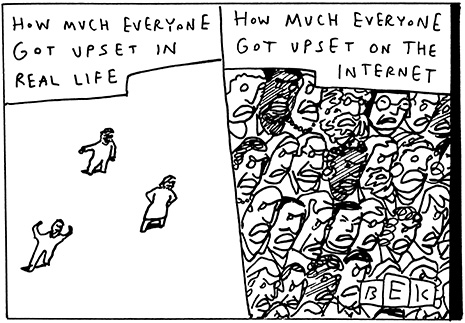

I’m sure I’m not the only one who thought people were joking at first with the whole #Cecilthelion fracas last week. I was traveling, so I only heard snippets of what had gotten people so upset. Once I realized they were serious, surely I was missing something. Alas, even after reading up on the admittedly grotesque incident, the whole thing feels too much like a send-up of internet outrage, parodic in both subject and intensity, like something Black Mirror might do. The joke was on me, I guess. Until I remembered Tim Kreider’s immortal diagnosis of the phenomenon:

So many letters to the editor and comments on the Internet have this same tone of thrilled vindication: these are people who have been vigilantly on the lookout for something to be offended by, and found it…

Obviously, some part of us loves feeling 1) right and 2) wronged. But outrage is like a lot of other things that feel good but, over time, devour us from the inside out. Except it’s even more insidious than most vices because we don’t consciously acknowledge that it’s a pleasure. We prefer to think of it as a disagreeable stimuli, like pain or nausea, rather than admit that it’s a shameful kick we eagerly indulge again and again…

I’d say “amen” if I didn’t think it’d place me in an equally judgmental position. At least, that’s (sort of) what James Hamblin argued in a terrific write-up of the Cecil-related outpouring for The Atlantic. In his view, the event illustrated the ‘pleasure’ inherent in righteous indignation. Since the true seed of the outcry has to do with moral justification (his term is “validation”), the emotions are not allowed to linger on the event itself. We cannot all be equally upset–that would deny us the affirmation of specialness our anger demands. Instead, it quickly becomes a question of degree, where people start one-upping themselves in search of the highest possible moral ground, clamoring over one another for supreme indignation even though they’re ostensibly on the “same team”. It becomes a contest, in other words, where identity is at stake. Whose outrage is the most pure? The most righteous? Whose devotion to the, er, undercat the most unassailable? Thus the absurd escalation, which, ironically enough, only perpetuates the bad feeling, ignoring logs and splinters alike:

I’d say “amen” if I didn’t think it’d place me in an equally judgmental position. At least, that’s (sort of) what James Hamblin argued in a terrific write-up of the Cecil-related outpouring for The Atlantic. In his view, the event illustrated the ‘pleasure’ inherent in righteous indignation. Since the true seed of the outcry has to do with moral justification (his term is “validation”), the emotions are not allowed to linger on the event itself. We cannot all be equally upset–that would deny us the affirmation of specialness our anger demands. Instead, it quickly becomes a question of degree, where people start one-upping themselves in search of the highest possible moral ground, clamoring over one another for supreme indignation even though they’re ostensibly on the “same team”. It becomes a contest, in other words, where identity is at stake. Whose outrage is the most pure? The most righteous? Whose devotion to the, er, undercat the most unassailable? Thus the absurd escalation, which, ironically enough, only perpetuates the bad feeling, ignoring logs and splinters alike:

The Internet has served to facilitate outrage, as the Internet does: the hotter the better. And because the case is so visceral and bipartisan in its opposition to Palmer’s act, few people stepped in to suggest that the fury, the people tweeting his home address, might be too much. That argument wins no outrage points. Instead, the people who hadn’t jumped on the Cecil-outrage bandwagon jumped on the superiority-outrage bandwagon. It’s a bandwagon of outrage one-upmanship, and it’s just as rewarding as the original outrage bandwagon…

The Internet launders outrage and returns it to us as validation, in the form of likes and stars and hearts. The greatest return comes from a strong and superior point of view, on high moral ground. And there is, fortunately and unfortunately, always higher moral ground. Even when a dentist kills an adorable lion, and everyone is upset about it, there’s better outrage ground to be won.

Many people are drawn to defend nature and underdogs (even when they are apex predators) and to hate wealthy, lying, violent dentists. But even more than that they are drawn to feeling superior and appearing wise, and being validated accordingly.

