Edvard Munch, The Girls on the Bridge, 1901, oil on canvas, 136 cm x 125 cm, National Gallery, Oslo. From 1899-1927, Munch painted various versions of this theme.

“Girls on the Bridge” by Derek Mahon

–Pykene na Brukken, Munch, 1900

Audible trout,

Notional midges. Beds,

Lamplight and crisp linen wait

In the house there for the sedate

Limbs and averted heads

Of the girls out

Late on the bridge.

The dusty road that slopes

Past is perhaps the high road south,

A symbol of world-wondering youth,

Of adolescent hopes

And privileges;

But stops to find

The girls content to gaze

At the unplumbed, reflective lake,

Their plangent conversational quack

Expressive of calm days

And peace of mind.

Grave daughters

Of time, you lightly toss

Your hair as the long shadows grow

And night begins to fall. Although

Your laughter calls across

The dark waters,

A ghastly sun

Watches in pale dismay.

Oh, you may laugh, being as you are

Fair sisters of the evening star,

But wait–if not today

A day will dawn

When the bad dreams

You scarcely know will scatter

The punctual increment of your lives.

The road resumes, and where it curves,

A mile from where you chatter,

Somebody screams.

The girls are dead,

The house and pond have gone.

Steel bridge and concrete highway gleam

And sing in the arctic dark; the scream

We started at is grown

The serenade

Of an insane

And monstrous age. We live

These days as on a different planet,

One without trout or midges on it,

Under the arc-lights of

A mineral heaven;

And we have come,

Despite ourselves, to no

True notion of our proper work,

But wander in the dazzling dark

Amid the drifting snow

Dreaming of some

Lost evening when

Our grandmothers, if grand

Mothers we had, stood at the edge

Of womanhood on a country bridge

And gazed at a still pond

And knew no pain.

It was the thick, choking smoke of the wind-driven California wildfire that shocked me the most. Fleeing my home after waiting too long to leave, I drove through a sickly surreal otherworld of yellow darkness, worse than any nightmare sequence imagined by David Lynch. Afraid that tree branches would fall as the wind roared with fury, I struggled to see other cars around me, so I turned on my hazard lights — only to make a wrong turn on one of only two avenues of escape that remained. Careening around the corner, I saw that the fire had crossed the road and was engulfing the tree branches overhead, which blazed red through the yellow blanket of smoke. I felt the heat and embers on the car as I quickly drove through the flaming archway. And then I saw it: the bright blue of the midday sky on the other side. Every possible metaphor and analogy regarding weathering the storm of suffering randomly sprang to mind as I tried to calm my shaking hands to steer to safety.

The view from my window.

Stories like this became standard fare in November 2024 and January 2025, as the Santa Ana winds whipped across Southern California, gathering enough gale force to fuel the fires from the coastal mountains to the edge of the sea. In Slouching Towards Bethlehem, Joan Didion famously captured and conveyed the overwhelming danger of the Santa Ana winds in the literal and mental landscape of Los Angeles:

It is hard for people who have not lived in Los Angeles to realize how radically the Santa Ana figures in the local imagination. The city burning is Los Angeles’s deepest image of itself; Nathanael West perceived that, in The Day of the Locust; and at the time of the 1965 Watts riots what struck the imagination most indelibly were the fires. For days one could drive the Harbor Freeway and see the city on fire, just as we had always known it would be in the end. Los Angeles weather is the weather of catastrophe, of apocalypse, and, just as the reliably long and bitter winters of New England determine the way life is lived there, so the violence and the unpredictability of the Santa Ana affect the entire quality of life in Los Angeles, accentuate its impermanence, its unreliability. The wind shows us how close to the edge we are. (220-221)

Such impermanence can embody both seductive attraction and violent repulsion, as represented in Raymond Chandler’s noir story “Red Wind,” and most of the region has been living on edge from Chandler’s time until today — until the annual rains soothe some of the anxiety away.

In early November 2024, I began writing an analysis of the poem featured above, but when the Mountain Fire erupted, those plans were put on hold. In early January, I approached the poem again, but then sheets of flame poured down the hillsides of Pacific Palisades. Various lines from the poem — “we live these days as on a different planet” — accrued new and sinister connotations as I dealt with the devastating aftermath of the California firestorms. The only aid came when I remembered that once there was a time when William Faulkner decided to write for himself, even if no one else read his work, even if it never got published, and that was his mindset when he sat down to write The Sound and the Fury. And so I finally returned to writing about the peculiar genre of ekphrasis — otherwise known as poems about paintings — fully aware that this genre may not appeal to a large audience, fully aware that “poetry makes nothing happen,” as W. H. Auden once wrote, and yet … and yet, stick with me through this meditative, labyrinthine essay, and we’ll see if Auden and I come to different conclusions by the end.

