There’s no “Peanuts Ash Wednesday Special.” Nobody grew up watching a stop-motion Burl Ives saying, “Hey kid, you’re a sinner and you’re going to die.” Ash Wednesday doesn’t get anyone like Kris Kringle or Krampus. Starbucks doesn’t unveil any sin-themed soy lattes for Ash Wednesday. Christmas has been commercialized and loaded down with sweet-sounding Law. Easter has been sentimentalized by bunnies and butterflies and metaphors of springtime renewal.

The soot smeared on Ash Wednesday remains an unsullied message. There aren’t any Ash Wednesday office parties. There’s no marketing, no media, no movie tie-ins or product placements for Ash Wednesday. Nobody but Christians want anything do with talk about sin and death, which is a shame because, as allergic as our culture is to the ashes, what Christians do with them has more to do with love than any Nora Ephron movie.

When you do away with the concept of sin, the category of shame is your only alternative. Without sin, what’s wrong with me is simply and only what’s wrong with me. Leaving sin behind is lonely-making. Without a concept of sin, there is no correlative category of grace and you’re left only with what St. Paul would call the crushing accusations of the law.

Accused by the Law and in the absence of Grace, we self-justify. We perform and we pretend. We wear masks, just like Jesus condemns in the Gospel text assigned every Ash Wednesday. We project a purer, false self out into the world (which of course is just a way to shame others lest we be shamed first).

In an article entitled, “Excommunicate Me from the Church of Social Justice,” cultural studies scholar Frances Lee describes her decades-long exodus out of a shame-based conservative evangelical Christianity only to find the same sort toxic dogma practiced by progressives in the social justice-minded activist communities where she landed. Both communities, Lee argues, both sex-obsessed evangelicals and justice-driven progressives seek to justify themselves in the relentless pursuit to acquire purity according to the standards of their convictions.

Law, whether it’s law according to evangelicals or activists, always accuses, and Lee notes how the need in progressive social justice communities to be reckoned as pure produces a suffocating, shaming fear of being counted as impure:

[A kind of] social death follows after being labeled a ‘bad’ activist. When I was a Christian, all I could think about was being good, showing goodness, and proving to my parents and my spiritual leaders that I was on the right path to God. All the while, I believed I would never be good enough, so I had to strain for the rest of my life towards an impossible destination of perfection. I feel compelled to do the same things as a [progressive] activist a decade later. I self-police what I say in activist spaces. I stopped commenting on social media with questions for fear of being called out. I am always ready to apologize for anything I do that a community member deems wrong, oppressive, or inappropriate — no questions asked. The amount of energy I spend demonstrating purity in order to stay in the good graces of fast-moving activist community is enormous. Progressive activists are some of the judgiest people I’ve ever met, myself included. At times, I have found myself performing activism more than doing activism. It is a terrible thing to be afraid of my own community, and know they’re probably just as afraid of me. Ultimately, the quest for purity is a treacherous distraction for the well-intentioned.

What Frances Lee describes is what the Apostle Paul means when he warns that our well-intentioned efforts to acquire righteousness on our own lead to death.

It kills us.

Frances Lee escaped the toxic dogma of one community only to discover it again in an opposite sort of community. She left her evangelical church hoping to find respite from the demands of purity and relief from the suffocating pretense those demands require. In Paul’s terms, she fled the law, but the law found her. Yet she had been searching for Law’s opposite. Grace.

What Frances Lee found in neither, not in her evangelical upbringing nor among her progressive activists, is what the Church offers with oil and ash and a promise that sounds frightening at first, “To dust you came and to dust you will return.”

Ash Wednesday is the antidote to the treacherous distraction of the well-intentioned, because the medicine administered is not grim but, to those who know they are sick, it is the good news of the gospel. No matter how much booze you give up or how much Bible-reading you take on for Lent, Ash Wednesday isn’t about penance in a quest for purity. It’s not about needing to pretend when you fail to find that purity through your piety.

Ash Wednesday has nothing to do with your performance in life or your piety in religion at all. Ash Wednesday is about grace. Ash Wednesday is about freedom. Freedom from the fear of your impurity and freedom from the fear of death.