If that’s not a biblical anthropology, I don’t know what is. Add to the mix a deeply unsympathetic perpetrator, and the Old Testament parallels get downright uncomfortable: if we have someone at whom we can point the finger and thereby heap our collective guilt and shame on, maybe they will absorb or at least distract us from our own for a bit. The human race loves a scapegoat, after all.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eFo9FRVxSUM

Anyway, Hamblin’s assessment reminded me of two other observations that surfaced this week, albeit from opposite sides of the political spectrum. The first came from Camille Paglia, whose interview with Salon Ethan quoted on Friday. It’s almost as if the lady is incapable of giving uninteresting commentary (aggressively contrarian at times, sure, but never boring). This is from the section where she goes after the culture of snark (e.g. Jon Stewart) and decries the influence of radical atheists, whom she describes as adolescent. But it was her characterization of the social media generation that seemed especially relevant:

“All the great world religions contain a complex system of beliefs regarding the nature of the universe and human life that is far more profound than anything that liberalism has produced. We have a whole generation of young people who are clinging to politics and to politicized visions of sexuality for their belief system. They see nothing but politics, but politics is tiny. Politics applies only to society. There is a huge metaphysical realm out there that involves the eternal principles of life and death… Young people have nothing to enlighten them, which is why they’re clinging so much to politicized concepts, which give them a sense of meaning and direction.”

Meaning, people of a certain generation are dying for meaning and, lacking any more substantive metaphysical framework, will latch onto basically anything they can to get it–especially if it approaches their pre-existing sympathies, political or otherwise–even something as outwardly inconsequential as the Cecil travesty. In fact, the absurdity of this one is why it exposes the psychology underneath so nakedly: Moral outrage fills a psychological need. It allows a person to feel like they matter, especially when they’re afraid that they don’t. And thus Internet outrage almost always has more to do with its subject than its object. We come to identify with it–to rely on righteous anger for our validation, justification, the measure of our virtue, what have you–so that when it’s taken away, when public opinion finally shifts in our direction, or the court overturns the decision we found so unfair, well, the outrage has to find a new target if we are to feel like our breaths still count. Come to find out, fury does not always discriminate so astutely. It has a brain of its own.

Not only does rage have a brain of its own, it tends to follow a discouraging if all-too-predictable pattern, as Alan Jacobs’ suggested in his brilliant discussion of philosopher Charles Taylor’s “Code Fetishists and Normolaters” dichotomy. It’s one of the better things I’ve read this year.

Jacobs–with the help of another social media firestorm (Justine Sacco) as well as Leo Tolstoy–makes a compelling case for Taylor’s thesis that society consists of two warring factions, moralists and antinomians, one of which gives birth to the other. These factions take both religious and non-religious forms, and while on the surface they look different, they are in fact quite similar in their allegiance to “rules” (or principals) over people, something that the disembodiment of technology makes much easier.

It’s not a particularly long piece, nor as convoluted as it may sound, so do go read the whole thing. The following is hopefully enough to get the gist though:

In an absolutely vital essay called “The Perils of Moralism,” [philosopher Charles] Taylor explains that “modern liberal society tends toward a kind of ‘code fetishism,’ or nomolatry. … Code fetishism means that the entire spiritual dimension of human life is captured in a moral code… The attempt was always to make people over as more perfect practicing Christians, through articulating codes and inculcating disciplines.” Eventually “the Christian life became more and more identified with these codes and disciplines.” But once that had happened, the Gospel itself became dispensable: all we had to do was to extract the rules from it, and the “values” that produced them, and we were good to go. Thus arise figures who use the codes extracted from Christianity against Christianity: Voltaire, Hume, Gibbon.

And thus also arises an antinomian counter-movement: “Modern culture is marked by a series of revolts against this moralism, in both its Christian and non-Christian forms. … These form, for instance, the central themes of the Romantic period.”

Thus modernity is characterized by constant tensions and frequent eruptions of hostility between two great opponents, the antinomians and the code fetishists. Most of the fights that afflict social media today are versions of this conflict: just think of the recent skirmishes between the self-described free-speech advocates on Reddit and the opponents whom they refer to as SJWs (Social Justice Warriors).

I think the key lesson to be drawn from Taylor’s account is that code fetishism produces antinomianism: antinomians are people who get frustrated by the code fetishists’ relentless policing and disciplining of disagreement—which the fetishists do because they are trying to build a more just society and think that codification and enforcement of rules is the only way to do it—and believe that a simply rejection of rules is the only way to resist. That is, both sides agree that morality is a matter of rules…

But what if this is a false dichotomy? What if the code fetishists and antinomians are both wrong, and wrong for the same reason: because they have unwittingly accepted the false idea that “the entire spiritual dimension of human life is captured in a moral code”?…

I think we can see that our dominant social media have a strong tendency to reinforce the normolatry-antinomianism dichotomy, and to obscure the need for “networks of living concern.” To search Twitter or Facebook for people using words you don’t like, or using important words in ways you don’t like; to scroll through a list of tweets or posts that employ a particular hashtag with an eye towards the absurd or offensive; to seek out particularly provocative tweets or posts in order to see how outrageous the replies are—these are the characteristic acts of the code fetishist. I pray you, avoid them.

To be perfectly honest, most of what goes through my mind after reading Jacobs’ and Taylor’s words is the abstract code I want to extract from them: something about rebellion and conformity being flip sides of the same Ought-sized coin, or about the way anger inevitably turns grace into a law. Whether or not such thoughts have any grounding is beside the point–they comprise a validation mentality all the same, one that seeks its own moral high ground/superiority and is bent on its own dehumanizing ends (which are my own), consciously or not.

I suppose that leaves only one possibility open, hope-wise. Not just for me and you, but for Walter Palmer and his critics (and their critics), that is, mob and quarry alike. I’m talking about something that doesn’t require us to secure our own meaning. In fact, it doesn’t require anything of us at all–except, perhaps, our need, which is the only entry point for true meaning anyway. I’m referring to the hope of forgiveness. Initiating forgiveness, yes, atoning forgiveness, aimed at those incapable of conceptualizing it correctly.

It sounds like abstraction, I know. And it would be, were this forgiveness less a What than a Who. Or, as Jacobs so beautifully puts it mid-way through:

Our world looks very different if what matters is not the code we can abstract from a given situation but the situation itself—or, more specifically still, the utterly particular person who stands in front of us.

COMMENTS

33 responses to “Are You Washed in the Blood of the Lion?”

Leave a Reply

DAVID THIS IS SO GOOD. Like, so good. And I’m pretty sure my roller derby name is Righteous Indignation. Thank you for writing this.

Great assessment! This really helps sort out a lot of issues currently in the social realm where we focus more on being on one of two sides than what the sides actually mean. Very nice.

I’m really trying to understand. . .

So let me return to the simplist example. Cecil. The beginning of this essay (and maybe I’ve just read badly) sounds a little like, “Oh my, people are upset about THAT? Who could possibly be bothered to care?” But I’m happy to hear I’ve simply misread.

Is it possible to say, “Hearing about Cecil is painful and disturbing. An animal was killed for no good reason, suffered on the way, and now I’m learning. . . this happens more often than I thought it did, often enough that lions are in in serious short supply. Its surely not the only painful truth about the world, but it is yet another one I’m just learning about.”

And follow that with: “Wow, I hope vigilantism doesn’t ignite and someone kill or cause injury to that dentist or his family. Something has got to be seriously wrong with a human being to take pleasure in death, though I don’t pretend to know what it is. I hope he gets help. I hope he stops. I hope others who do this sort of thing stop. And perhaps we need some further legislation, and the organizations that are working for human and environmental well being in Zimbabwe. . . I hope they have the resources they need.” (And much more thinking along those lines, if that’s my calling. And I never know the answer to that until I’ve got at least this far.)

Is that giving this too much thought? Is it another form of false. . . righteousness? Just more subdued?

I’d also admit that before I calmed down to “this is painful and disturbing,” even on my better days, I’d first move through anger. Always wrong?

Long ago I read Garrett Keizer’s The Enigma of Anger, which has haunted me since. I think he’d find a place for it in this discussion, be he is also a thoughtful man, who knows that anger has serious limits.

Hi Tanya- thanks for sharing your thoughts. Kudos for thinking hard this subject- I think the point of this essay (and the essays DZ linked to) has to do with that very act of thinking hard.

The critique is that digital lynch mobs not only avoid thoughtful reflection, but also turn that anger toward those who seek thoughtful reflection. Not only this, but there’s an equal-but-opposite digital lynch mob that forms in rebellion against the first mob. Hence, the conversation becomes “Poor Lion, Evil Dentist” vs. “Dumb Lynch Mob, I Won’t Join In,” leaving no room for that thoughtful middle ground. This forming of lynch mobs has a lot to do with a sinful heart needing to justify itself as “good/worthy/righteous,” and thoughtful reflection get in the way of that.

So the point of the essay, I would summarize, would be this: can you imagine yourself becoming the target of an online lynch mob for something that you’ll do or something you have done? If not, that’s probably a sign that the anger is more related to self-justification than it is related to grief. Is that helpful?

Yes, I think so! Still mulling on the fact that calm “on the one hand, on the other hand,” thinking doesn’t come first — something more visceral does. Disgust, grief, — but pre-internet that might have had more time to cool and not gone directly to print as it now does. And frankly, unflappable calm and “thoughtfulness,” as an early response–not sure I’ve seen this much, except as a form of detachment.

Props for the No Code cover, first of all. Such a gem of a record.

This brings up the question of whether our spheres of concern are artificially expanded by the reach of the digital world. We hear about far more than we otherwise would and cannot respond to it on a human level so we’re relegated to these cartoonish outbursts. Trying to inflate ourselves to act out our part in the rules/rebellion battle on a global level when we were only ever made to act on a human level (which is necessarily local because we are local creatures, not global). With too much knowledge comes too much attempt to take responsibility.

Yeah. I think you’re on to something. Could be not our responsibility, but we still love the smell of the fight. But it requires a moment of thought, no? Because that’s also our best dodge. You know the story: the priest and the Levite –had other responsibilities. At least I’m going to assume they weren’t just mean. And there must have been a moment when the Samaritan thought . . . is this on me? –before he decided it was.

And that impulse to relate only to what we can “on a human level,” voila, hardly gets activated if we keep our focus narrow, our plates full. (And our neighborhoods really, really small.)

I’ve been mulling this over and I definitely agree that a limited sphere of concern can cut both ways (either helpful for focus on achievable ministry, or an easy out for no practical ministry whatsoever). However, in the parable you mentioned, the priest and the Levite stepped over an actual broken body in their path. It was a very bodily scenario, and one that begs us to have our eyes open for the suffering and injustice in our very midst. So maybe if we were more alert to the need in our midst, we’d have less energy to expend on digital outrage flung to distant places?

Thesis: keeping our concern to a human level isn’t an excuse for doing nothing. That would be a miscarriage of conscience just as much as fuming [and shouting] about every cause for outrage far and wide. It’s not that I don’t care about the far-flung things, but that I accept some kind of responsibility for my locality and I hope someone is present elsewhere while I am present here. At some point, we have to acknowledge our limits, and then hope to do good within them. I realize I’ve just come to the very precipice of the Serenity Prayer.

(And our neighborhoods really, really small.)

Most everything in our culture is either explicitly or implicitly against this kind of smallness (at least in the urban/academic sectors–because the university is more or less a training ground for urban life). A local neighborhood is dwarfed by the scope of a globalized economy and all it implies. But, I’m not entirely convinced such a disproportion automatically makes folly of tending to your human locality. It’s tempting to want to do more, to have more and broader influence, but maybe that temptation deserves closer scrutiny than the speed of commerce and trying to keep up has allowed.

Sorry this got away from me, thanks for your response.

This feels like one of those things that both sides seem right to me.

Yes, throwing up outrage about every little thing half a world away seems pointless and energy-sapping. On the other hand, the number of Ivy-League educated young adults I’ve heard say, “I just don’t have time to care about. . . reading the newspaper, voting, or doing pretty much anything besides finishing my computer science degree and enjoying my wine-tasting seminar” is well, not inconsiderable. Maybe they’ve zoned out because they’re overwhelmed when they do occasionally look up. You might be right. But a university community, I’d argue, is often the place we hone our head-down-keep-your eyes-in-own-lane methods. Ask an electrical engineering professor what he knows about the role of Conflict Minerals in the Congo. Quite possibly her field of interest is so narrow she won’t have an opinion.

I’d add that some of the things that need our attention — aren’t just local, body in the street in front of us– and won’t be. Climate change. Ocean acidification. Unless we develop the imaginative capacity to see that a human being will be injured –perhaps a continent away, or a decade from now, we may not act out of compassion when we choose our Chilean Sea Bass.

Male lions kill their own cubs to show dominance. I’m sure Cecil killed his share. Some folks show dominance with expensive animal trophies, others show it through moral indignation, others through above the fray social analysis. Maybe it has more to do with evolutionary biology than with law/gospel.

…..and 53% of Americans haven’t heard about the Planned Parenthood videos. We want to be indignant about something that matters, but simpleton media keeps us indignant about the less significant.