Full disclosure: the point of this article is to get clicks. Lots of clicks. Because, love him or hate him, the Canadian psychology professor and clinical psychologist Jordan Peterson gets clicks. And despite all our talk at Mockingbird about not keeping score, Google Analytics is real and we are sinners and clicks are the currency of the blogging business.

Seriously though, if we are serious about connecting the gospel to the realities of everyday life, right now, everyday life involves Jordan Peterson.

If you’re not familiar, the professor and psychologist rose to internet infamy for his staunch opposition to government mandated use of non-gendered pronouns for transgender students (his opposition was not the pronoun part, but the government mandated part). It turns out Peterson has spent decades studying totalitarian regimes and “human malevolence,” and his opposition to government mandated speech has its roots in his study of the psychology of communist dictators. Since his Youtube videos on the issue of government mandated speech went viral, he’s been greeted by sell-out crowds and protesters on his speaking tours, his podcast and Patreon have blown up, the Op-Ed pages in all the major papers are raising their eyebrows, and his latest self-help tome “12 Rules for Life” is getting translated into 34 languages.

Reading up on Peterson, I was surprised at how systematic and organized his worldview and lectures are, a testament perhaps to his thorough commitment against the reign of chaos. Despite his controversial persona, there are some interesting ways a Mockingbird reader might connect with his writing. Nobody in 2018 is as convinced of original sin as Peterson, even if he uses that more clinical term “malevolence.” At the same time, the man gives the early church fathers a run for their money when it comes to allegorizing the bible into awful interpretations. Saint and sinner, I suppose, just like the rest of us. Keeping this in mind, here’s a quick guide to “Petersonism” and the works that underpin it.

The Primacy of Suffering

At the core of all Peterson’s work is the idea that life is suffering. That suffering comes in two forms. The first is chaos–suffering caused by that which is outside human control, like volcanoes, drought, random car accidents, and sickness. The second is malevolence: intended harm that comes from humans, whether interpersonal malevolence between people (violence, theft, sabotage, racism, all the external bad stuff) or intrapersonal malevolence (poor choices, self harm, addiction, selfishness). It’s an existentialist argument, and Peterson regularly brings in heavy hitters like Nietzsche, Dostoevsky, and Kierkegaard to make his points.

Really, to hear Peterson talk about malevolence is to hear a preacher discuss Original Sin. The two are extremely close concepts. One might recall the exchange between Princess Buttercup and her lover Westley in the famed 1987 movie The Princess Bride. As the princess weeps over her dead former love (who is actually standing in front of her, disguised), Westley refuses to give her pity, believing her to be unfaithful. “You mock my pain!” exclaims Buttercup in tears, and Westley responds angrily, saying, “Life is pain, highness. Anyone who says differently is selling something.” Peterson would agree with Westley’s response (and frankly, he would appreciate the tone of it as well). The starting place for this system is that life, by our own cause and by outward causes, is pain.

The Significance of the Individual

For Peterson, it is of primary importance that people are evaluated and examined as individuals. To him, it is the pinnacle of Judeo-Christian thought, the source of whatever human flourishing has occurred in the global west. Peterson is haunted by the writings of Russian author Alexander Solzhenitsyn, who wrote extensively about his brutal life as a Soviet work camp prisoner. He is convinced that when people are treated as groups and not individuals, as they were in Stalinist Russia or Maoist China, very bad things happen and millions of people die. Peterson insists that when people are reduced to only a group identity–be that race, gender, religion, or nationality–interpersonal human malevolence thrives.

Tune in to PZ’s podcast for a breakdown of those ideas from a Mockingbird perspective. No joke, it’s been a recurring subject on the podcast since at least October of 2013 (ep. 156 – five years ago!). The oft-quoted adage from Tim Kreider, “if we want to be loved, we must submit to the mortifying ordeal of being known,” gets to the heart of the matter. Human beings reduced to a category cannot be fully loved unless the love pushes through the collective marks into the real self. And while the historians and political scientists can argue whether individualism is the great gift of the west, the theologians would do well to take notice that pastoral care and preaching are equally as ineffective unless it can push through to that place of the real self.

The Inevitability of Hierarchy

According to Peterson, wherever human beings espouse values, they build hierarchies around those values. They can’t not do so. Hierarchies allow us to keep malevolence and chaos at bay with order and trust. If a group holds the virtue of honesty as a key value, for example, there will inevitably be a hierarchy where those who are perceived as honest will have more access to resources and opportunities than those who are perceived as dishonest. The same goes for other virtues such as kindness, temperance, or charity.