One could easily note a fair amount of cognitive dissonance with all the ashes. The day can look and sound like it’s exactly the sort of righteousness-chasing, purity-performing that Frances Lee critiques and, even worse, what Jesus Christ forbids. After all, in the Gospel passage assigned for every Ash Wednesday, Christ commands us to do the very opposite of what it appears we’re about to do. We will practice our piety before others; there is no ad space more public than your forehead. We will disfigure your face with oily ash, and then we’ll send you forth with unwashed faces not into the privacy of your prayer closet but out into the world where you will be tempted to repeat after the Pharisee, “Thank God, I am not like other men.”

Ash Wednesday’s promise of grace can get lost in the contradictions. But the most important point to remember about the ashy cross the church smears across the forehead is that it’s a cross.

The cross is absolutely irreligious. The cross is a reminder that the very best of our piety put God to death; therefore, on Ash Wednesday, Christians come out of the closet and with a soot scarlet letter freely admit that we are not just flawed and not just broken (that’s a romantic Christian word), but sinners. Sin is the only word that appropriately names our racism and our prejudice, our violence and apathy and avarice. We are the worst text messages that we send. We’re sinners.

The cross on our foreheads announces that before God’s Law we are failures. We have not loved God with our whole hearts. We have not loved our neighbor as much as we love ourselves, to say nothing of the love of our enemies. We have left undone the many things we ought to have done.

What Christians do with ash and oil does not violate Christ’s command against virtue-signaling because the cross signifies our vice. It brands us not as people who thinks we’re holy but as people who know our need. On Ash Wednesday Christians remember that — on paper at least — we are, in fact, the most inclusive people in the world. We are all sinners. Smudged or not smudged. Christian or not, activist or evangelical, none of us are clean.

None of us are pure. We are what Francis Spufford called the “International League of the Guilty.” There is no need for us to shame one another because between us there is no distinction. We are — all of us — sinners. And the wage paid out for sin is death. The wages of sin is death, the apostle Paul writes. Christians mix up their metaphors on Ash Wednesday, dust … ash … dirt … sin … death … because the wage for the sin we should mourn with ashes is a death marked by the throwing of dirt.

Ashen crosses on foreheads aren’t only a symbol of sin, but a symbol of your death to sin. That is, the cross is an oily and ashen reminder of our baptism. “To dust you came and to dust you shall return” — you’re gonna die — is grim godawful unless it presumes the prior promise of baptism that you have already died the only death that matters.

We will die, sure. To dust we came and, when our DNR kicks in, or the Medicare runs out, or our children lose their patience, we’ll just as surely return to the dirt. But the death that should haunt you is a death you’ve already died.

You’ve already been paid the wages your sins have earned. What you have done and what you have left undone, what you have coming to you has already come to you by way of the grave we call a font. By water and the Spirit, God drowned sinful you into Christ’s death. The death Christ died he died to sin, once for all. The death Christ died he died for your sins, all of them, once, and in his blood by your baptism all your sins have been washed away.

The dust on your forehead says, “You were dead in your trespasses.” But the cross on your forehead also says, “You have been baptized into his death for your trespasses.”

The wages of sin smudged on your head is good news, not grim news. Our sin, though incontrovertible, does not condemn. There is therefore now no condemnation. The seal of that promise is your baptism into his death. The sign of that promise is the symbol of his death smeared on your temple. And that promise should give you not only joy, it should — as Paul says — shut your mouth up. It should stop whatever words of judgment you might have on your lips because the ash marks us out as those who know that the Judge was judged in our place.

Of all the people in world the International League of the Guilty should be the least judgiest. “Where is our humility when we examine the mistakes of others?” Frances Lee asks in her essay, “There’s so much wrongdoing in the world. And yet grace and forgiveness are hard to come by in my circles.” Humility and grace and forgiveness shouldn’t be hard to find. At least not on Ash Wednesday. After all, the most important thing about the ashen cross Christians receive is that it won’t remain there forever.

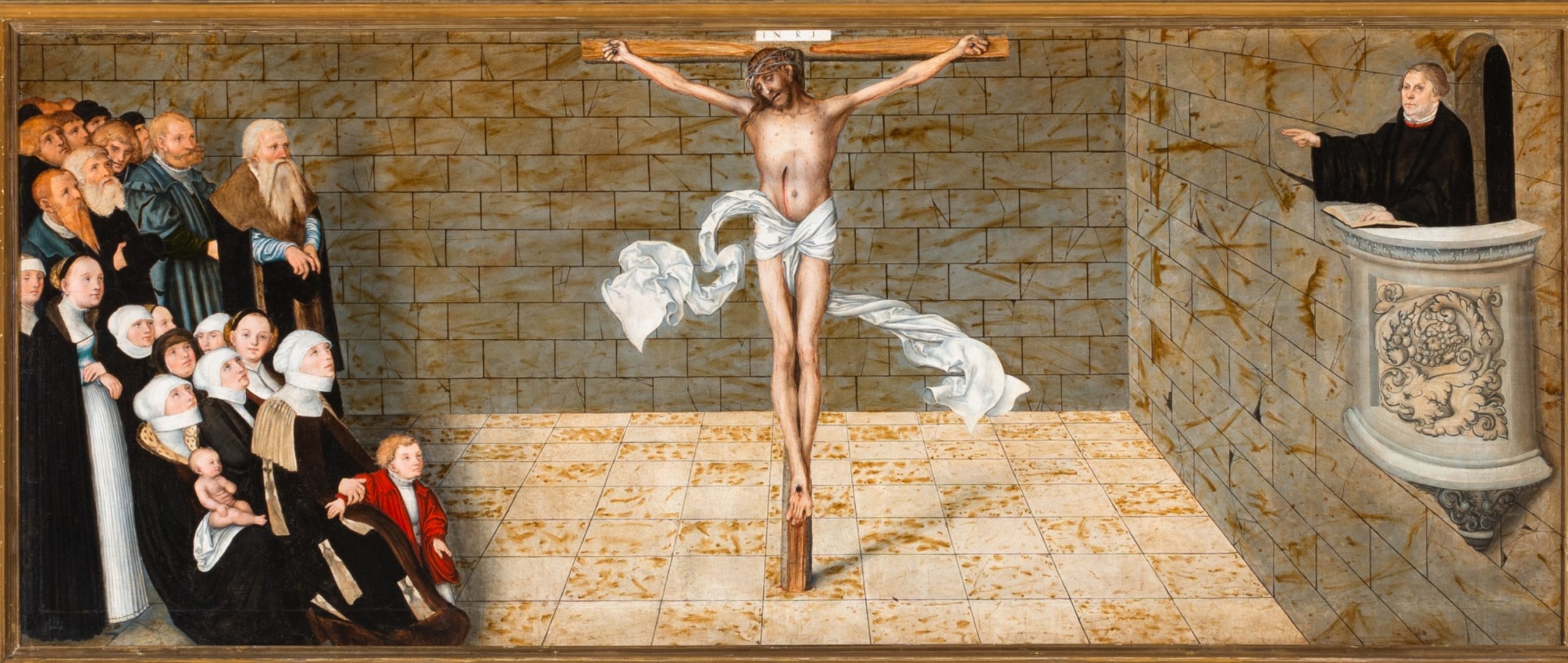

Our foreheads will be washed clean, both literally and metaphorically. Because we’ve not only died with Christ to sin, but in baptism we’ve been raised with Christ too, exchanging our sin for his purity. As Luther taught, “Christ Jesus you are our righteousness, and we are your sin.” In other words, however woke you think are, whatever righteousness you have, whatever purity you have never comes from you. Indeed, it had to come from outside of you as a gift. Just to make sure we didn’t miss the offense of that exchange, Martin Luther referred to the purity we do possess as “alien.” Our alien purity. Our alien righteousness. Alien — as in, we don’t have either, purity or righteousness, on our own.

The cross-shaped ashes of Ash Wednesday puncture the inflated anthropology our culture gives. The flattering self-image to which our culture would convert us is kicked it in the ash. As stern and old fashioned as it sounds, the ashes insist that “No, we’re not — none of us — basically good people who are doing our best so that God can do the rest.” We’re worse than flawed. We’re more than broken. “Nobody’s perfect” doesn’t begin to put it right. We’re sinners.

And that, ultimately, is how what Christians do today is actually about love. Ash Wednesday declares that the only true path to patience and empathy and comes by acknowledging the worst about ourselves, by claiming membership in the International League of the Guilty. Being able to say “I am a sinner who deserves to die” is the precondition to saying “I love you.”

COMMENTS

2 responses to “The International League of the Guilty”

Leave a Reply

This is a good essay, but note that Frances Lee’s pronouns are they/them.

[…] a CEO, When Perfection Isn’t Enough, Hope is an Ugly Cry, Thou Shalt Have a Thing, The International League of the Guilty, and Mark Driscoll and My Desert […]