We live in a land of heightened security. A world of high-tech surveillance systems, smart doorbells, traffic cameras, and face recognition software. It feels like most of our time at work is retrieving six-digit codes. And yet, it feels like our world has never been less secure than it does right now. Personal safety fears are at a three-decade high. Almost half of Americans feel unsafe walking alone at night near their home. In some ways, increasing our security seems to have increased our fears. As Billy Joel famously sings, “If you’re so smart, tell me why are you still so afraid?”

Why, you ask? Well, for starters, fear is our most primal emotion. It’s built into our DNA. Our ancient ancestors did not have the luxury of having only fear itself to be afraid of, but also wolves. Fear was what kept you alive back then. And little has changed. With a few more weeks of pool season left, it feels like the only thing keeping my one-and-a-half-year-old alive is my fear which prompts me to grab him as he launches himself into the deep end. Fear’s power is in its ability to show how little control we have over everything — our loved ones, our careers, our health. The reason why anxiety is so unconquerable is because of its parasitic, shapeshifting nature. As soon as one fear subsides, another takes its place. Whether you are single, married, a parent or grandparent, there is always something to be afraid of.

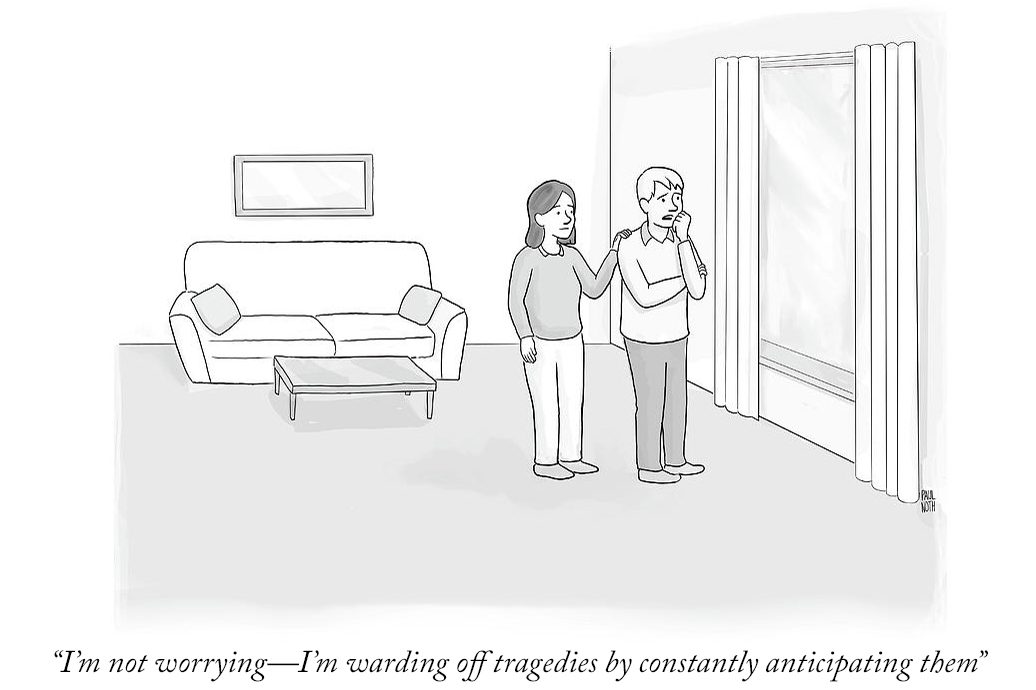

It often feels like anticipating danger can keep it at bay, but it’s not long until our fears become more real than the threats themselves. In a recent Atlantic article, when asked what would happen if two ten-year-olds played in a local park without adults around, half the people thought the kids would get abducted. In response, Jonathan Haidt (along with two other journalists), wrote, “These intuitions don’t even begin to resemble reality.” He then references Warwick Cairns’ study from his book How to Live Dangerously, which states that kidnapping in the United States is so rare that a child would have to be outside unsupervised for, on average, 750,000 years before being snatched by a stranger. Perhaps that number seems outlandish. Then again, it raises the question: Is our paranoia a greater threat to us than the things we’re afraid of? Haidt and company continue with a helpful comment:

The tendency to overestimate risk comes with its own danger. Without real-world freedom, children don’t get the chance to develop competence, confidence, and the ability to solve everyday problems. Indeed, independence and unsupervised play are associated with positive mental-health outcomes.