While those hierarchies may be easily understood, problems arise when some values create less appealing hierarchies. Working hard, for example, is an American value, and the hierarchy gives those who work hardest the most resources and opportunity. So much good comes from this value–industry and innovation are great things! But when a hard worker becomes injured, develops a mental illness, grows old, forgoes family obligations, loses community, or otherwise loses the ability to work hard, they fall down the cultural hierarchy. For Peterson, the political Right exists to enforce the hierarchy and keep chaos at bay, while the Left exists to challenge the hierarchy and care for those at its bottom. Every hierarchy has winners and losers, and they are both necessary to keep chaos at bay.

Peterson’s hierarchy is not too different from our conversations about law, be it God’s “big L” Law or the “little l” laws of our lives. We might easily say, with interchangeable language, that Instagram is a realm with hierarchies, or Instagram is the realm of the law, where the values of beauty, photography, and style are affirmed values, confirmed by a hierarchy of likes, follows, and comments of affirmation. The hierarchy and the law both say, “succeed or be downcast.” It’s one of the best ways I’ve personally heard a non-Mockingbird discuss the dynamics of the little-l laws at work in the life of the human being.

Peterson has made much of lobster physiology in his lectures, and so the sea creature has become a Peterson meme of sorts.

The Primacy of Archetypes

Peterson’s psychological training has led him to the importance of narrative, particularly the Jungian arch-narratives that have existed throughout human history. You know all that stuff about Story that churches are into, about how every life has a story and God’s writing it, yada yada? For Peterson, he’s less interested in who writes the story, and more interested in how we connect them into the great stories of human anthropology. Are you on the hero’s journey, acquiring skills, mentorship, and knowledge to face down chaos and bring order in the world? Or are you surviving the flood, when chaos is all around you and you’re fighting tooth and nail to survive? Or maybe you are the fool being set up for a great and cataclysmic fall (though I certainly hope not)!

Maybe you are the blind man regaining sight, or maybe you’re a rich young ruler looking for eternal life. Maybe you’re discovering a solution that comes from an unlikely source like Nazareth, or maybe you’re even going through a death and resurrection. It’s not as if Peterson is wrong in finding ourselves in old stories, necessarily–it’s more that he has a wider storybook than we do for telling those stories. He’s equally as able to pull from Genesis as he is from stories of Marduk in ancient Mesopotamian religion.

Put it all together and you get a framework for Petersonism that looks like this: everyone’s world is defined by chaos and malevolence and those things act together in unique ways for each individual person. The task of every person then, individually, is to gird their loins, slay their demons, and either make order out of chaos or bring chaos into a tyrannical order. That quest will provide meaning and the energy to thrive and find meaning in that world marked with suffering.

And, to listen to him say it, anyone who doesn’t see this reality is probably a weak person or a neo-Marxist postmodernist who would tear down the established walls of order and let chaos reign free! Paging Dr. Noble, Dr. Noble to the psychology department please! No wonder the man has so many haters. Never trust a swearing Canadian (unless he’s in a hockey fight).

So there’s a long road Dr. Peterson and St. Paul could walk down together: three cheers for the return of low anthropology to the public square again, and three more for a renewal of interest in Dostoevsky and the Book of Genesis!

At the end of the day, however, Peterson’s is a road that ends like many others: with bootstraps and self-improvement. Granted, it’s a self-help rooted in neuroscience and the best psychology to date, so there may actually be some help for the self in his world. Still, when it comes to the question of salvation by works or salvation by rescue, there is a fork in the road where Dr. Peterson and St. Paul would part ways.

Take, for example, Peterson’s focus on the archetype of The Hero’s journey. There’s a remarkable lack of space in Petersonism for people who do not complete their hero’s journey. There exist some dragons–death chief among them, but addiction and illness are runners up–that are ultimately unslayable for many.

Take, for example, Peterson’s focus on the archetype of The Hero’s journey. There’s a remarkable lack of space in Petersonism for people who do not complete their hero’s journey. There exist some dragons–death chief among them, but addiction and illness are runners up–that are ultimately unslayable for many.

Peterson’s understanding of hierarchies invokes the famous 1973 parable by Ursula K Le Guin, “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas.” It’s a tale that describes a peaceful and verdant utopia named Omelas on the first day of their summer festival. This idyllic society has no police, no clergy, no slaves, no war or weapons, no advertising. But it does have a scapegoat: a single individual child, locked in a basement closet, which suffers untold abuse throughout the course of its life. The narrator explains that the abuse of this child is fundamental to sustaining the utopia, and while most of the city’s citizens are content with that knowledge, there are those who walk away from Omelas, unable to accept the utopia’s scandalous foundation. I imagine Peterson’s take on the subject would be something akin to, “You can’t walk away from Omelas because you’ll walk right into another damn Omelas. All cultures are Omelas!” In the hero hierarchy, which prizes the dragonslayers over the slain, not everyone walks away with a life that justifies its innate suffering. And Peterson knows this, arguing the utilitarian reality is better than the naive and idealistic alternatives.

