Americans just observed Memorial Day, a day most spend watching parades and cooking out, enjoying a day off of work and anticipating the return of summer. You’ll see flags undulating in the breeze on porches and automobiles and hear bands blasting patriotic songs to honor the servicemen and women who lost their lives throughout our history. But if you’re anything like me you don’t know the grisly historical background that provoked the holiday in the first place. Until this past Monday, I had no idea it began as a national grieving for the cataclysmic loss of life and humanity the nation had endured in the Civil War. Every year at this time I watch something pertaining to American military history, and so, the day having come, my wife and I opted for PBS’ 2012 documentary “Death and the Civil War.” We were stunned by this powerful portrayal of how the war radically altered the public consciousness of embodiment and death. Dizzy from the film’s revelations, I recognized in it a mirror held up to our own era, exposing a genealogy of belief which would otherwise remain invisible. If we trace this genealogy, we will find a frightening family resemblance between the treatment of bodies then and now we probably would never have expected.

The Civil War rendered certain theoretical questions grimly tangible in a way none were prepared for. Two such questions are emblematic here: What are smoothbore rifles capable of on a modern battlefield? And what are the reciprocal duties of citizens and the state when it comes to those citizens’ bodies? Sadly, these questions met in the middle in over seven hundred thousand lightning flashes of pain and terror as the chaos the war unleashed forced the federal government to reevaluate their obligation to the resultant corpses. “Death and the Civil War” outlined how our modern federal bureaucracy sprang out of the awareness that the government had failed the governed in turning a blind eye to the practical necessities of handling dead and wounded combatants. Sanitary commissions, ambulance corps, methods of embalming and relocating cadavers, and administrative channels to oversee the registration and identification of millions of mobilized soldiers were all innovations which birthed the infrastructure of the system we recognize today.

Why were we all so unprepared at the war’s beginning, though? Not because the public lived in denial of death. On the contrary, the film made it clear that Americans of the Civil War generation prepared for and understood death in a way contemporary culture simply cannot. Death was a regularly repeating rhythm of life, an end which projected itself forward and reminded them of their limitations as creatures. Both sides shared to a large extent a vision of dying well as the culmination of a life well lived. To live well meant glorifying God in all things. To die well meant holding on to one’s dignity in his final moments, to be surrounded by one’s family and friends, to be attended by a minister, and to have a proper burial.

The war, however, shattered these expectations with a brutality no one could have foreseen as the strategies of Frederick the Great’s or Napoleon’s era collided catastrophically with the technology of the modern industrial age. Columns of troops marched shoulder to shoulder into engagements armed with weaponry more lethal than ever in human history, with vastly improved accuracy, rates of fire, and range. As the documentary made superabundantly clear, “The strategy was ten years behind the technology,” and the unprecedented butchery that followed was a direct result of this shortsightedness.

Forced to deal with a version of death they had never before witnessed, soldiers improvised with the basic forms they had inherited. Men on both sides found surrogates for the good domestic death they had always envisioned: surrounding themselves with gilded images of absent family members, with comrades befriended in the camp and on the battlefield, in makeshift deathbeds with tokens of home nearby. These served as icons of life lived in absentia from true home where peace was unbroken and all was well. These images and tokens communicated home in a way that ministered to the whole person and eased their passing out of this rapidly dehumanizing conflict.

Tragically, this conflict erupted in the first place precisely because the social and economic order of half the nation had been constructed upon the denial of humanity to and the subsequent exploitation of black bodies. And yet the crusade to restore union and defend liberty took no thought to honor the bodies of the fallen in any systematic, intentional manner. I was stunned to discover that the governments of North and South both recognized no responsibility towards the bodies of its soldiers the first years of the war, and the subsequent horror of being left dismembered and exposed like animal carcasses haunted the rank and file. They knew there was no guarantee their remains would return home to their loved ones or that their families would ever learn the manner and location of their passing. The apathy of Union and Confederate governments both was appalling and guaranteed that the home front suffered an unbearable disconnect from the columns of blue and grey maneuvering back and forth over the same contested ground month after month.

The landscape they traversed came to resemble more and more a descent into Hell. The men making up those columns couldn’t escape the miasma of death: storyless corpses littered the roads, the fields, and the backyards of the Confederacy, rendering the American South, in the words of Union quartermaster Edmund Burke Whitman, “one vast charnel house of the dead.” The ghastly magnitude of lives hideously extinguished, unparalleled in the nation’s history, (un)naturally gave rise to the reduction of casualties to statistics in reports and newspapers. The barbarity of the fighting matched the desecration of these image bearers’ bodies in the aftermath of battle as they were left unburied and unidentified. Hundreds of thousands of blood-drenched agonies and prayers went unnamed as men and boys expired where they fell, robbed of the dignity rightly due them.