The key word, I think, is freedom. What does “real-world freedom” actually look like? According to the article, it can best be defined by what it is not. Freedom is a lack of control. It involves a lack of supervision and structure. It looks like parents not knowing what the kids in the next room are actually talking about or what exactly happened on the playground that prompted a fight. It looks like risking one’s child to injury, bad influences, bullying, even abduction. In a world in which one of the worst things a parent can be called is “neglectful,” real-world freedom looks terrifying.

And yet, what happens when children are given real-world freedom? Perhaps a few more broken bones but far more memories. More often than not, kids left on their own will look much less like The Lord of the Flies and more like The Sandlot. Albeit, the humor will be crass, but the joy will be brilliant. Generally speaking, kids are more likely to be more resilient and more confident. (And the parents much less stressed out!) It turns out the old trope might be true, that with great risk comes great reward.

As frightening as the world may seem (or perhaps actually is), when we turn our gaze heavenward we might be surprised by what we find. As a heavenly father, God is not a helicopter parent. As a shepherd, he does not raise his sheep in cages but in the wild, allowing them to roam free-range. This freedom allows them to get lost, get injured, and make mistakes (whether they learn from those mistakes or not!). God may be ever watchful and ever present, but his heavenly hand does not come from above to intervene whenever we face a foe or a threat (at least, not in the way we think). As much as we want him to, he does not stand between us and suffering. He permits us to get injured and to even inflict injury on others.

Why would God practice this art of willfully negligent parenting? Because God’s main goal is not protection but redemption. For him, getting lost is a precursor to getting found. Getting hurt is an antecedent to getting healed. Suffering is a harbinger of perseverance. Dying is a prerequisite to being resurrected.

When one looks to the church, they often find more fearmongers than freedom preachers. Proclaiming God’s grace without any disclaimers feels far too risky. We can’t honestly tell people they’re actually free, otherwise, they’ll be knee-deep in tomfoolery by lunchtime. And yet, as Robert Capon once said, “If we are ever to enter fully into the glorious liberty of the children of God, we’re going to have to spend more time thinking about freedom than we do. The church, by and large, has had a poor record of encouraging freedom.” If we dare dip our toes into its waters, we just might discover that the water is just fine.

In his book On the Grace of God, Justin Holcomb recounts a story about Abraham Lincoln who went to a slave auction one day and was appalled at what he saw:

He was drawn to a young woman on the auction block. The bidding began, and Lincoln bid until he purchased her — no matter the cost. After he paid the auctioneer, he walked over to the woman and said “You’re free.” “Free? What is that supposed to mean?” she asked. “It means you are free,” Lincoln answered, “completely free!” “Does it mean I can do whatever I want to do?” “Yes,” he said, “free to do whatever you want to do.” “Free to say whatever I want to say?” “Yes, free to say whatever you want to say.” “Does freedom mean,” asking with hope and hesitation, “that I can go wherever I want to go?” “It means exactly that you can go wherever you want to go.” With tears of joy and gratitude welling up in her eyes, she said, “Then, I think I’ll go with you.”

While the toxicity of fear leads to ulcers, high blood pressure, and paralysis, the joy of freedom gives birth to peace, gratitude, and devotion. Blind faith is the opposite of a smart doorbell. It looks like utter foolishness and could lead to all kinds of damage and injury. And yet, the freedom of the gospel is the only thing that will actually help us be less afraid. It is the perfect love that casts out fear. After all, in an insecure world, the only thing that is truly secure is our salvation.