To be loved is to be known, the saying goes. Or as Tim Kreider memorably puts it, “if we want the rewards of being loved we have to submit to the mortifying ordeal of being known.” This is what we believe makes God’s love so miraculous, so fundamentally gracious.

Of course, when it comes to other human beings, this kind of thing is risky business. Because getting to know someone in all their unkempt reality, i.e., beyond the surface facsimile, often provokes a feeling opposite to love. The problem comes when we think we know someone fully but don’t, as is often the case with our so-called “loved ones”(!) or anyone for whom we’ve written the script.

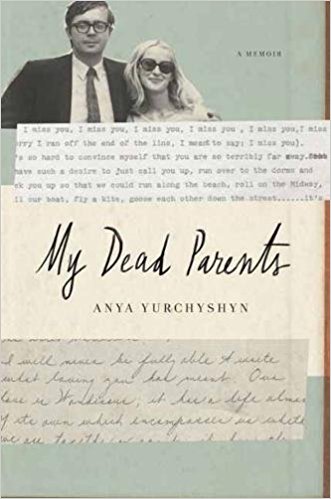

In a recent sermon, my friend Marilu Thomas paraphrased just such an instance from Anya Yurchyshyn’s memoir, My Dead Parents, and it was too rich not to share:

When her mother died of alcoholism and her father was killed in a car accident, Anya was actually relieved. She had experienced her father as cold and aloof and her mother as ineffectual and anxious. Her parents’ disdain and contempt for one another was on display throughout her life, and she blamed her own anxiety and low self-esteem on them.

When her mother died of alcoholism and her father was killed in a car accident, Anya was actually relieved. She had experienced her father as cold and aloof and her mother as ineffectual and anxious. Her parents’ disdain and contempt for one another was on display throughout her life, and she blamed her own anxiety and low self-esteem on them.

When Anya was cleaning out her parents’ house, however, she was stunned to find a box of sweet, vulnerable love letters the two had exchanged. Her father had written, “Whenever I leave you, there is an emptiness inside me, a true aching of the heart.” Her mother had responded, “Our love is wondrous; it has a life almost of its own.”

Anya was in shock. Who were these people? She made it her mission to understand who her parents truly were by visiting the Pennsylvania neighborhood where her mother grew up. She walked the grounds of the University of Chicago where they had met. She discovered that her mother’s childhood had been heartbreakingly tragic, filled with trauma and abandonment. Her heart softened in compassion for the girl and woman who had been the mother she didn’t know.

She then flew to her father’s ancestral home in the Ukraine. Much to her surprise, she discovered that he was regarded as something of a hero. You see, after the war he had returned early and often to help rebuild the devastated town. What she had thought of as her father’s selfish absenteeism turned out to be an unselfish devotion to those he had left behind, a fact she didn’t know about him.

Moreover, before she was born, her parents lost her one year old older brother to pneumonia, which etched the pain into the marriage. They did not tell her of his existence until she was ten years old. Anya writes:

“Devastating as it was, this information was a gift, shining a light into the murky corners of my childhood. My father policed my behavior so intensely not because he was a dictator, but because he was terrified of losing another child—his anger was misplaced grief. My mother wasn’t weak—she’d had to be unimaginably strong to survive her childhood, lose her parents, son and husband. I was the product of complicated people… Today I am proud to be their daughter—a person who’s replaced pity with compassion. That compassion opened the door to the emotional prison where I’d long kept my parents. And in turn, it freed me.”

To be clear, Anya’s case is not everyone’s. Sometimes the backstory has a feel-good element, but sometimes the truth turns out to be uglier than we had presumed. Either way, we write others off at our own peril, even when we feel we have every reason to–even when we’ve been forced to bear the brunt of their shortcomings.

Perhaps faith is simply the willingness to admit we may not possess all the facts, not when it comes to other people and certainly not when it comes to God. Or maybe it’s trust that the one who does have all the facts, the good the bad and the ugly, is more interested in ransoming those in captivity to their own backstories than judging them.

If that sounds like too big a risk for a battered heart to take, well, it could be there’s comfort in the fact that some mortifying ordeals are love letters in disguise.

COMMENTS

8 responses to “Pity, Compassion, and the Emotional Prison Where She Kept Her Parents”

Leave a Reply

DAVE! Give Marilu a hug from Houston! This was fantastic!

????????❤️

“Anger is misplaced grief”…inasmuch as we are able to think like this everything changes…

Faith is the assurance of things hoped for…confidence that all our backstories are ultimately irrelevant…that all is forgiven…I hope so.

I don’t mean to be negative, because I really liked the piece, and the grace she found by delving into her parent’s humanity, and seeing them for the complex people–not wholly broken, or contemptible–they were. But…

I have to wonder if there is some reconciliation that, because of the nature/habits of the people involved, is impossible without death or barely less extreme circumstances. Here I’m thinking of an elderly man I knew once, who was stricken with grief over the fact that, in his years as a violent drunk (his term) he had physically abused his wife over and over. She eventually left, and then she died. He continued to drink until a terminal cancer diagnosis and the subsequent treatment forced sobriety on him. Now sober, he was a bundle of shame and grief for how he’d lived his live, and especially how he’d treated her–particularly the fact that he never had the chance to say he was sorry, or tell her he really did love her. I prayed and prayed with and for that man, but there were no easy or simply solutions. He was repentant once freed of the demon of alcoholism. I’m sure part of him was sorry the whole time. But I don’t see where, given this background, the hope for redemption was in this life.

Likewise, I think about people who must separate themselves from others. I think “toxic people” get’s thrown around a lot (toxicity in my mind comes from sin, so we’re all toxic to some extent), nevertheless, sometimes separation is the only means people have to stop new wounds from being made. And the cessation of deep wounding is, I think, a prerequisite for true reconciliation. Though not, I think, for compassion and forgiveness (sometimes from a distance).

Actually, to reword a bit: the cessation of wounding is necessary for reconciliation, and for compassion and forgiveness. But one can have compassion and offer forgiveness from a distance, when being close without a person being repentant and being willing to change would be the occasion for greater wounds.

I agree 100%, Jody. Definitely didn’t mean to suggest that contemptible attitudes and actions don’t exist, or that people should prostrate themselves to those who have hurt them. We are not God, and redemption is not ours to engineer. And I think you’re right: that her folks were dead–and not capable of continuing the behavior in question–is clearly a big part of what made this “reconciliation” possible.

Part of what I found so moving about the story was that the breakthrough wasn’t the result of her consciously adopting a wiser strategy (lest it become a new prescription), but rather, her receiving what she refers to as a gift. In that final sentence I tried to suggest that where hope in horizontal forms of reconciliation fails (or is simply unavailable/unwise/dangerous), the hope of Calvary still remains–even in extreme circumstances.

This is all so true. And even if you are not able to find out all the family secrets, you can probably assume that folks who wound people probably have some serious trauma in their background that has never been dealt with.

Also these patterns most often get passed on in one form or another…

YOUR CHILDHOOD WOUNDS MAY BE HURTING YOUR MARRIAGE

http://www.christianitytoday.com/women/2018/january/your-childhood-wounds-may-be-hurting-your-marriage.html

One can repent and believe all day long but if the source isn’t uncovered, it often does not get fully healed. And then you walk around feeling like a worm cuz you “keep doing the thing you don’t want to do. A lot of change doesn’t happen without self-awareness of the source.

Which is why, this… 🙂

WHY EVERYONE SHOULD BE IN THERAPY INCLUDING YOU

http://qideas.org/articles/why-everyone-should-be-in-therapy-including-you/

Thank you for this reminder. Many of us are missing pieces of our parents’ lives or others’ lives in general that would explain them better, that we might be more forgiving. I find this in my office when people tell me their childhood and I learn then why they are who they are today. The healing comes when they themselves can remove their armor and be more vulnerable. Through epigenetics we now learn how some really serious traits can be passed down . Jesus simply forgave. Why is this so hard…….

So true. (See my post above.)

When you don’t understand why, it’s harder to have compassion but there must be a way to this because not everyone gets to know the missing pieces.

Epigenetics is quite fascinating. The On Being podcast has a fascinating episode covering Dr. Rachel Yehuda’s research in epigenetics.