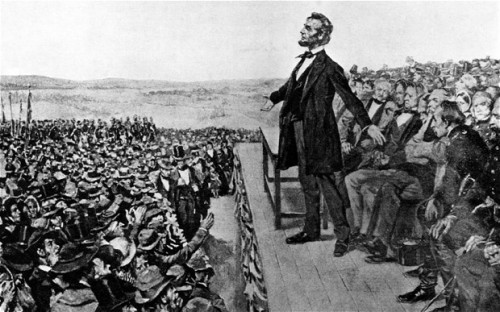

The Union began to heed its responsibility to its civic body at last in the dedication of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery, the occasion of Lincoln’s famous Gettysburg address. Lincoln’s elegy was more than a commemoration of the sacrifices made on this battlefield: it was nothing less than a civil liturgy mining for national redemption as the thousands of dead were interred at last. While genuine catharsis and a measure of healing was provided through the symbolic action of properly burying our dead, casualties only mounted to horrifying new levels over the next two years. The bodies of fallen American soldiers were politicized to construct the narrative shape of our modern national identity. A civil religion was born in which the bodies of its citizens were harnessed as capital. And the depersonalization that began with the unprecedented death-dealing technologies of the war years contaminated the home front as industrialization and its attendant consumerism became the new norm.

So where are we now, we who look forward to the three day weekend Memorial Day provides us? We are the inheritors and inhabitants of that civil religion and our bodies, we’ve been taught, matter nearly as little as then. We now sit at home surrounded by icons of elsewhere, longing to be everywhere and nowhere all at once. We find ourselves diametrically opposite the Civil War generation, for we have no preparation for dying well nor for living well. We shun death’s denial of our autonomy and run headlong as far away as we can whenever we catch even a whiff of its excremental aroma. And we have no conception of the good life because we have been conditioned to capitalize on a merely formal vision of freedom as amoral choice between limitless options.

Interwoven with this is a secularized Gnostic strain that has crept into our modern narrative of freedom and selfhood and sabotaged the value of our physical constitution. On this view, the body is a mere husk encasing the “true” self, or, at best, an interface between that “self” and the outer world of objects and “other minds” (note the identification of self with mind in that phrase). We might be fooled into thinking our preoccupation with bodies is evidence we cherish them more than our inhibited ancestors, but our obsession is only with the instrumental value our bodies provide us. Not unlike the federal government of 1861, bodies are useful only for accomplishing certain things, usually for asserting the value of the self. I wonder if this enthronement of the ego reduces the body to a mere playground of identity construction, individually arbitrated with no attention to tradition or community and unlimited by the constraints of nature. The distinctions of embodiment are regularly explained away as social constructs to reinforce bourgeois conformity and cordon off the other, almost never as positive parameters for understanding and pursuing the good life. Feelings and identity politics are the only sure guides to this body-irrelevant way of life.

What are the consequences of these beliefs? Physician-assisted suicide is viewed by the majority of Americans as a liberating exercise of freedom when life becomes unattractive. Reproductive technology uncomfortably blurs the line between offspring and product. Sexting, pornography, and hookup culture make commodities of sex by diminishing the value of physical intimacy and packaging our bodies as consumer goods. Boys, men, and the fellows everywhere in-between are subjected to shame for distinguishing male characteristics while women find their fertility devalued by the medical profession and recast as irrelevant. And an epidemic of obesity has seized enormous swathes of the American public in a living rigor mortis, shrinking their worlds to the enslaving powers of the entertainment-industrial complex.

In all of these cases, when we no longer see ourselves as the subjects in and of these actions, when our bodies are no longer viewed as intrinsic to human flourishing, we distort and degrade our embodiment. This may sound like prudery to some, but isn’t: it’s the insistence that our bodies, just as much as our rational and emotional faculties, are the basis of our bearing the image of God, for our bodies are the locations of worshipful response to God’s action in the world, the world we participate in only in and through this matter which, in conjunction with the soul, constitutes our being as humans. Faith, and it with it authentic human existence, is made concrete in our bodily existence.

In all of these cases, when we no longer see ourselves as the subjects in and of these actions, when our bodies are no longer viewed as intrinsic to human flourishing, we distort and degrade our embodiment. This may sound like prudery to some, but isn’t: it’s the insistence that our bodies, just as much as our rational and emotional faculties, are the basis of our bearing the image of God, for our bodies are the locations of worshipful response to God’s action in the world, the world we participate in only in and through this matter which, in conjunction with the soul, constitutes our being as humans. Faith, and it with it authentic human existence, is made concrete in our bodily existence.

On Pentecost (the day before Memorial Day, take note!) the church was anointed to make Christ’s rule visible to a languishing world, to bear witness to a better way to be human, a way made possible by the one authentic human being in history, Jesus Christ. But the integrity of Christian witness, I’d wager, will depend on our owning up to vain pretensions of righteousness and control and repenting of the compromises and illusions of which we are all guilty–which, in this case, includes identifying the image of God with the soul and not our possession of bodies as representative media. Simply harping against society’s ills will be ineffective (if not futile), as our inconsistencies will invariably drown out our criticisms.

Just as with the Civil War, evangelical strategy typically lags behind the technology, and it has little-to-no hope of catching up so long as our ethics are cut from the same voluntaristic cloth as the dehumanizing practices we protest. In fact, any “alternative” vision that begins with isolated, storyless selves pursuing consumer impulses will be as death-dealing as the one it opposes. The endlessly creative gospel of total helplessness remains the only place to start and the only place to keep returning to. As Memorial Day fades from view, may we all take to heart the image that the past reflects back and own its criticism, glorifying the Redeemer with our bodies and embracing the restoration he has promised is already finished and awaiting us. For we are not our own–we were bought with a price.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=goFFVg0T4e0

COMMENTS

One response to “The Civil War, Memorial Day, and the Politics of Embodiment”

Leave a Reply

This is really powerful. So well written. No prudery here. ’embracing the restoration’. You think about that when you are at the end of the runway like I am.