Many things separate us in the twenty-first century from our ancestors. Some of them are obvious — cars, cell phones, flush toilets — and others less keenly understood, but nevertheless intuited. We all sense a vast gulf between the present and half a millennium ago, but in what does it primarily consist?

Philosopher Charles Taylor gathers these more intangible differences under the rubric of “the porous self” versus “the buffered self.” To summarize all too briefly, the belief that what distinguishes modernity from the past is the loss of certain beliefs and the adoption of new and better beliefs is, itself, an invention of modernity. That is, while some beliefs about the world and ourselves have more or less been jettisoned, what best characterizes the difference between us is not the inventory of beliefs we have but our orientation to the world.

Our ancestors negotiated the world with porous selves, open to the influence of forces outside themselves and largely at their mercy. Whether demons, ghosts, the stars, the humors, or any other such nonhuman entity, the human self was fundamentally receptive: no boundary protected the self from the outside coming in and affecting it.

The modern buffered self is closed off, believing itself stable and stalwart against the encroachment of what is outside that self. That buffer allows me to distance my feelings and urges from reality in its most fundamental sense. Not that my feelings and urges aren’t real, but that they come and go, are subject to flux, are based in things that can be sanded down with therapy and medication, or otherwise fixed. What is most real just is — pacifically so, not subject to contingency or instability. Nothing “out there” can shake or break the foundation of reality’s “inside.”

The buffer that keeps the nonhuman out and separates inside and outside, real and the mutable, promises a kind of freedom, one we in modernity simply assume, but the cost is what Taylor calls “disembedding”: the comprehensive severing of human life from the webs of relationality which once defined our existence. At best, such relationality is optional, and at worst, obsolete and crude.

We have become unmoored from the wider, deeper world which is supplied and fallen back upon our own resources and self-discipline to see our way through. This is celebrated as humanity having “come of age,” but our experience of this buffered consciousness routinely comes up short of that ideal. The options available to me feel drastically dried up. Life feels evacuated of possibilities, less like an open road and more like a revolving door. We all know the result quite well: ostensible maturity but an unshakeable sense of, “Is this it?”

This makes nostalgia for the porous past sensible, although perhaps romanticized. An enchanted world, after all, is a dangerous one. The powers that make vaster, stranger possibilities available are by nature disruptive and often not amenable to our agendas.

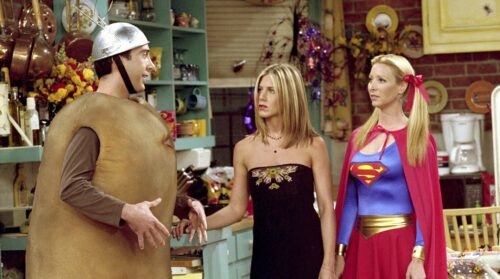

But what if there was a day in which our buffers could undergo physical therapy so that we could relearn the muscle memory of porousness? A day in which we could play dress-up with other selves we could have been? Or fear to become? What if that day permitted us to try on different options which ordinarily were closed off to us?

Because for one day the net of presuppositions loosens and drops away entirely. The medieval practice of Carnival survives in Halloween, where the fool can be king for a day, where ruler and ruled can exchange stations and the vice grip of what is possible and what is allowed is relaxed. Carnival back then relaxed the strictures governing people’s lives for one day so as to re-consecrate the norm when it was all over. The pressures exerting themselves within that world were discharged and ridiculed before returning to them the following day.

Halloween today, however, can subvert those pressures and tensions persistently bubbling to the surface of our collective existence, premised as many of them are on the arbitrary laws of the Modern Moral Order, alienating us from ourselves, our fellows, our planet, from the unseen world of spirit we are often told is preposterous or irrelevant.

Halloween places an un-ignorable question mark against the ironclad presuppositions of our age. If all these things are so, and are making us better than our species has ever been, then why do so many of us clamor for this release? If we are all better off jettisoning the childishness of spirit and make-believe, why is there such a hunger for the imaginative possibilities unique to this day?

Because the rest of the year isn’t like this, and we know it. This is why, in spite of our pathological hatred of Monday mornings and the angst which permeates the work week, we eventually deactivate the snooze feature on our alarms and somnambulate through our schedule. The net is tight, and our vision is constrained by its mesh. We know what we’re “supposed to do.” There is only us and what we might make of ourselves. And more people are awakening to the hopelessness of such a picture.

The risk of openness feels mitigated on this day, a recess from the constriction and sterility of the buffering that structures every other day. The payoff? That for one day, even I can be a hero. In spite of my routine foibles and the failures of which I am most ashamed, I can nevertheless take up that mantle and be something more than the fraud I fear I am, day in and day out.

For one day I can admit my baser urges and be a villain, confident that my costume does not confirm what I am in the uttermost depths of my being and therefore will not expose to the world the profoundest truth of what I am beneath the façade I present.

For one day I can masquerade as one of the beings that haunt our world, which terrorized our ancestors and now more invisibly influence us, confident of their defeat by the cross of Christ. I can join in his making a spectacle of the powers and principalities by gallivanting about as though I were one of them.

The customary rules of life in this age are locked away for one day, allowing me to give voice to normally forbidden things. If I am not in control; if the world’s magic is real, is more pervasive than I allow myself to believe the rest of the year; then life isn’t as devoid of possibility as I feel it is each day — there are more paths and more entities and sources of wisdom than I am told there are every other day. Yes, the danger exists that what is out there is stronger and smarter than I am. But that also means that adventure is possible.

Halloween is the day we train for life in this strange world of ours rather than suppressing that strangeness. Halloween and the Spooky Season may not be enough to overturn the entire Great Disembedding, but perhaps our horizons can be broadened a little bit more through them. Perhaps we can awaken to more possibilities than we’ve allowed ourselves to believe. That the past doesn’t absolutely determine the future. That the weekly grind is not the truest story of our lives but is the setting for all manner of strange and spooky magnificence to enter into. That perhaps maybe, over time, we can nudge ourselves — or be nudged? — out of that buffered net and into the wild world of the real.

After all, I already am painfully aware of how I am not in control; I’ll take the solace that the world is massively more than what I make it.

COMMENTS

2 responses to “Halloween: A Recess for the Buffered Self”

Leave a Reply

[…] take on Christianity and Halloween, see any of Ian Olson’s annual reflections (here, here, here, or […]

[…] Halloween: A Recess for the Buffered Self – Mockingbird — Read on mbird.com/philosophy/halloween-a-recess-for-the-buffered-self/ […]