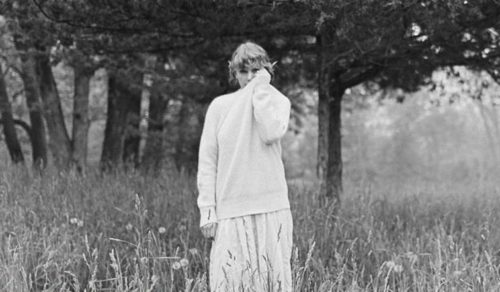

Last Thursday, Taylor Swift announced the surprise release of her eighth studio album, folklore, to be dropped that night at midnight. The album is made up of 16 songs Swift created in quarantine with the help of Aaron Dessner of The National, alongside Jack Antonoff, Bon Iver, and others. Naturally, my friends and I stayed up to listen and got through almost the whole album before we drifted off — oh, and curled up in balls on the floor, emotionally lacerated.

Last Thursday, Taylor Swift announced the surprise release of her eighth studio album, folklore, to be dropped that night at midnight. The album is made up of 16 songs Swift created in quarantine with the help of Aaron Dessner of The National, alongside Jack Antonoff, Bon Iver, and others. Naturally, my friends and I stayed up to listen and got through almost the whole album before we drifted off — oh, and curled up in balls on the floor, emotionally lacerated.

If you haven’t yet given it a listen, you should, but be warned: It may hurt you. As one twitter user noted, “Taylor Swift saw us not social distancing so she wrote an album so beautifully emotionally crippling that we’d draw the blackout curtains, light a candle, wrap ourselves in a cardigan and never get off the couch again,” a description so apt, Swift herself retweeted it.

This album shows a major shift in her approach to songwriting, as she found herself, in her words, “not only writing my own stories, but also writing about or from the perspective of people I’ve never met, people I’ve known, or those I wish I hadn’t. … In isolation my imagination has run wild and this album is the result.” Her decision to write from other people’s perspectives and the indie/soft rock/alternative sound of the album mark a definitive jolt away from the last near-decade of high-gloss pop and popularly scrutinized autobiographical lyrics. This album certainly has a mature quality, displaying a Swift unafraid to stare unflinchingly at gaping wounds and drop an f-bomb along the way. The songs tell tales she gleaned from “fantasy, history, and imagination.” Sometimes it’s unclear if she’s telling her own story or someone else’s, if it’s fact or fiction, if the story is played down or embellished — and that’s totally the point. They’re folktales: rumors, fables, gossip, stories passed down and maybe altered over time.

In a Vulture album review, Jill Gutowitz points out that, for the first time, all her song titles are stylized in lower-case letters. She theorizes:

A lowercase girl texts and posts in lowercase letters so as to appear relaxed; we are the antithesis of thirst, having been terrorized by love lost so many times that we can no longer bear to even seem like we care enough to text you with proper capitalization … A lowercase girl album, like a lowercase girl, signifies ambivalence, nonchalance, and unfortunately, a Trojan horse of emotional terrorism.

Case in point: the tease of upbeat chords and lyrics in the album’s opening song, “the 1,” which quickly devolve into nonchalant, casual confessions of broken dreams and musings of what could’ve been. Though Swift starts off by telling us that “I’m doing good / I’m on some new s**t,” she later sings in her soothing, sweet voice, “And if my wishes came true / It would’ve been you … it would’ve been fun / If you would’ve been the 1.” The tone may be soothing, but the lyrics are not, especially when she coos, “And it’s another day waking up alone.” I have to agree with Gutowitz’s assessment that it is only the beginning of a “16-piece psychological attack intended to break every last person who hasn’t yet been broken by quarantine.”

folklore is melancholic, ethereal, and nostalgic. Bottled-up emotions bubble up and burst at every seam. Amid layers of austere piano, saxophone, cello, and even the occasional harmonica, it whispers of mad women, romanticizes toxic relationships, writhes in the agony of discovering an unfaithful partner, and bares teeth and scars. “invisible string” may well be the only truly hopeful-sounding song on the album. In short: folklore is heartbreaking, and it is beautiful.

folklore is melancholic, ethereal, and nostalgic. Bottled-up emotions bubble up and burst at every seam. Amid layers of austere piano, saxophone, cello, and even the occasional harmonica, it whispers of mad women, romanticizes toxic relationships, writhes in the agony of discovering an unfaithful partner, and bares teeth and scars. “invisible string” may well be the only truly hopeful-sounding song on the album. In short: folklore is heartbreaking, and it is beautiful.

But more than anything else, this album sounds to me like a quiet surrender, a painful and slow process of finally coming down on one’s knees and begging for spiritual renewal and redemption. As Swift sings in “mirrorball”: “I’m still on that tight rope … I’m still a believer but I don’t know why / I’ve never been a natural, all I do is try, try, try.” Although on the surface the song is about a girl (who may or may not be Swift herself) trying — for something like the thousandth time — to earn and retain the affection of her lover, it also has a spiritual undertone. There is ample reason to understand “believer” to mean a believer in God, especially in light of the spiritual grappling she revealed on her last album, Lover. “Desperate people find faith,” she confides, “so now I pray to Jesus, too.”

It seems that, on folklore, she is “still a believer,” but she and all those she writes about are beaten down from trying — trying to earn the love of other people and of God. There is a palpable fragility in Swift’s voice. In “illicit affairs,” she sings, “and you wanna scream / Don’t call me ‘kid,’ don’t call me ‘baby’ / Look at this godforsaken mess that you made me.” But even then, her voice is soft, almost muffled or stifled; she wants to yell in anger, but she can’t. Instead, she barely sings above a whisper. Swift sounds tired, like she’s been emotionally wrung out.

More than her sad songs from previous albums (with seven other albums, there are plenty to choose from), the ones on this track affect me more deeply, and I think I know why. On this album, more than on her others, there is a sense of communal pain. These aren’t just Swift’s stories of disfiguring lies and searing scars — they are many people’s. And because there is no telling for sure which stories and characters are made up and which are true, any of these stories could be yours or mine.

That, in addition to the fact that, on at least one occasion, Swift tells the same calamitous story from three different perspectives, revealing tragedy’s wide girth: heartbreak spares no one. I buy into the theory that “illicit affairs,” “betty,” and “cardigan” represent what Swift referred to in a YouTube comment as “The Teenage Love Triangle.” As Gutowitz explains, “All three songs are written from each person in the love triangle’s POV: ‘illicit affairs’ being from the POV of the girl who the boy cheated with, ‘betty’ being from the POV of the boy, and ‘cardigan’ being from the POV of Betty.”

Every one of these songs is haunting, tear-jerking, and regretful in its own way. The cheated-on girl in “cardigan” is left rejected and “bleeding,” and the boy in “betty” who did the cheating laments that “the worst thing I ever did / was what I did to you.” He anxiously ponders: “If I showed up at your party / Would you have me? Would you love me?” It’s not entirely clear if he means the girl he cheated on or the girl he cheated with, and certainly, the ambiguity is purposeful. The emotional wreckage continues with the girl in “illicit affairs”: “And you know damn well / For you I would ruin myself / A million little times.” All three are “bleeding” and in ruins, wondering if they will ever be loved.

Both the characters Swift sings about and we listeners are left reeling at the conclusion of folklore, weighed down by sin and tragedy and tired of standing on the “tight rope” trying. Swift beckons us in with a false sense of playfulness, and then asks us to “look at this godforsaken mess.” She brings us to the mess — or, more accurately, reveals the one we’re already in — but she doesn’t show us a way out. In “my tears ricochet,” she further divulges that she actually can’t lend a hand even if she wanted to: “I didn’t have it in myself to go with grace.” She can’t heal the wounds and clean up the mess. She already tried a thousand times and failed. Sound familiar?

Swift plucks at the heartstrings of our universal human condition. We can “try try try” to get ourselves out of the “godforsaken mess” and earn God’s love, but we can’t succeed. But God does not leave us forsaken in our mess — He places our mess on His own shoulders and offers us the way out: He does have it in Himself to “go with grace,” and He gives us the redemption we all need. Intentional on Swift’s end or not, folklore reminds us that we can come down off the tight rope and quit our act — God sees the mess, enters into it, and loves us anyway.

Listen here on Spotify.

COMMENTS

2 responses to “The Beautiful, Godforsaken Mess of Taylor Swift’s folklore”

Leave a Reply

You know I clicked on this right away…! Excellent write-up, Sarah. I love the observation about the lowercase letters. I think it was “reputation” when Swift kept using the word “chill” — likewise indicating the exact opposite. Haha. This album is such a gift. She has always been a brilliant songwriter but the pomp & circumstance (& vengeance!) of every other release would usually detract from that

[…] Swift’s spiritual reckonings and undertones in her lyrics for some time now (see my reviews on folklore and evermore), and Midnights has only made me go further down this […]