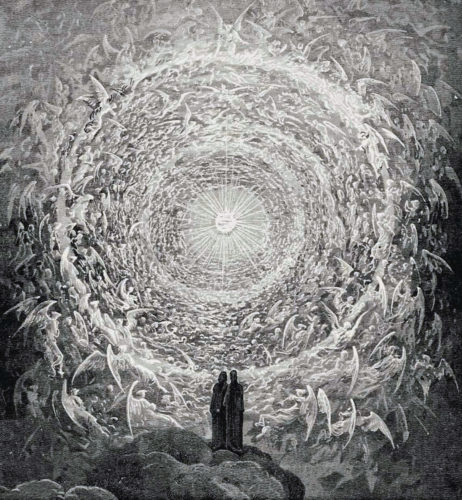

There’s also a remarkable lack of love in Petersonism. It exists, but mainly in the form of an evolutionary psychologist’s love that binds herds and propagates the species. It’s a far cry from Dante’s “love that moves the sun and other stars.” It’s not love, in fact, that moves Peterson’s sun and stars, it’s something completely different. Borrowing the Johannine language, Peterson’s prime mover is the “logos,” which is not necessarily Jesus, but the confluence of reality and speech, the acknowledgement and articulation of the way the world actually exists. The proper articulation of reality is what moves the world forward, says Peterson, and false speech, deception, and censorship threaten to knock the world out of alignment and back into chaos. Which is true in many ways, but in continuing that direction we very quickly find ourselves distracted from the New Testament’s sui generis emphasis on love as expressed in the archetype of a suffering servant.

If the diagnosis is that I haven’t adequately prepared or gone through the training I need to slay the dragons in my life, to paraphrase Westley again from Princess Bride, “somebody’s selling me something.” I’m being cheeky of course. Truthfully, I am afraid I haven’t done Peterson’s thought justice. It’s outlined fully in his Maps of Meaning, which is a very dense 564 page book I haven’t read yet. Peterson has expressed a desire to be as accurate and precise with his words as he can be, and if I haven’t given his worldview a fair shake, that’s certainly on me.

Even though St. Paul and Dr. Peterson may part ways ways on the solution, they agree on the diagnosis, and that’s a rare joy, and one worth noting. For those looking for killer sermon illustrations about original sin, human frailty, and the capability of the average person to do inexplicable evil, look no further.

Still, I hold out hope for a better Omelas, one where weakness and love are not so unwelcome. I think Peterson is right, by the way, that we will always have Omelas, a world of the blessed at the expense of the cursed. Any hope of walking away from Omelas was extinguished with the first bite of that ancient archetypical apple.

But what about an Omelas that looks like this: instead of a hierarchy based on competence or work ethic, we double down on the archetype of the “perfect life” story. Let’s put the perfect people on one side of the hierarchy and the imperfect people on the other. Now, hear me out, I know this sounds crazy, but let’s take all the perfect people– how many do we have, just one? Let’s take the one perfect person that ever existed and put him in the basement closet of Omelas. Or better yet, let’s hang him outside, in public, where everyone can see him, at the entrance of Jerusalem–I mean Omelas–so it’s not hidden and it can’t be ignored. It certainly sounds like the upending of the hierarchy, a world where chaos reigns supreme. But that’s a world where the defeated have a chance, where the weak on the wrong side of the hierarchy can be fully welcomed, and love is the order that moves the sun and other stars.

COMMENTS

10 responses to “Can Jordan Peterson Walk Away from Omelas?”

Leave a Reply

????

Helpful

This is excellent!

Darn it, I was hoping to write the first Jordan Peterson MBird article, working title Jordan B Peterson and the Allure of the Law 😉

But I am glad to see a JBP article here even if I didn’t write it ❤️

That last paragraph took me by surprise and is wonderful. Thanks so much!

Except that there was no government-mandated pronoun use… While Peterson’s charge that reducing ourselves to identify groups is harmful to society, it ignores the way in which marginalized groups have had to band together for mere survival—something dominant group members conveniently overlook. I’ve found that when I scratch the surface of Peterson’s “logos,” it’s full of identity politics of his own and contradictions masked by a calm demeanor. His diagnosis of original sin seems less useful when considering his own fallacies and, perhaps unstated, love for the status quo.

Maggie-I had the same thoughts.

Peterson is great as a Freudian Moses, pointing out with credibility the crisis of our condition. I also think he – maybe without knowing it – rightly unveils the gnostic and pelagian drives behind the newest version of the sexual revolution, and the newest pushes regarding gender. He’s a deeply needed corrective. Well done, Bryan.

Maggie-I had the same thoughts.