In the poem featured above, Derek Mahon exhibits a technical virtuosity of extraordinary balance as he explores themes of nostalgia and ecological dystopia, centered on Edvard Munch’s painting Girls on a Bridge (c. 1899, 1901), where three girls gaze into the water, which is dominated by the reflection of a massive tree in the background — likely a linden tree, though it also resembles a weeping willow tree. This image is mirrored in the structure of the stanzas, which emulates the rounded shape of the tree and its reflection in the water. The mirroring rhyme scheme of abccba partners with a nearly symmetrical syllabic count to underscore the heavily reflective emphasis of the poem, as the viewer joins in plumbing the depths of an endless echo of reflections into the past, present, and future.

In the first stanza, the speaker surprisingly evokes imaginary aspects of the painting as he seeks to bring it to life in a third-person narrative overview, opening with fragmented phrases and images of the natural environment, as he highlights the sense of sound rather than sight to indicate the croaks of “audible trout.” Drawing upon a longstanding tradition in his mention of “notional midges” (imaginary gnats), the speaker ironically alludes to “notional ekphrasis,” which is a description of an imaginary work of art rather than an actual one, as typified in poems like Robert Browning’s “My Last Duchess” and Percy Shelley’s “Ozymandias,” and which foreshadows an important moment later in the poem. The first stanza also summons a warm vision of Victorian or Edwardian domesticity that beckons the girls to safety, even as the alliterative sound effects and internal rhymes offer a lilting appeal: “Lamplight and crisp linen wait/ In the house there for the sedate/ Limbs and averted heads/ Of the girls out/ Late on the bridge.”

This capacity for imaginative revelation will expand dramatically later in the poem, but first the speaker returns to regular conventions as he describes the road that fades into the receding perspective at the right of the painting, employing timeworn tropes of hopeful innocence and youthful exploration. Capturing a carefree moment in time that represents the peace and prosperity of the late nineteenth century, the speaker describes the girls a bit like plaintive ducks in a shallow conversation, which contrasts with the depth of “the unplumbed, reflective lake,” as “their plangent conversational quack” is “expressive of calm days and peace of mind.”

With the word “grave” — and all its connotations of seriousness, gravitas, and death — a shift in tone occurs, similar to the volta in sonnets, as the imagery suddenly descends into darkness. As the painting figuratively springs to life in a narrative succession of actions, the girls toss their hair as “the long shadows grow,” while “a ghastly [personified] sun/ watches in pale dismay.” The three girls, “fair sisters of the evening star” (Venus/love), are also “daughters of time,” and the tide of time is about to turn into the twentieth century, when the great European nations will reach their zenith and explode into the conflagration of two world wars. The apostrophic invocation of the “grave daughters” and the sudden use of the second person suggests a second speaker here, a new narrative voice that sounds classical, archaic, and elegant, but also conveys an eerie cadence with ominous overtones. The present tense direct address of stanzas 4–6 indicates an “eternal now” that contrasts with the past Victorian/Edwardian era of stanzas 1–3 and the future vision given in stanzas 7–10.

