Update: Given the level of interest and feeling this post has garnered since it was initially published, readers are encouraged to take a look at the two follow-up pieces. Click here for the first, and here for the second.

To be honest, I didn’t even know Thomas Kinkade was dead. That was until I read this fascinating piece on Kinkade, America’s favorite sentimental “Painter of Light,” from The Daily Beast by Zac Bissonnette: “The Drunken Downfall of Evangelical America’s Favorite Painter.” I also had no idea Kinkade was (a) an Evangelical Christian and (b) an alcoholic. The story is at once alarming, yet not surprising, and ultimately really sad. Thus, I can’t help but explore it here.

(Before I move on, I should preface this essay by noting that Kinkade died on Good Friday two years ago, so I was probably distracted by the busyness of Holy Week to catch the news. Apparently missing this story also means I managed to miss our friend Dan Siedell’s must-read article shortly following Kinkade’s death. Anything I write here is a mere shadow compared to Siedell’s artistic expertise and poignant interpretations.)

This is a mugshot, by the way.

I know Kinkade from kitschy tourist sections of the California towns where I grew up. One could always find his shops on beaches or on historic Main Streets selling prints of his disturbingly idyllic work. Even as a child I got a strange vibe from his shops. If I were to judge the man solely from his paintings, I would have guessed he was more like Bob Ross and less like Keith Richards. Although he painted like Ross, he certainly partied like Richards. It is too bad he never hit the kind of rock bottom that leads to recovery. Rather, he bottomed out in death due to “acute ethanol and diazepam intoxication”—alcohol and Valium. He OD’ed.

Personally, never have I been more interested in Thomas Kinkade. Here is an interesting tidbit from Bissonnette’s article on the inspiration and thought process behind his work:

In the 1980s, Kinkade thought the art world had become detached from the public—and he saw himself as the person to return it to an artist-as-servant model, where painters affirmed rather than challenged social values. His hero was Andy Warhol, who, he felt, had rescued art from insularity and infused it with iconography that meant something to ordinary people; what Warhol did with soup cans and Marilyn Monroe, Kinkade thought he could do with Eden-inspired garden scenes and Cotswolds cottages.

But the story continues that despite painting a world unmarred by the Fall at Eden, Kinkade spiraled increasingly out of control into a debauched life of sin contradictory to his conservative Evangelical values. Eventually, his surprising private behavior became public.

The company persevered, but Kinkade himself did not fare as well. He controlled his fondness for alcohol and strip clubs adequately when his wife was with him, but things spiraled out of control when he was on the road. By the mid-2000s, Kinkade’s family was pushing him into inpatient rehab as stories about his alcoholism started to make the news. The last five years of his life were characterized by the pattern of ups and downs familiar to many addicts.

“Thom believed that he should be able to control it, and that contributed to his downfall,” his brother remembers. “He had six months of sobriety and he was doing all these wonderful things. He was calling me and telling me: ‘Feeling good! Losing weight! Doing great!’ And then suddenly, you get a message: ‘Thom’s had a beer.’ Two days later, he’s into vodka. Seven days later, [he’s] dead.”

It is the sort of recidivistic tale that is all too familiar. Knowing so many who struggle with alcoholism, I can’t help but feel for Kinkade. Since his death, Kinkade’s brother Patrick has become the spokesperson for the Kinkade brand, and he touches on the tragedy when giving retrospectives on his brother’s career. There is a glaring problem in Patrick’s thinking though that runs deep in much of Evangelicalism:

“My brother was a good man,” he said, pausing as he choked up along with much of the mostly middle-aged and older audience. “The tragedy of my brother is he eventually fell to his own humanity. The triumph of my brother is that his art was never touched by that tragedy. His art was affirmation that there was hope, there was beauty, and a statement of love that wasn’t touched by this.”

