Welcome to our third and final installment of the Mockingbird Reader’s Guide to A Separate Peace. If you’d like to catch up, you can click through to find Part I and Part II.

Forgiveness

The turning point of our novel finds Gene in the barren “death landscape” of Vermont as he searches for Leper Lepellier, gone A.W.O.L. from the army.

Chapter 10 is the only chapter in the novel not set within the bounds of Devon, and Gene’s separation not only from Devon but also from Finny—from light, goodness, and peace—only adds to the “bleak, draughty train ride,” the “damp depot,” and the “frozen hillside.” Vermont is a land of snow and death that Gene must journey through to find Leper, the outcast.

Amidst this frozen tundra, Gene finds one sliver of grace:

Everything else was sharp and hard, but this Grecian sun evoked joy from every angularity and blurred with brightness the stiff face of the countryside. As I walked briskly out the road the wind knifed at my face, but this sun caressed the back of my neck.

A Grecian sun might seem an odd thing to find on a winter day in New England, but the description immediately brings to mind the elusive joy of the Winter Carnival that Gene has just left behind—the moment when Finny places a wreath on Gene’s head in triumphant victory, as the sun god Apollo did for so many other victorious athletes. This Grecian sun follows Gene even in the land of death, and when he arrives at Leper’s house, Gene sits “in a place at the middle of the table, with my back to the fireplace. There at least I could look at the sun rejoicing on the snow.” Even in the midst of the shadows, Gene carries the joy of light with him. But here, the sun cannot melt the snow.

There is an irony in the code that Leper gives to Gene—that he is “at Christmas location.” Gene recognizes that Leper means his home in Vermont, the northernmost point, the North Pole of their shared geography, but this Christmas location is devoid of the hope and glory expected of the season. This location is, instead, where Gene must finally confront the savagery of his soul.

In Leper’s home, Gene comes face-to-face with his friend’s insanity. Leper has deserted the army rather than receive a Section 8 discharge for mental instability. Instead of pity for Leper, Gene feels only apprehension for himself:

Fear seized my stomach like a cramp. I didn’t care what I said to him now; it was myself I was worried about. For if Leper was psycho it was the army which had done it to him, and I and all of us were on the brink of the army.

Here, at this barren Christmas location, Gene faces the reality of the law of the world. What has happened to Leper can and will happen to Gene, to Brinker, to Finny, to all of the Devon boys who enter the world’s war. Gene lashes out against this fear, protecting himself by shutting Leper out, and it is in this moment that Leper shows Gene that he’s always known Gene’s true nature:

You always were a lord of the manor, weren’t you? A swell guy, except when the chips were down. You always were a savage underneath … like that time you knocked Finny out of the tree.

Gene leaps from his chair, cursing Leper, shoving his foot against the rung of Leper’s chair and causing him to collapse against the floor. Leper’s recognition of the darkness of Gene’s nature reveals that darkness to an even greater extent—in being named a savage, Gene cannot help but act as a savage. He still loses control to the darker side of his heart, even after he has seen the destruction wrought on Finny.

Although Gene realizes his mistake more immediately this time and stays for lunch after Leper’s prodding, Gene begins to recognize this in-aptly named Christmas location—devoid of salvation—as his own sort of hell:

I did not have New England in my bones; I was a guest in this country … and I could never see a totally extinguished winter field without thinking it unnatural. I would tramp along trying to decide whether corn had grown there in the summer, or whether it had been a pasture, or what it could ever have been, and in that deep layer of the mind … I knew that nothing would ever grow there again.

Surrounded by so much barrenness, Gene cannot conceive—cannot even imagine—rebirth. And as he once again comes face-to-face with Leper’s insanity, he realizes that in this dark place, there is no separation between Leper’s darkness and his own:

This exposure drew us violently together; I was the closest person in the world to him now, and he to me.

Gene sees his own turmoil reflected in Leper, sees his own dark and twisted heart reflected in Leper’s dark and twisted mind, and he runs, fleeing Leper, fleeing Vermont, fleeing the ice of hell itself in search of the one light he knows.