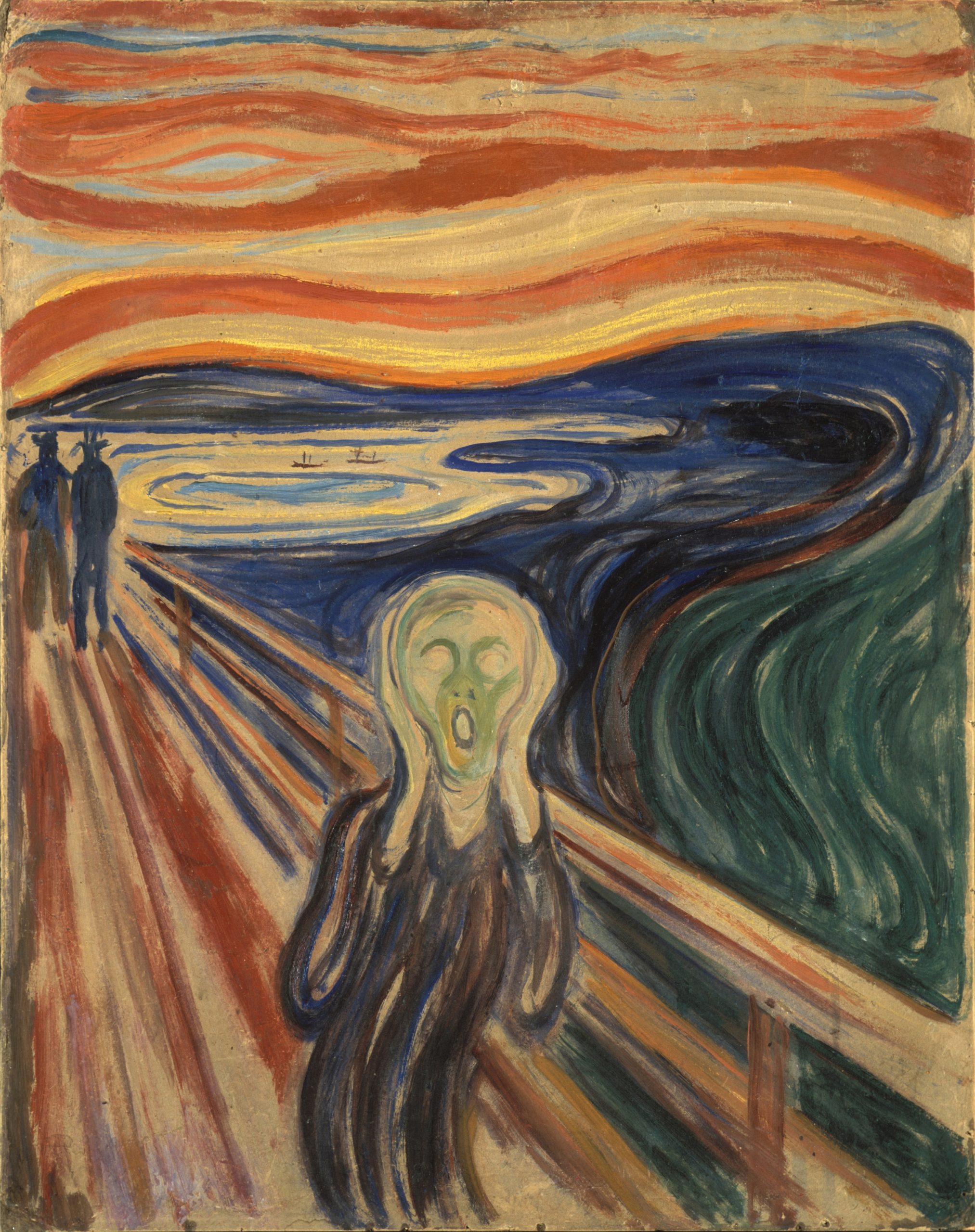

Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1910, tempera on board, 66 x 83 cm, The Munch Museum, Oslo. Munch painted various versions of this image, based on his initial 1893 painting. In this version, the background figures look animalistic or demonic, whereas in the background of the 1893 painting, the figures look more humanoid, possibly clerical.

In the sixth stanza, the road is no longer a symbol of hope and progress, but rather a sinister development with an unexpected turn of events: “The road resumes, and where it curves,/ A mile from where you chatter,/ Somebody screams.” With a sudden shock of revelation, the reader realizes that the speaker is alluding to the most famous painting by Edvard Munch — The Scream (1893, 1910) — where the swirling colors and distorted features of the figure on the bridge have come to encapsulate the psychological anxiety and trauma of the twentieth century. Foregrounding the power of the written word to spark a visionary journey beyond the current painting, the poet takes us down the road by bridging into another painting in our imaginations, one that offers a stark contrast but also reflects its paired twin in an uncanny fashion. This is an elaborate variation on notional ekphrasis because we can see the existing second painting in our mind’s eye, even though our attention was initially focused on another painting. The two paintings are like mirrors held up to each other — cracked by the cataclysm of the new century — offering a mise en abyme of endless reflections and refractions.[1] There may be no escape, in other words, from these suffocating echoes of innocence and experience, as they both exist along the same looping, circuitous road of nostalgia. Yet the power of the written word to spark such a profound imaginative vision nevertheless suggests the potential for redemption.