Those last two sentences make my heart sink. The dilemma with Kinkade’s art is that he sweeps human suffering under the rug. It sees the world through a pre-Fall lens. His paintings are a big fat lie. And I have to wonder if the dishonesty actually contributed to his personal suffering more than it helped. In other words: What would have happened if Kinkade had struggled with his pain in his art rather than painting a facade over the human predicament?

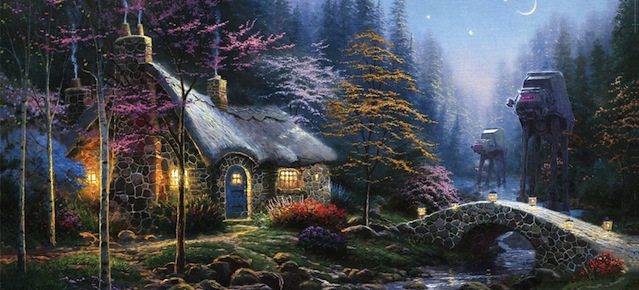

About a year ago a guy named Jeff Bennett created a hilariously awesome series called “Wars on Kinkade” that totally corrupted Kinkade pieces by introducing battle scenes from Star Wars into the bucolic scenes. The series is of course so worthy because it exposes the problematic facade Kinkade built. Bennett’s alterations introduce original sin into the equation. This is a good thing not because sin is good. Rather, sin is real, and art ought to grapple with sin rather than avoid it.

Chances are though, hypothetical Kinkade paintings that came from a place of suffering never would have sold millions like the real Kinkades did (and still do). As his brother Patrick says in a quote that ends Bissonnette’s article, “His legacy in terms of new publications … will far outlive anybody who reads this article.” Unfortunately, this is because, like Kinkade, the masses, including far too many Christians, like having the wool pulled over their eyes. Give me Hallmark, Kinkade, Joel Osteen, and Chicken Soup for the Soul they seem to say. They want the stuff that is never touched by tragedy, but ignoring the pain is no triumph. Rather, as Siedell says in his treatment of Kinkade:

Kinkade’s work is the meticulously painted smile on the Joker’s disfigured face. It refuses to deal with the fallenness, brokenness, sinfulness of the world. And more troubling, it enables his clientele to escape into an imaginary world where things can be pretty good, as long as we have our faith, our family values, and a visual imagery that re-affirms all this at the office and at home. That Kinkade and his followers believe this to be “Christian art” is an affront to art.

As a Christian with with evangelical—small e—leanings myself, I am finally most saddened by Kinkade’s story because I know Evangelicalism helped him perpetuate his lie. Christians often want to ignore the darkness and sin. But I, for one, find consolation in art that explores the dark places with honesty. It strikes a chord, showing me I’m not alone. It’s counter-intuitive perhaps, but such art gives me hope and often helps me to heal. I wish Kinkade could have gone there, too. He didn’t, but there is a place for honest art created by and/or appreciated by Christians. For now maybe Kinkade’s life story can serve as something of a cautionary tale about what happens when Christians demand just the “clean” stuff. We might instead be surprised to find more comfort in artists who bear their Cross and create from a place of suffering.

Epic bonus video: Kinkade maps Easter onto Good Friday.

http://youtu.be/XOtp1T-hUD8&w

COMMENTS

25 responses to “The Drunken Downfall (and Death) of Thomas Kinkade”

Great Article, Matt. I had no idea about Kinkade’s personal life and death either. Its probably safe to assume he didn’t often hear the “good news” in all its goodness.

I wonder, however, if we could also see his art as his expression of the hope within him. His Christian hope. In the same way that many artists create beauty while struggling with ugliness in their own lives, maybe Kinkade wasn’t perpetuating a lie but an (inspired?) vision of heaven which contrasted with the blackness in his heart.

The truth is, I learned to hate Kinkade’s “art” a long time ago as my more creative friends declared Kinkade an impostor to true art. In retrospect, I wonder if I was too harsh. I do remember being inspired as a 12 year old seeing a Kinkade print on my uncle’s wall.

Great insights! I have a lot of sympathy for the poor man, who is a ready-made sermon illustration for those of many different theological leanings. On the other hand, it is ironic that a man so devoted to creating an art devoid of irony should end up as one of the most ironic illustrations of the unavoidable fact that any life, and most of all any Christian life, is full of irony. Now there I go, making him into my own sermon illustration!!!

It’s only fair to Thom that you try to know his background better before writing an article about him. Couldn’t help but hear a self-righteous tone and I am surmising you aren’t middle aged or older.

Hi Kathy – I hear ya. However, after getting to know Dan Siedell (who Matt rightly cites) and having gone personally on three of Dan’s guided art museum tours, I have to say that Matt’s “tone” is well informed.

Siedell (an art museum curator and doctorate in art history) suggests that the best art captures the “ultimate in light of the pen-ultimate”. Matt is suggesting that Kinkade does not distinguish between the two, and leads the observer to believe that perhaps the best this life has to offer is “a nice little house in the country” – void of the pain, sin, agony, love, fury, strife, and connection present in the “actual” human experience.

To your valid point, art is in the eye of the viewer. Matt and Siedell would just say that the degree of substance and depth beheld by the viewer is in direct proportion to the (oft critically acclaimed or denounced) quality of the art.

Thanks for the post Matt, awesome. I appreciate the thoughts on the paintings (and trials) of TK both from the perspective that it represented an ideal of Christian life that is elevated above suffering, but at the same time also as Josh commented above, that such a saturated view of prettiness could be an expression of hope that is not necessarily the empty ‘best life now’. Perhaps his personal story provides the backdrop that helps the paintings represent that hope that we can imagine he longed for as we all do. But I do agree that the paintings lack that kind of depth entirely.

I know people who have been attracted to his paintings for what I would call the wrong reason (everything with God comes up roses). And while I personally find the paintings completely uninteresting as paintings, I also weary quickly with art that dispenses with visual poetry and craft in its effort to be relevant and meaningful.

While his paintings fell short for me, the Jeff Bennett take on them did too…I need something more than either of those Isn’t there always a tension between what is beautiful and hoped for and what is suffered and lived through? I too also find healing in dark places…blues music confronts my disappointments and heals them at the same time. But the music still needs to be beautiful as blues music and the musician still needs to know his craft. If that is not there, it is a death without a resurrection for me and that is also not reality (I hope).

Josh, Michael, Kathy, Howie, & mbab: Thanks for your insights. More than anything, I hoped this post what spark some thinking/response/discussion, and not the definitive word on Kinkade–I recommend Siedell’s pieces for something more thorough. And if a self-righteous tone came across, I’m disappointed because I was actually trying to express my genuine sadness for Thomas-Kinkade-the-man since he never seemed to mix beauty with pain on his color palette–I’m convinced that exploring his own suffering and the human condition more generally might actually have saved his life.

Someone I should have mentioned in this post to provide the type of balance Josh and mbab are looking for is the former football player Todd Marinovich, who had a very difficult childhood, which led drug addictions, and a very public downfall (all like Kinkade). After hitting absolute rock bottom, Marinovich’s art blossomed, and it has helped him in his recovery. Although his work might not be everyone’s taste, it does at least touch on both the ugly and the beautiful/hopeful. As a consumer/appreciator, I’d personally much rather have a Marinovich than a Kinkade hanging on my walls: http://toddmarinovich.com. And as a creative person, I can’t help but produce work that is more akin to the beautiful-ugliness that he produces.

Believe me, I need hope more than anyone. But I can’t get to Easter by skipping Good Friday, Holy Saturday, and the reality of my personal suffering and the suffering of those around me. Watch that video, and you see an artist who, as Siedell explains, paints a smile and the ugly face of the Cross. And he even told us his aim was to do so when he explained that his method in his entire body of work was to paint the world without the Fall. It’s one thing to do something like that in one painting or a set of paints, but Kinkade spent his life creating an entire world I can’t relate to. The saddest element of that video though is that so many people (sincere Christians!) seem to being eating up what he serves them.