Chapter 11 begins with Gene’s admission:

I wanted to see Phineas, and Phineas only. With him there was no conflict except between athletes, something Greek-inspired and Olympian in which victory would go to whoever was the strongest in body and heart. This was the only conflict he had ever believed in.

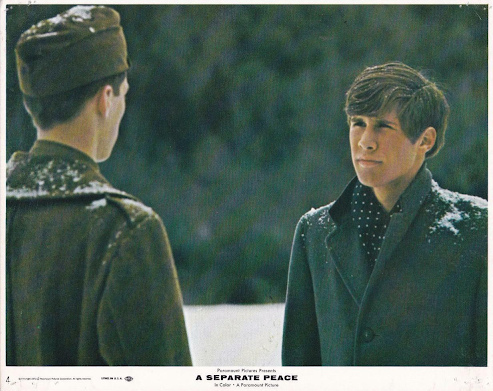

After the hellish landscape of Vermont, Gene needs the light and inspiration of his friend. He finds Finny in the middle of a snowball fight, “the lights and leaders of the senior class, with their high I.Q.’s and expensive shoes … pasting each other with snowballs.” Gene knows that only Finny could have created such a gathering, such a spot of joy amid the gloom of winter. Once again, the light of grace shines through the darkness, and Gene is engulfed in the game.

Later that day, Brinker and Finny ask about Leper, and through Brinker’s energetic questioning, Gene gives them the truth. In a nice bit of foreshadowing for the rest of the chapter, Gene describes:

Brinker had closed with such energy, almost enthusiasm, on the truth that I gave it to him without many misgivings. The moment he had it he crumbled.

Brinker the Lawgiver is direct in his pursuit of truth and justice, as the rest of the chapter shows all too vividly, but here we see that the truth without mercy can be too horrible to know. As the reality of Leper’s condition pervades the room, the reality of the rest of the war enters in, too. The separate peace that Finny had reestablished with his return to Devon begins to fade, as much of what remains at the school becomes recruited for war.

On the final night in Gene and Finny’s dorm room, Finny tells Gene that he has seen Leper on campus that day. Like Gene’s experience in Vermont, Finny’s glimpse of Leper’s insanity drives away all of the illusions of his made-up war. He tells Gene, “Anyway, then I knew there was a real war on.” If Leper could change as dramatically as he has, Finny also has to admit to Gene the truth of the war. Finny tells Gene that he did a beautiful job in the Olympics, and Gene praises Finny for being the greatest news analyst who ever lived. In their final night of camaraderie and happiness,

The sun was doing antics among the million specks of dust hanging between us and casting a brilliant, unstable pool of light on the floor. ‘No one’s ever done anything like that before.’

That instability of light foreshadows how quickly it will fade against the encompassing darkness that Brinker brings when he and three cohorts arrive at their room later that night.

The trial scene takes place in the First Building, over which is written a Latin inscription: “Here Boys Come to Be Made Men.” The loss of innocence culminates in the Assembly Room, where Brinker has created a court of classmates to investigate Finny’s accident—and to put Gene on trial. Brinker’s excuse is that for Finny’s good, and for Gene’s own good, all should be out in the open:

He’s enjoying this, I thought bitterly, he’s imagining himself Justice incarnate, balancing the scales. He’s forgotten that Justice incarnate is not only balancing the scales but also blindfolded.

As we have seen with Brinker’s character time and again, his pursuit of the law is unrelenting and merciless. His pursuit literally blinds him to the pain that his self-righteous justice will bring. And Finny, who has never been capable of dishonesty in his life, lies three times to save Gene.

Despite it all, Brinker marches forward, finally calling for an alternate witness:

No one said anything. Phineas had been sitting motionless, leaning slightly forward, not far from the position in which we prayed at Devon. After a long time he turned and reluctantly looked at me. I did not return his look or move or speak. Then at last Finny straightened from this prayerful position slowly, as though it was painful for him. ‘Leper’s here,’ he said in a voice so quiet, and with such quiet unconscious dignity, that he was suddenly terrifyingly strange to me.