Replete with harsh high vowel sounds and crisp cutting consonants, the next two stanzas are the finest in the poem, with another volta of revolutionary change, showing us a radically changed landscape, and reminding us that we are no longer shocked by the horror of the painting, the trauma of the twentieth century, or the devastation of industrialism: “Steel bridge and concrete highway gleam/ And sing in the arctic dark; the scream/ We started at is grown/ The serenade/ Of an insane/ And monstrous age.” The painting itself has been relegated to ubiquitous parody and postmodern pastiche, replicated in kitschy fashion across the pop culture landscape — from Home Alone to emojis — an ironic melody for Expressionism and the complex emotions it sought to convey in response to the anomie and alienation of modernity.

Next, the poem flashes forward into the future, but the length of time is unclear, and the narrative voice changes once more to adopt an inclusively communal, first-person plural narration, but with a ricorso — a voice that sounds closer in spirit to the first three stanzas than the invocatory middle ones. This speaker presents a post-apocalyptic voice, perhaps coming to us from beyond the twenty-first century, where species have gone extinct and particulate pollution fills the sky — lines that haunted me during the recent wildfires: “We live these days as on a different planet,/ One without trout or midges on it,/ Under the arc-lights of/ A mineral heaven.” Significantly, Munch’s 1893 painting was first exhibited under the German title, The Scream of Nature (Der Schrei der Natur), and Munch even inscribed a poem on the frame of his 1895 pastel version, which detailed the visionary moment that inspired the iconic image:

I was walking along the road with two friends

The Sun was setting – the Sky turned blood-red.

And I felt a wave of Sadness – I paused

tired to Death – Above the blue-black

Fjord and City Blood and Flaming tongues hoveredMy friends walked on – I stayed

behind – quaking with Angst – I

felt the great Scream in Nature (via Ahn)

This apocalyptic moment, with its reconfigured pentecostal imagery, resonates with the recent firestorms and reminds me of Didion’s dark description of a fiery Los Angeles, while the frame’s ekphrastic intermingling of the verbal and visual arts here demonstrates their profound synesthetic interdependence rather than any sort of rivalry between the two modes of representation.

Expanding upon the themes of nature’s dismay, the melancholy voice of nostalgia then concludes Mahon’s poem, emphasized with the gentle thud of alliteration, describing a people with “no true notion of proper work,” who “wander in the dazzling dark” and “drifting snow,” dreaming of a lost era of innocent grandmothers, who stood in a liminal space of suspension on a bridge between the Victorian and modern world.[2] It’s a poignant poem, though I’m reminded of Woody Allen’s film Midnight in Paris (2011), which showcases the false and futile nature of nostalgia, as every era is nostalgic for ones that came before. The contemporary literary hero in the film is nostalgic for the Fitzgerald/Hemingway heyday of Paris in the 1920s — the Lost Generation — but those literary giants are nostalgic for the Belle Epoque, and the Belle Epoque artists are nostalgic for the Renaissance, and so on, ad nauseum. I’m nostalgic, for instance, for the relative peace and prosperity of the 1990s, much like my father is nostalgic for the pre-Vietnam innocence of the 1950s — but no age is entirely peaceful or prosperous or free of problems, and the 1950s are a prime example of that conundrum. And beneath the shiny veneer of the serene 1990s lurks a memory of Balkan horrors. Like the ouroboros with its tail in its mouth, or the Yeatsian and Viconian cycles of history, this looping circuit of nostalgia is interminable and inescapable — unless we can imagine something entirely new, something healed, and something whole.[3]

***

Like Munch, who painted numerous versions of The Scream and Girls on a Bridge, so Mahon often revised his poetry, and this ekphrastic poem is no exception, drawing attention to our inability to privilege any one single version as the most authoritative (Harrison 69). In one version of the poem, Mahon included the epigraph, “Pykene na Brukken, Munch, 1900,” but in a later edition, he changed the date to 1901, likely pointing us to a specific version of the painting or to revised scholarship regarding the painting’s date (Pearsall 245–246). Even more astonishingly, he deleted the final four stanzas of the poem, which arguably contain the finest sound and imagery, and instead concluded with “somebody screams” — perhaps to emphasize the threshold shock of imagining the second painting (Harrison 69–70). In another twist, the epigraph itself is a peculiar wordplay because it revises the title of Munch’s painting, which is Pikene på Broen (“Girls on the Bridge”), sometimes titled Pikene på Bryggen (“Girls on the Pier”). Instead, Mahon’s epigraph roughly translates to “the boys (are) now broken,” which helps explain the fragmented, tripartite voices in the poem — the grandchildren who are reflecting on a previous generation’s placidity from the perspective of the twentieth century and beyond.[4] The timeframe of the turn of the twentieth century highlights the generation of boys who were indeed broken by the catastrophe of World War One; the bridge of time is also fractured and no longer traversable, and the two paintings held up to each other are like broken mirrors that refract their splinters into endless irreparability.

