, “the Lord smelled the pleasing odor.” After some reflection on the nature of the odor and addressing speculation about just what made the sacrifice acceptable, Luther steered the discussion in a different way: “To me it seems that there is another reason for this expression, namely that God was so close by that he perceived the odor.”[1] God got close enough to Noah to smell what he was doing. For Luther, the good news was less that Noah had performed a sacred ritual correctly, but that God was so near to Noah that wrath turned into mercy and an everlasting promise.

While we try to keep God at the safe distance of our choices, Christ takes to the cross to be close to us in places of hurt and pain. He runs to the places we flee from in order to pay for them with everything he has. It’s hard to pretend that spirituality is something we consume when the object of our faith has already bought us and paid for everything with the righteous cash of his body and blood.

This is an exchange that I don’t create or facilitate as much as witness; like I did that day when I learned to just shut up and smell it. There are times when I can come and smell that stench and talk about the one who smells it with us, maybe even share another promise that comes from that same mercy. There are other times when respect and religious difference keep me from saying anything out loud. But as I get close enough to smell the stench, I know that I’m not the only one with my nose out. One way or another, Christ is always there, just a sniff away.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply