This is Mockingbird, so you know that even though we’ve already done some recent literature-themed lists (e.g., 21st-century novels and devotional poems), it was inevitable that we would get around to a list of our favorite works of theology. Sure, these may not quite constitute summer beach read material for many, but there’s plenty of powerful, life-changing theology represented here (listed chronologically). Enjoy!

The Freedom of a Christian (1520), by Martin Luther: If you’re going to read one book by Luther, it shouldn’t be The Freedom of a Christian. That honor should go to the Small Catechism for its faithful explanations and pithy language. But Freedom comes in second. It’s early Luther at his best — no deep polemic like in Bondage of the Will, just utterly clear writing about the nature of the Christian life. It’s all there: law and gospel, the Happy Exchange, justification by faith, two kingdoms, vocation, and more. This is how to teach the language of faith. – Ken Jones

The Bondage of the Will (1525), by Martin Luther: This was my first deep dive into Luther. And, oh, what a dive it was! I only had to read a few pages to realize I was out of my depth. It was a lot like what I think getting the bends in scuba diving must be like. In the pages of this polemic, I encountered a Christian punch-drunk on the God who is really God. It was distressing to realize how much of my talk about God was nothing more than pious platitudes. However, once I could breathe in the depths of Luther’s theological world, I found myself face-to-face with a faith worth practicing. – Ryan Cosgrove

The Cost of Discipleship (1937), by Dietrich Bonhoeffer: “Cheap grace,” grace available at the low, low price of assent to the correct theological system, is a specter that haunted Protestants in 1930s Germany and one that haunts us now. Against “grace at cut prices,” Bonhoeffer reminds us that grace is never a free-floating entity detached from union with Christ, who bids us come and die when he calls us. Grace is completely free, and it costs everything: “Only the believing obey, and only the obedient believe.” This is not a cute paradox; it’s reality of life with Christ. – David Clay

The Big Book of Alcoholics Anonymous (1939), by Bill W. (et al.): I can’t tell you exactly how or when or why God chooses to intervene in our lives, but if you’ve been around 12-step programs long enough, you know he does. I once heard a priest say that sin is not so much a crime to be punished as a wound to be healed, but even if that’s true, you’d have to believe in a robustly personal God to ever hope that you could be healed. Though not explicitly Christian, the God we find in The Big Book is indeed the kind of God who heals. While the first third outlines the program, the rest of the book (now in its fourth edition) is a compilation of astonishing tales of recovery from every kind of alcoholic under the sun. In other words, it’s a book of miracles, some of the most compelling evidence you’ll ever get outside of the Bible that God is actively involved in the salvation of hopeless sinners. If you spend enough time immersed in those stories, you can’t help but start to believe that there is indeed “a Power greater than ourselves [that can] restore us to sanity.” – Ben Self

Jesus and the Disinherited (1949), by Howard Thurman: Thurman explores Jesus’ life and teachings as lifesaving against the fear and oppression experienced by the “disinherited,” or those with “their backs against the wall.” He explains: “The awareness of being a child of God tends to stabilize the ego and results in a new courage, fearlessness, and power … A man’s conviction that he is God’s child automatically tends to shift the basis of his relationship with all his fellows.” Thurman constructs his argument not only from deep study, but also knowledge imparted by his grandmother that the Creator of existence (“who holds the stars in their appointed places, leaves his mark in every living thing”) also created him. Knowing this, he explained that he could “absorb all the violences of life.” This is the book that said exactly what I needed to hear: that I am a child of God (so are you), and that God, the Creator of the universe, is intimately concerned with my spirit. – Sarah Gates

Mere Christianity (1952), by C. S. Lewis: Choosing Mere Christianity is essentially just holding a place for any of Lewis’ theological works — The Screwtape Letters, The Great Divorce, etc. It’s kind of cliché, in fact, to put Lewis on a list like this, the sort of embarrassment that Lewis would call symptomatic of a desire to be in “the inner ring.” So let’s cut through the posturing and be sincere: Lewis can mix love and logic in a way that makes the heart strangely warm. Beyond the stale justifications of God’s existence that make up modern Christian apologies (what Francis Spufford called “the most uninteresting of God’s attributes”), or the metaphysics of the medievalists trapped in the cosmos of their own creation (what Jüngel would call a problem of ontology), Lewis writes of the way things are and the way things should be with clarity, charity, and insight. “If I find in myself a desire which no experience in this world can satisfy, the most probable explanation is that I was made for another world.” – Bryan Jarrell

Mere Christianity (1952), by C. S. Lewis: Choosing Mere Christianity is essentially just holding a place for any of Lewis’ theological works — The Screwtape Letters, The Great Divorce, etc. It’s kind of cliché, in fact, to put Lewis on a list like this, the sort of embarrassment that Lewis would call symptomatic of a desire to be in “the inner ring.” So let’s cut through the posturing and be sincere: Lewis can mix love and logic in a way that makes the heart strangely warm. Beyond the stale justifications of God’s existence that make up modern Christian apologies (what Francis Spufford called “the most uninteresting of God’s attributes”), or the metaphysics of the medievalists trapped in the cosmos of their own creation (what Jüngel would call a problem of ontology), Lewis writes of the way things are and the way things should be with clarity, charity, and insight. “If I find in myself a desire which no experience in this world can satisfy, the most probable explanation is that I was made for another world.” – Bryan Jarrell

No Man Is an Island (1955), by Thomas Merton: When I lived in New York, a friend of mine had a copy of this book and passed it on to me. I kept it at work and would return to it on breaks, where it was a real respite from the grind around me. Merton’s thoughts read like nothing I’d ever heard before and made me realize how much bigger the gospel is than I’d imagined, and how God is truly in every detail and moment. The passages about solitude particularly affected me, making me feel — counterintuitively — less alone, in a city full of people. – Stephanie Phillips

The Violent Bear It Away (1960), by Flannery O’Connor: Like all of O’Connor’s work, this is about the farthest thing from a lighthearted beach read you will find. For instance, there’s a cold-blooded murder of an intellectually disabled child and the subsequent drugging and raping of the protagonist by a mysterious figure who is probably a stand-in for the devil. So what could all that possibly have to teach us about God? Well, while I wouldn’t say that God causes such terrible things to happen to us, O’Connor makes the case that God uses these horrific experiences to get our attention. Which is why she includes them. As Jessica Hooten Wilson put it in a recent podcast, O’Connor was “not trying to shock for the sake of shock … She wants to shock you because if you don’t recognize your earthliness … if your face isn’t in the sand … if you don’t realize your smallness, you’re never going to know God’s greatness.” In the end, the wounded protagonist — both a murderer and rape-victim — turns back toward the sinful city with a new sense of calling: to “warn the children of God of the terrible speed of mercy.” Jeepers! – Ben Self

Gospel and Church (1964), by Gustaf Wingren: Is this really my favorite book of theology? I’m not 100% sure. There are other books of theology I’ve enjoyed reading more (PZ’s oeuvre, for example) and there are other theology books that I agreed with more thoroughly. However, Wingren’s book is one that I keep thinking about almost a year after reading it. Part of my fondness for it is due to having studied it under the tutelage of one of my favorite Luther Seminary professors, the wonderful Lois Malcolm. But maybe the main thing that I liked about it was that there were multiple points throughout that seemed to address things that I see as big problems in contemporary mainline Protestantism in the U.S., even though it was written in Sweden in the early ’60s. Plus ça change … There are also some great Luther-derived thoughts on the freedom of our varied responses to the gospel and how that is a good thing, that we don’t actually even want a uniform response from people as much as it sometimes seems we might. I still hope to write another article drawing from this book, so I’ll just say that I think it’s very much worth reading. – Joey Goodall

God’s Being Is in Becoming (1965), by Eberhard Jüngel: I first came across this book almost twenty years ago and consider it to be a classic of the field with far-reaching consequences. Though the argument itself is a dense reading of Karl Barth’s Church Dogmatics and the doctrine of the Trinity, its thesis is quite simple: God is who he says he is. God is not unknowable or even mysterious, but one who genuinely reveals himself without remainder. There is no other god lurking behind the curtain, nor is one’s faith in God merely a human construct. – Todd Brewer

Clinical Theology (1966), by Dr. Frank Lake, the late British psychiatrist, has been an important book to me in each of its published forms. Whether the original one-volume edition, the current two-volume edition, or the more commonly available abridged edition, I’ve found Lake’s theologically informed counseling techniques explosively encouraging. In a section titled, “History-Taking Can Be Therapeutic,” Lake sums up everything I like about this book: “It is the counsellor’s opportunity to show that he is much more interested in the totality of the real person and every one of his genuine feelings and experiences, than he is about symptoms, omissions, commissions or beliefs and unbeliefs. He shows himself to be unconditionally at the disposal of the needy person, granting to his faith the same unquestioning certainty that it will be justified, and he himself accepted whatever disgrace is revealed, as the pastor himself received from Christ. Here he is putting the gospel in its ontological roots into action as maybe nowhere else in his ministry.” All I can say to that is, Amen! – Josh Retterer

Godric (1980), by Frederick Buechner: After 500 years, the Reformation’s explosive proclamation of grace has collected some dust. “Justification by faith apart from works” and “simul iustus et peccator” (the righteous person is simultaneously a sinner) can sound like abstract slogans — or worse theological banners — rather than aha-moment triggers that unleash the power of the Good News of Jesus Christ. While there are great theological books that revive these Reformation slogans (some on this list), sometimes you need to see them embodied rather than be told about them. That’s why I love Buechner’s Godric. As we hear Godric retell his story (alongside Reginald’s rosy interpretations), the flesh and blood story of this unlikely saint confronts us with the powerful mystery of how God graciously plays within the grit of our lives. What is the truth of God’s work in Godric’s life? What is the shape of God’s grace in my own life? In those around me? Read Godric alongside Luther and Forde, and let it pull you even deeper into the mystery they proclaim. – Joel Steiner

Death and Life: An American Theology (1987), by Arthur C. McGill: It’s difficult to do justice to a book that feels so harsh, but is so spiritually freeing! His images of bronze people versus the expending and needy Kingdom of God are profound. “Behind the conspicuous theme of death stands the religious problem of neediness. Neediness unifies all the little deaths we die. [It] founds Christian relationships to self, neighbor, and God, and is the flavor of Christian love.” – Ryan Alvey

Theology Is for Proclamation (1990), by Gerhard O. Forde: In many ways, Theology Is for Proclamation might just be Gerhard Forde’s magnum opus. Throughout, Forde aims to present an approach to preaching that is less about explanation or information and more about proclamation. This, to be sure, isn’t meant to downplay the importance of “giving the sense” of God’s words to God’s people (Neh 8:8). Rather, it’s Forde’s thesis that the word of God’s gospel is heard and received only insofar as it is announced in the present tense. “What the church has to offer the modern world,” he writes, “is not ancient history but the present-tense unconditional proclamation” (8). In this dense yet accessible book, the reader is engrossed in a theology of preaching that, ironically enough, shows how theology alone can’t “unmask God,” as Forde puts it (18). The profundity of the words that echo in sanctuaries isn’t necessarily due to their theological precision, as pivotal as that may be, but the triune dynamism that carries it and sustains it, ensuring that not a syllable of it returns void (Isa 55:11). As intricate and systematized as one’s theology may be, declaring theology is a task that always falls short as long as the two most important words are missing — namely, for you. – Brad Gray

The Open Secret: An Introduction to the Theology of Mission (1995), by Lesslie Newbigin: I took a class on Newbigin’s theology my last semester of divinity school, and it completely transformed my thinking about the task of ministry. Newbigin wrote countless books, but he never did so from an academic post. After returning from 30 years of missionary work in India, Newbigin penned The Open Secret, a must-read for anyone thinking seriously about what the church’s mission is. In short, Newbigin’s book proposes that “Mission” is the pattern of life the Trinity has always been practicing as the Son reveals the Father and the Spirit speaks the language of the Son. This pattern of reality, as preached and lived by the Apostle Paul, reveals the Open Secret of the gospel — that Jesus’ death and resurrection (the secret) have joined together two unlikely peoples (the opening), Jews and Gentiles. Ultimately, Newbigin’s missiology is rooted in the cross, what Newbigin describes as “the place where God reaches all the way to the left and right to embrace the world, and all the way up to heaven and all the way down to hell.” – Josh Gritter

The Romance of the Word: One Man’s Love Affair with Theology (1995), by Robert Farrar Capon: I am, by no means, an academic. As if under a spell, I fall asleep immediately whenever anyone mentions the word homoousios. Seminary was nice in theory but hard in practice, something completed only by piggybacking on the necks of my more intellectual friends and colleagues. Thankfully, for people like me, there is Robert Capon. This cigar-smoking, brandy-enjoying priest and renowned food critic was, according to himself, “a cook, a woodworker, a runner of the roads, and reasonably competent linguist, administrator, canonist, and musician — but not the kind of reader a theologian is usually supposed to be.” And yet, I have learned more about theodicy, homiletics, and hermeneutics from this man than I have just about anywhere else. He is not only a joy to read, but his feet are firmly on the ground of real, everyday life. The New York Times Book Review once wrote, “Theology [Capon] says, is a word game, the most serious word game of all, and he plays it very well indeed.” This collection of three different books (An Offering of Uncles, The Third Peacock, and Hunting the Divine Fox) provides a conversational, comedic, and concrete approach to the Christian faith that is desperately needed for those who love to talk about Jesus but prefer modern English to ancient Greek. – Sam Bush

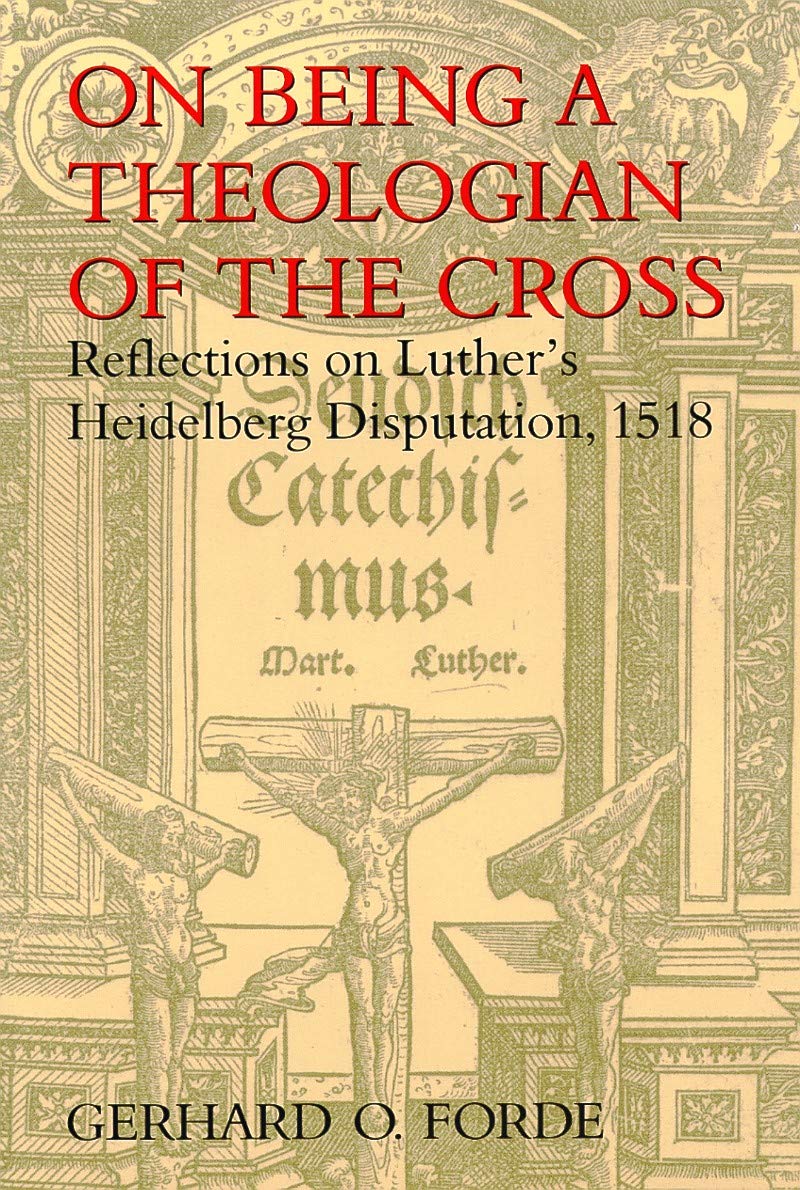

On Being a Theologian of the Cross (1997), by Gerhard Forde: I was introduced to this book by a Lutheran pastor/friend of mine. I don’t think he was secretly trying to convert me away from my noncreedal tradition, simply sharing Forde’s book about how we are saved by grace through faith. Built as a commentary on Luther’s Heidelberg Catechism, Forde distills the gospel as a salve against glory-based theologies that turn a bad thing good and a good thing bad. There is challenge in their pages, but that is par for the course of those with a bound will. But for those with the ears to hear, you’ll receive those comforting gospel words again and again and again. More often than not, I have to convince myself NOT to quote him in each week’s sermon. – Will Ryan

Systematic Theology: Volume 1: The Triune God (1997), by Robert Jenson: Esoteric. The opening pages of this work make it clear that Jenson has given considerable thought to the Trinity. Jenson doesn’t start at the start. He starts in the pulsing heart of theology, proclamation. I’ve never read a book that so quietly affected me. I would often set the book down and start working on my sermon — and I can think of no better recommendation than that. – Ryan Cosgrove

Christian Hope and Christian Life: Raids on the Inarticulate (2001), by Rowan Greer: “The good news must be a promise before it can become a moral demand,” writes former Yale patristics scholar and Anglican priest Rowan Greer. A faith focused exclusively on fixing the here-and-now, he argues, neglects the tragic dimension of human life, abandons eschatological hope, and reduces Christian life to a kind of moralism supplanting the message of salvation. Greer’s “raids on the inarticulate” (a phrase borrowed from T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets) reclaim the hope of Gregory of Nyssa and Jeremy Taylor, for whom it is “a heavenly and eternal reality in which the believer may participate,” and of Augustine and John Donne, who understand the Christian life as one lived in anticipation of that reality. “The difference between despair and hope is the difference between a problem and a mystery,” wrote 20th-century Christian philosopher Gabriel Marcel. Greer doesn’t solve a problem. He enriches a mystery. – Ken Wilson

Practice Resurrection: A Conversation on Growing Up in Christ (2001), by Eugene H. Peterson is a long conversation. I felt like I was going on walks with Eugene while reading this. He was Tychicus at the end of Ephesians who “told me everything.” And now, I am Tychicus too. Sometimes we would stop, and I would ruminate on a particular thought — “A friend suggested this to me: ‘Do you think that the empty tomb of the Resurrection is an echo of the empty Mercy Seat of the Ark? That the two angels ‘in dazzling clothes’ (Luke 24:4) who gave witness to the empty tomb as evidence of resurrection might be an allusion to the two cherubim marking the emptiness that is fullness at the Ark?’” WHAT. He does this all throughout the book. I feel like he’s winking at the reader. Which makes me just smile and shake my head in wonder and thank God for his abundant richness that we get to take part in. – Janell Downing

Grace in Practice: A Theology of Everyday Life (2007), by Paul F. M. Zahl: The influence of this book is difficult to overstate, as many of its trademark theological phrases have become common parlance: one-way love, high Christology, low anthropology, and the un-free will. But more than slogans, the book’s unparalleled strength is how thoroughly the idea of grace is exhaustively applied to everyday life. Grace with little children, in singleness, in marriage, in politics, in criminal justice, and in pastoral care … the list goes on. Sometimes dismissed by detractors as a perverse “radical grace,” the consistency of thought on display instead reveals how often we turn to different gospels (Gal 1:6) to answer life’s many questions. – Todd Brewer

The Crucifixion (2015), by Fleming Rutledge: I bought this book during COVID because … well, what else was there to do? Now I return to it and my highlighted passages every Lent. It totally changed the way I see the cross and, really, my entire understanding of this central tenet to my faith and the sacrifice made on my behalf — the depth of which I had never come close to grasping before. – Stephanie Phillips

Loved and Sent: How Two Words Define Who You Are and Why You Matter (2016), by Jeff Cloeter: This book is grace from beginning to end. It gets down to the core of what it means to be a Christian in a very non-preachy and relatable way. It makes a great book study for churches. What I love is that it has deep and thought-provoking content while also being enjoyable to read. – Juliette Alvey

Holding Faith: A Practical Introduction to Christian Doctrine (2018), by Cynthia L. Rigby: A rare, accessible introduction to Christian doctrine. It’s a book I return to often, full of underlined and highlighted pages. I appreciate how Rigby brings major theologians from across time and traditions into conversation with one another, Scripture, pop culture, and lived faith. This book goes beyond simply defining doctrine by asking “So what?” after each doctrine is introduced, expanding faith and understanding. – Kallie Pitcock

The Sound of Life’s Unspeakable Beauty (2020), by Martin Schleske: This book opens with Psalm 96:12, “Let all the trees of the forest sing for joy,” and a quote from the painter Friedensreich Hundertwasser: “We have lost the ability to create metaphors for life. We have lost the ability to give shape to things, to recognize the events around us and in us, let alone to interpret them. In this way we have ceased being the likenesses of God, and our existence is unjustified. We are, in fact, dead …We feed on knowledge which has long since decayed.” Martin Schleske is a luthier. Through his profound knowledge and experience of making violins, he creates a theology that is beautifully intimate and awe-inspiring, pointing us all to the One for whom our soul sings. – Janell Downing

Churches and the Crisis of Decline: A Hopeful, Practical Ecclesiology for a Secular Age (2022), by Andrew Root: When I read this book in 2022, it significantly changed how I view congregational renewal. Instead of looking for ways to “hack the system” to stop church decline, Root opens us up to the shocking belief that the church is not the central player in the story. Instead, communities of faith are called to sit and “wait on God,” looking to see where God is active and join in. In many ways it is the congregational version of Gerhard Forde’s On Being a Theologian of the Cross in that the church isn’t engaged in trying to justify itself, but seeing God at work in the world and in our own lives. – Dennis Sanders

Excellent choices! The only disappointment is that there were no Jürgen Moltmann books. A theological hero of mine. A theologian who I think would fit well within the Mockingbird collective.

No Hauerwas?

Great list, but nothing by N. T. Wright?

For what it’s worth, I love Surprised by Hope so far, but I have not yet finished it :).

It would not be self-serving to have at least one book by Paul F. M. Zahl on the list.

We do! Grace in Practice…