Welcome to the fourth installment of author Ted Scofield’s series on everybody else’s biggest problem but your own. If you missed one or more of the previous installments, you can find them beginning here. New installments will be posted every two weeks, on Tuesdays.

Ann is a single, 50 year old entrepreneur. She invented a cost-efficient, biodegradable car battery that will transform the energy industry and measurably slow global warming.

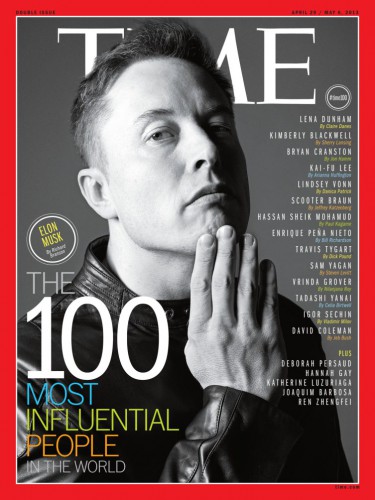

Tesla’s Elon Musk bought the patent from Ann; from the sale she netted $1 billion in cold, hard cash.

Tesla’s Elon Musk bought the patent from Ann; from the sale she netted $1 billion in cold, hard cash.

Ann promptly identified a group of respected, low-overhead charities that help starving children, cancer sufferers and others in genuine need, and she gave these charities $800 million.

Is Ann Greedy?

***

We’re examining a series of concepts that inevitably come up when the definition of greed is discussed.

Last time we looked at the most common concept, and today we move to a second commonly cited component of greed, utility. The premise: How we use our money plays into whether or not we are “greedy.”

I’ve posed the Ann scenario and bottom-line question to a diverse group of individuals and audiences over the past several months, and I know many of you have an immediate, visceral answer to my question.

“No! Ann is not greedy! She gave away 80% of her money, a whopping $800 million!”

“Yes, she is greedy! No human being needs $200 million!”

When pushed about the residual $200 million, the No Camp almost always offers two rationales: 80%!! And, “she earned it, it’s her money, she can do whatever she wants with it.”

“Okay,” I’ll respond. “So say Ann gives 2% of her billion to charity and spends hundreds of millions on houses, planes, yachts and jewelry – whatever she wants.”

The typical response is: “Only 2%? She’s greedy.” My follow-up question: “So 80% is enough to avoid the dreaded greed trap, but 2% is not. What’s the cut-off, the magic number? 10% (the Old Testament tithe)? 20%? 50%?”

“Well…” And silence follows.

When pushed about the seemingly generous 80% and $800 million, the Yes Camp inevitably repeats emphatically “No one needs two hundred million dollars.” Period. Case closed.

“Okay, “I’ll respond. “So how much of her money must Ann give away before you’ll say she is not greedy? How about 95%? Can she keep $50 million?”

Answers vary tremendously, with the honest “I don’t know” being the most common. Less common are hard numbers, but I’ve heard everything from “all of it” to $100 million.

One eager college student said confidently: “Ann should give all of her money to charity because we need people like her motivated to invent more amazing things.”

To the other I asked: “Why can she keep $100 million?”

“Well … because it just seems fair.”

So where does that leave Ann? Should she rest easy at night, content she has done the right thing?

Obviously it depends on whom you ask.

***

Utility. Most all of us agree that how we use our money – what we do with it – is relevant to greed. But can we reach a consensus on what that relevance might be? Can we quantify utility, apply it fairly to ourselves as well as the guy next door? Personally, I don’t want to be greedy. How much of my money should I give to those in need? How much should you?

It’s not purely a hypothetical question by any means. Non-billionaires like you and me often struggle with how we use our money. Are we giving away enough?

And, of course, the charitable giving of politicians and wealthy folks is also oft-scrutinized. Let’s look at a few high-profile examples.

In 1997, media mogul Ted Turner donated $1 billion to the United Nations, leaving his net worth at $2 billion.

Years later journalist John Stossel questioned Turner on his $2 billion, who replied with difficulty: “I’m doing all I can. And still keep enough for, you know, make sure that my grandchildren make it, can get through college.”

Stossel then suggested that $2 billion was more than enough, to which Turner answered: “It’s not enough.” Turner then questioned the safety of banks, the US government and even Social Security.

Stossel also interviewed the now late Dan Duncan, net worth $7.5 billion and on the Business Week list of most generous philanthropists. Duncan gave away 2% of his net worth. When queried about keeping 98%, Duncan explained he would give away more at a later time, because “if you’re one of the gifted people that can actually make money, people receiving it are better off if you keep it to get a lot more later on.”

Finally, how about those Koch brothers? Few names elicit as much righteous anger and downright bile as “Koch.” A few headlines:

- The Koch Brothers: Godfathers of Greed

- The Koch Brothers Are Waging War Against the Poor

- “Greedy Lying Bastards” Review: The Koch Brothers’ War on Truth

But the controversial brothers don’t only use their billions for lobbying Congress and funding political interest groups. Last year the Kochs donated $25 million to the United Negro College Fund. The beautiful new fountains and pedestrian plazas outside the Metropolitan Museum of Art? $65 million, paid for by David H. Koch (who also gave $100 million to Lincoln Center in 2008). The list goes on and on: Prostate Cancer Foundation ($41 million), Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center ($150 million), Anderson Cancer Center ($25 million), MIT ($139 million), Jaffe Food Allergy Institute ($10 million), etc. etc.

So are the politically conservative Koch brothers the “Godfathers of Greed”? How about liberal stalwart Ted Turner, who today is worth $2.2 billion? Is he greedy? I imagine your answers depend on only one thing, your personal political agenda.

So are the politically conservative Koch brothers the “Godfathers of Greed”? How about liberal stalwart Ted Turner, who today is worth $2.2 billion? Is he greedy? I imagine your answers depend on only one thing, your personal political agenda.

But let’s not fixate on the greedy/generous billionaires. Let’s return to reality, to you and me. How much of our money should we be giving to the less fortunate?

Many of you probably share my desire: We want a number, an answer, something concrete with which we can agree or protest.

Unfortunately, despite months of research, study and conversation, I haven’t found it.

I believe this concept of utility and its relation to greed – how we use our money to help others, or not – is as intensely personal as our overall definition of greed.

As I said in the introduction to this series several weeks ago:

Each of us individually defines greed in such a way that each of us, individually, is not greedy. And as our unique financial situation evolves, so does our unique definition of greed, leaving us forever outside its grasp.

Last week I ran the hypothetical Ann scenario by a friend of mine: “So Ann earned a billion and gave away 80% of it. Is she greedy?”

“Well, I aspire to be Ann, and if I gave away 80% of anything, I know I would not feel greedy.” Thoughtful pause. “But, then again, at this stage I’d probably be satisfied with $200 million cash, so maybe I would give a lot of it away.”

“You’d be satisfied with $200 million? Why is that?”

“With $200 million I could get everything I want and never work again. I’d be satisfied. Maybe that’s what Ann was thinking.”

And that, not coincidentally, is the perfect place for us to end today’s discussion, because next time the topic will be another commonly cited yet murky attribute of greed, satisfaction. Are we greedy if we’re not satisfied with what we have?

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eih67rlGNhU&w=600]

COMMENTS

13 responses to “Everybody Else’s Biggest Problem, Pt 4: Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?”

Leave a Reply

To claim that Ann should not keep $200M and should give it away is to assume that others know better how to allocate the $200M than does Ann. Maybe Ann will invest it and give away $1M (5%) in perpetuity. Isn’t a program that guarantees a $1M gift each year a godsend? Ann’s done a seemingly great job of allocating her resources so far. Why shouldn’t she continue?

Wow. Now there is a foundation for preventing cancer caused by lying down? 😉

For purposes of the hypothetical, I assume Ann is spending her remaining $200M on stuff she wants. Is she greedy? My knee-jerk reaction was with the “yes camp.” Why would anyone need that much money? But after reading the article, I’m no longer sure and see the argument from the other side. Greed is illusive, deceptive, unique. Our culture feeds us mixed messages about materialism and charitable giving.

This is what really grabbed me, the billionaire who said: “if you’re one of the gifted people that can actually make money, people receiving it are better off if you keep it to get a lot more later on.”

REALLY?!? SERIOUSLY?!? Tell that to starving children or a battered woman sleeping in a box on your street corner. (You know the one, the human being you drive past or step over on the way to buy a $5 soy latte.)

Tom, that quote really shocked me too, and I had to resist the urge to say exactly what you did. I figured readers would get there without my prodding.

Brad & Liza, yes, for purposes of the Ann scenario, I assumed Ann is not using the remaining $200 million for charitable purposes.

LT, good catch. Fixed.

Is a possible definition of greed, if I want something for myself more than I want it for someone else? Fantastic series of posts!

Some of the greediest people I’ve ever met had very little means. I can’t call Ann ‘greedy’ because she has kept a lot of what she earned. Are the people who took the pledge to give away half of their net worth also greedy? The Gates are greedy because they aren’t giving it all away now? That’s hard to follow.

Em7srv, I see where you’re going with that definition, but I’d suggest it suffers from two problems. First, how could we apply it collectively? It remains a definition subject only to the desires of the individual. Second, from a very practical standpoint, if a single mother with 4 kids who lives in a studio apartment wants a 2 bedroom house for herself more than she wants it for her childless sister, is she greedy? Finally, I’m thrilled you’re enjoying the series! Please spread the word!

Brad, you are firmly in the “No Camp” and I do not disagree with you. The “Yes Camp” would ask why any single human needs $200 million. Bill Gates’ net worth is $80 billion. If he wrote a check tomorrow for the full 50%, he’d still be worth $40 billion. The “Yes Camp” focuses on that hard number, not the percentage.

My goal is not to say one group is right and the other wrong, but to argue that greed is unique among the human vices/sins/frailties. Collectively, we can not define it; we can not agree on what it is. We say greed is a problem, but it’s not my problem. We are lost.

Greed is everyone’s problem, even the homeless person begging on the street. We are never satisfied with what we have, which is already too much, The root of greed is disbelief. I don’t trust in my Creator so I have this insatiable desire to want. Insecurities about in our idol-making lives. That’s the crux of this author’s search. I’m greedy, you’re greedy. I’m a racist, you’re a racist. The list goes on. I’m a sinner, you’re a sinner. Thank Jesus for His grace alone that rescues us.

This is a great discussion from a great source. Thank you for initiating it.

I want to be a rich “sinner”, not a poor one, since I’m a “sinner” anyway, and “human nature is evenly distributed” and all that blah, blah, blah. I’ll even give a lot of cash to my church and favorite “non-profits” too, as long as I am still rich after the giving.

Mike, absolutely, the biblical response to greed is idolatry. Among many other passages, Colossians 3:5 is crystal clear. But is “idolatry” a workable cultural definition of greed? Could a like-minded group of devout believers agree on the parameters of this form of “idolatry”? I suggest the answer to both questions is No.

Brad, thank you!

Michael, my instinctive reaction to your all-too-accurate comment is Mark 12:41-44, which reads: “And [Jesus] sat down opposite the treasury, and began observing how the people were putting money into the treasury; and many rich people were putting in large sums. A poor widow came and put in two small copper coins, which amount to a cent. Calling His disciples to Him, He said to them, ‘Truly I say to you, this poor widow put in more than all the contributors to the treasury; for they all put in out of their surplus, but she, out of her poverty, put in all she owned, all she had to live on.'”