The revised poem calls into question the earlier version’s progression, while the Enlightenment ideal of inevitable progress is itself called into question by the anomie of modernity, as represented in The Scream — and is further undermined by the slaughter of twentieth-century warfare as well as by the acquisitive frenzy of capitalism. Max Weber’s famous definition of modernity as the “disenchantment of the world” underscores the significance of science in diminishing humanity’s enchantment with the universe by removing nature’s supernatural aura, thereby transforming nature into raw material solely to be exploited for technological use and development. In the face of this devaluation of the supernatural, can poetry possibly reinstate the sacrificial generosity of art as an aspect of devotion, as a means of restoring intimacy between the human and the divine? Maybe, but let’s first weigh questions of generosity surrounding environmental stewardship, as these issues of nostalgia and ecology coalesced and came to life in the aftermath of the California wildfires.

To put all of this into perspective, consider the 2017 Thomas Fire that swept through Ventura County, fueled by gale-force winds, which was the largest wildfire in the history of California at the time. Eight years later, the Thomas Fire is the ninth largest wildfire in the history of the state. Santa Ana winds have always been a part of the regional ecosystem of Southern California, but the increasing severity of fires in the wildland-urban interface is hard to deny. Debating the finer points and nuances of climate issues unfortunately misses the point and sadly delays changes that could help heal the damage, particularly when Christians are called to be benevolent stewards of the glorious creation God has granted us. Even someone as dour as John Calvin encouraged Christians to go outside and enjoy the natural world, where human depravity is thrown into sharp relief against the backdrop of God’s grandeur. In “Tintern Abbey,” William Wordsworth describes a similar moment when he hears the “burthen of the mystery” and the “still sad music of humanity” playing in the background of the grand orchestra of the natural world’s beauty (lines 39, 93).

To put all of this into perspective, consider the 2017 Thomas Fire that swept through Ventura County, fueled by gale-force winds, which was the largest wildfire in the history of California at the time. Eight years later, the Thomas Fire is the ninth largest wildfire in the history of the state. Santa Ana winds have always been a part of the regional ecosystem of Southern California, but the increasing severity of fires in the wildland-urban interface is hard to deny. Debating the finer points and nuances of climate issues unfortunately misses the point and sadly delays changes that could help heal the damage, particularly when Christians are called to be benevolent stewards of the glorious creation God has granted us. Even someone as dour as John Calvin encouraged Christians to go outside and enjoy the natural world, where human depravity is thrown into sharp relief against the backdrop of God’s grandeur. In “Tintern Abbey,” William Wordsworth describes a similar moment when he hears the “burthen of the mystery” and the “still sad music of humanity” playing in the background of the grand orchestra of the natural world’s beauty (lines 39, 93).

Such complexities regarding human interaction with nature are on full display when considering sustainable groundwater management in the face of the depletion of the basins and aquifers of California’s agricultural regions. Tensions have proliferated as the state seeks to navigate the allocation of farmers’ water rights in tandem with local groundwater agencies entrusted with the sustainable management of the basins. Closely related to the question of water management is the question of housing development, particularly at a time when California paradoxically needs less development in the wake of wildfires, but also needs more affordable housing due to the rise of homelessness and an outrageous real estate market.

These multifaceted, interdependent questions are beyond my ability to answer in this essay, but I’ll instead mention a glimpse of redemptive hope that immediately shone like the risen sun through the charred wasteland following the firestorms. The trauma of the wildfires put everything into perspective, including possessions and politics, as I watched neighbors quickly unite to help one another navigate the aftermath and recovery together. Within a few hours of the onset of the fire, our community center was inundated with so many donations that the volunteers were unable to manage it all and had to hand it over to Salvation Army to sort and to distribute to families who had lost their homes. Residents who had lost their homes in previous wildfires immediately sprang into action to address urgent needs, while other volunteers began helping with the lengthy process of recovery. Neighbors checked on one another to make sure they knew about water advisories, especially attending to the elderly. Still others opened online forums to offer advice and assistance. Instead of the “still sad music of humanity,” I witnessed praiseworthy poetry of rebirth — of Christian stewardship at its magnanimous, altruistic best. At a time when national rhetoric has reached a fever pitch of divisiveness, I’m grateful to report that such divisions quickly evaporated, as I watched a community in need rise from the ashes because neighbors came together to bear one another’s burdens as they began to grieve, to recover, and to rebuild.

These glimpses of resurrection, coupled with Mahon’s poem, oddly reminded me of the tradition of pastoral elegies in English literature, where the death of a poet’s friend causes an outpouring of such immense sadness that it encompasses the personified grief of nature as well. Returning to the question of poetry’s power or powerlessness that I mentioned earlier, the elegy “In Memory of W.B. Yeats” charts Auden’s journey through mourning as he deals with the loss of the greatest poet of the twentieth century, at a time when Europe stood on the brink of the second World War — a liminal moment that resonates with the uncertainty of our own time. Though he employs reconfigured urban and suburban imagery, Auden nonetheless alludes to the tradition of pastoral elegies made famous by Percy Shelley’s “Adonais” and especially by John Milton’s “Lycidas.”[5] The restorative images of rebirth at the conclusion Auden’s elegy echo the redemptive conclusion of Milton’s poem and also demonstrate the transformative power of the poetic voice:

Follow, poet, follow right

To the bottom of the night,

With your unconstraining voice

Still persuade us to rejoice;With the farming of a verse

Make a vineyard of the curse….

In the deserts of the heart

Let the healing fountain start,

In the prison of his days

Teach the free man how to praise.[6]

Even more powerfully for those who have recently suffered the loss of a home or the yet more devastating loss of a loved one, John Milton dives deep into human empathy as he grieves for his friend who drowned, but then beautifully reminds us of the glory of the resurrection — like the risen sun upon the ocean, like the Son who walked upon the water itself:

…weep no more,

For Lycidas, your sorrow, is not dead,

Sunk though he be beneath the wat’ry floor;

So sinks the day-star in the ocean bed,

And yet anon repairs his drooping head,

And tricks his beams, and with new spangled ore

Flames in the forehead of the morning sky:

So Lycidas sunk low, but mounted high

Through the dear might of him that walk’d the waves….Thus sang the uncouth swain to th’oaks and rills,

While the still morn went out with sandals gray…

And now the sun had stretch’d out all the hills,

And now was drop’d into the western bay;

At last he rose, and twitch’d his mantle blue:

To-morrow to fresh woods, and pastures new.

These poems are generous gifts indeed. May we journey through grief into resurrection joy this Lenten season, ever mindful of the homeless, the friendless, and the forgotten — as my father often prayed — ever mindful of the great restoration glory of a new heaven and a new earth that will one day break through the cyclicality of history’s painful repetitions until we hear the voice of the Beloved that we have long been waiting for — the promise that all creation awaits, that all will be made new.

[1] I’m grateful to Jenny Sharpe at UCLA, as I recall her using these cracked mirror metaphors to describe postmodern art, where the original and the copy become indistinguishable.

[2] The grandmothers who “gazed at a still pond/ And knew no pain” exist in a frozen stasis of unreality. How could anything truly be still and lacking pain, unless it is dead? And now we are back to the very beginning of the ekphrastic enigma because it is art, and it is “still” in its timeless transcendence, but that pesky word “still” reminds us of all the paradoxical multivalences at stake.

[3] The cyclicality of history is also mentioned in the nineteenth-century Christmas hymn, “It Came Upon a Midnight Clear,” which emphasizes a postmillennial vision as well as an Arcadian one, though the lyrics are often altered to tone this down:

For lo! the days are hastening on,

By prophet bards foretold,

When with the ever-circling years

Comes round the age of gold.

[4] I’m grateful to Mim Lundgren for help in translating this somewhat nonsensical Norwegian phrase.

[5] John Berryman’s short story “Wash Far Away” describes a professor in mourning who attempts to teach “Lycidas” to his students, though his students instead help him see the poem afresh and hear the silenced voice of his friend.

[6] What does it mean to be a poet? To be free? Another beautiful answer to this question occurs in Seamus Heaney’s elegiac poem, “Casualty,” which draws parallels between the rhythms of fishing and the rhythms of poetry, and asks how to choose freedom and life in the face of danger and death. Compare it with Mahon’s moving poem, “Afterlives,” which also addresses conflicts in Northern Ireland, a poem introduced to me by Martin Griffin. Interestingly, Mahon was influenced by Auden, and both poets were profoundly influenced by Yeats, who of course influenced Heaney as well. It’s also worth noting that Yeats, Heaney, and Mahon are all Irish poets, though with varying Christian identities, and then Auden is the odd man out—an English poet (and Anglican) who spent some time in Southern California, learning about spirituality, pacifism, and yoga with his friends Christopher Isherwood and Aldous Huxley.