Like Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane, Phineas has realized that the law must have its way. No matter how much he wants to protect Gene, no matter how much he wants to live in his world of a separate peace, the Lawgiver will never stop. Only Finny’s sacrificial act of his own freedom and happiness by revealing the truth of that day at the Edenic tree will fulfill the law’s demands. And so he prays, and he gives himself over to his fate.

Leper’s testimony uses the imagery of war and hellfire to describe what he saw at the tree:

I could see both of them clearly enough because the sun was blazing all around them … and the rays of the sun were shooting past them, millions of rays shooting past them like—like golden machine-gun fire … The two of them looked as black as—as black as death standing up there with this fire burning all around them.

The hellscape of the fall is on full display with Leper’s mad words, and as he confirms the question at hand—that Gene was indeed in the tree with Finny and that Gene’s movement did indeed throw Finny from the limb—Finny breaks:

‘I don’t care,’ he interrupted in an even voice, so full of richness that it overrode all the others. ‘I don’t care.’

Brinker calls after him as Finny starts from the room, shouting that they don’t have all the facts yet. Finny swings and curses Brinker before plunging out the doors and in the darkness of the night,

These separate sounds collided in the general tumult of his body falling clumsily down the white marble stairs.

Doctor Stanpole reassures Gene that Finny’s re-broken leg is a cleaner break and a simple fracture, a bone that can easily be set and fixed. Gene, in shock and completely irrational, follows Finny and the adults to the Infirmary, where he waits outside the window until Finny is alone. He tries to climb through the window until he realizes that Finny, just as overwhelmed with emotion, “was struggling to unleash his hate against me”:

‘You want to break something else in me! Is that why you’re here!’ He thrashed wildly in the darkness, the bed groaning under him and the sheets hissing as he fought against them.

Finny is trapped, bound up not only by his broken leg but by the knowledge of Gene’s evil deed. Just as the alliterative Super Suicide of the Summer Session hissed like a snake around the boys at the beginning of the novel, so the snake appears again in the hissing sheets binding Finny to the bed and the knowledge of the evil in the world. He lunges out towards Gene, falling half-way to the floor, and all Gene can focus on is the knowledge that he had not hurt himself again. Gene has just enough control, in the face of what he has done to Finny, to climb back out of the window, all the while saying, “I’m sorry, I’m sorry, I’m sorry.” Gene can offer nothing else but the bottom of his emotions, of his sorrow, his regret, and his shame.

When Gene returns with Finny’s suitcase the next day, he tries to reassure himself by thinking of all of the horrible events occurring in his world:

After all … people were shooting flames into caves and grilling other people alive, ships were being torpedoed and dropping thousands of men in the icy ocean, whole city blocks were exploding into flame in an instant. My brief burst of animosity, lasting only a second, a part of a second, something which came before I could recognize it and was gone before I knew it had possessed me, what was that in the midst of this holocaust?

As soon as he sees Finny, however, Gene knows how false this line of reasoning is. The war of good and evil within his own soul is more powerful than any external war, than any horrific holocaust. It is more powerful because it is his own heart and soul that are at stake, and no chain of reasoning can convince him otherwise.

But it is Finny’s confession that surprises Gene the most. Finny, who admits that his game-playing about the war’s existence was just a charade, has been writing to every war office in the country and then in the world to ask if someone would let him enlist. Finny cannot conceive of not being a part of the biggest event—the biggest game—in the world. He has to be a part of a team. And it is then that Gene reveals just how much he knows of Finny’s heart:

‘Phineas, you wouldn’t be any good in the war, even if nothing had happened to your leg … They’d get you some place at the front and there’d be a lull in the fighting, and the next thing anyone knew you’d be over with the Germans or the Japs, asking if they’d like to field a baseball team against our side. You’d be sitting in one of their command posts, teaching them English. Yes, you’d get confused and borrow one of their uniforms, and you’d lend them one of yours. Sure, that’s just what would happen. You’d get things so scrambled up nobody would know who to fight any more. You’d make a mess, a terrible mess, Finny, out of the war.’

For Gene, it is no longer about the shame and guilt he feels over Finny’s fate. All that matters now for Gene is that Finny sees his own goodness, sees how much better he is than a world of war and enemies and territories. That deepest of human desires—the need to be both fully known and fully loved—is fulfilled in Gene’s knowledge of Finny’s character. Gene knows Finny completely and, in showing Finny how well he knows him, shows him how much he loves him.

And then Finny offers Gene the same gift in return:

‘It was just some kind of blind impulse you had in the tree there, you didn’t know what you were doing. Was that it?’

‘Yes, yes, that was it. Oh that was it, but how can you believe that? How can you believe that? I can’t even make myself pretend that you could believe that … Tell me how to show you. It was just some ignorance inside me, some crazy thing inside me, something blind, that’s all it was.’

He was nodding his head, his jaw tightening and his eyes closed on the tears. ‘I believe you. It’s okay because I understand and I believe you. You’ve already shown me and I believe you.’

The absolution that Gene has sought for the whole novel comes wrapped in those words—“I believe you.” Finny, in his turn, shows Gene how fully he knows Gene’s character—in all its dark and blind impulses—and that he loves him just the same. With his belief, he offers Gene what Gene has sought for so long: the forgiveness of his best friend.

The rest of the day passes easily for Gene—his trigonometry problems even appear to solve themselves on his paper—as he finally receives the freedom of Finny’s grace. Gene spends the day enjoying his forgiveness before returning to the Infirmary for the update on Finny’s surgery. And there, on the bench outside the office, Dr. Stanpole finds Gene to tell him that Finny is dead:

‘In the middle of it his heart simply stopped, without warning. I can’t explain it. Yes, I can. There is only one explanation. As I was moving the bone some of the marrow must have escaped into his blood stream and gone directly to his heart and stopped it. That’s the only possible explanation. The only one.’

Phineas dies of a broken heart when he comes face-to-face with the evil in the world. As Gene said earlier on, “With him there was no conflict except between athletes, … in which victory would go to whoever was the strongest in body and heart. This was the only conflict he had ever believed in.” Finny lived in a world where hearts were pure and minds were strong and souls were made of sunlight. He believed in a world without darkness, without war, without enemies, and without hate. In fulfilling the requirements of the law, Finny comes face-to-face with the evil, not just in the world, but in the heart of his own best friend.

With Finny’s death, war fully encompasses Devon. Jeeps roll into town, officers take the place of the Headmaster, and Gene and the other boys choose their branches of service. But for Gene, the war no longer holds any kind of power:

It seemed clear that wars were not made by generations and their special stupidities, but that wars were made instead by something ignorant in the human heart.

Gene knows, better than any other boy at Devon, the ignorance of the human heart:

I was ready for the war, now that I no longer had any hatred to contribute to it … Phineas had absorbed it and taken it with him, and I was rid of it forever.

Gene is freed through Finny’s sacrifice and through Finny’s death but most of all through his own love for Finny:

My war ended before I ever put on a uniform; I was on active duty all my time at school; I killed my enemy there.

Gene’s enemy was not Finny but his own selfish nature. His jealousy, his guilt, and his hate are washed away by his love for Finny and by Finny’s love for him. Fully known and fully loved—unconditionally. Gene steps forward into the world’s war “as well as my nature, Phineas-filled, would allow.” Surrounded by the truth of his separate peace—of the knowledge of the real enemy and the only force powerful enough to defeat death—Gene leaves behind his boyhood and enters the world awake to the knowledge of evil and protected by the knowledge of love.

COMMENTS

One response to “A Mockingbird Guide to A Separate Peace: Chapters 10-13”

Leave a Reply

Thanks for this series. It prompted me to re-read the book for the first time since high school. When I first read it, I was the age of the boys at Devon; now, I’m the age of Gene at the beginning of the book, looking back. It’s quite something to see how a work of literature can strike you differently at different ages…