Thanks for an interesting article Matt & for the additional views and comments of those posted here. I did not realize he’d passed away, and think part of the relating to the artist is generational, as in many people my parents age seemed drawn to his style.

I’d add one other perspective. While art in painting or other forms like my interest in photography may only capture a moment, does it necessarily have to include the realities of both pain and beauty? The Bible explains “they are without excuse” when it talks only of the wonder and beauty of creation pointing to our Creator, Father, God. It’s the Spirit who convicts of sin, righteousness and the judgement to come, and perhaps that might include confirming why we have addictions, injustice, pain or suffering.

If Kinkade wanted to only portray pre Eden like images, the flaw is not in the captured moment, but the context or thoughts that follow. If I’m understanding your criticism, it would be equally valid to be criitical of art only focused on capturing the moment of evil, pain or suffering. If I take a photo of a beautiful flower and pair it with a verse about how God’s Word lasts forever, then I don’t think it’s dishonest or not portraying reality to not show the flower withered. It just captured the moment, had a context and wasn’t intended to address all of reality.

Your point is valid when we discuss individual works but it breaks down, I think, in the face of an entire corpus of work which tries to deny death by turning back the clock rather than anticipating the eschaton.

I don’t know if we need you explain to us why we don’t want a Thomas Kinkade hanging on our wall. I mean, I’m 30 and I grew up looking at these paintings a grandma paintings. These were to be enjoyed by grandmas across the USA. What person reading Mockingbird would actually need someone to say “whoa, I used to like Thomas Kinkade, but now I see how phony his paintings are.”

Overall, I like this article up until halfway down when you get a bit self-righteous about Kinkade in commenting on his brother’s comment:

“Those last two sentences make my heart sink. The dilemma with Kinkade’s art is that he sweeps human suffering under the rug. It sees the world through a pre-Fall lens. His paintings are a big fat lie.”

My question is—–is his brother trying to sell his brand——or is his brother trying to find some meaning in his brother’s death? I hear a grieving brother. He’s a family member, so I assume he’s ashamed as much as he is a advertiser. Along with that, while while Kindade’s art was cheesy and worst of all attached a Bible verse to it, it would be like a pre-Eden fantasy. Isn’t that a half truth rather than “a big fat lie?”

Thanks for giving commentary on Kinkade. I didn’t know he died of an overdose. But lay easy on the snark.

Perhaps I am another of the misguided observers of Kinkade’s life, but it occurs to me that what Kinkade painted was the Eden that God created for us. It is the life that we all desire to have because that is the way God created us, with the perfect job, perfect life, and interesting things to do all day. It is the reason we fall also, by the way. We try to fill these needs in counterfeit ways, through work, addictions, comparisons, judgmentalism…even religious efforts, rather than to depend on the counter-intuitive path of looking at the world through Jesus’ eyes.

On the one hand his work was the Pollyanna view of life, that there is something good in everything. That view is what is detested by those of us who recognize the damaging fallout of such a view. But on the other hand his work depicts those things that Christ died to redeem.

Tragically Kinkade’s life can be seen both ways as well.

“il faut souffrir pour etre belle” Any art that does not somehow reflect this tension very quickly veers from the “beautiful” and toward the inane and soporific. Of course, sometimes I enjoy things that are inane and soporific.

Thomas Kinkade was a good artist. He depicted light well. Nature was his shtick (just not funny), with a lack of creatures, mostly flowers and buildings and skies and oceans… a cross too. How to relate? Maybe I catch a glimpse here and there in a sunset or pretty flowers, but he presents more like a Deist, than a Christian with his fantasy-like images of nature. I am reminded of Norman Rockwell from the 20’s, who painted some idealistic scenes, yet he dealt with human interaction, including controversial ones: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Problem_We_All_Live_With Norman Rockwell expressed human suffering and emotion through his art, and Thomas Kinkade continually expressed something like, ‘Hey, this cross looks pretty with a river in the background and some light, don’t ya think?’ Well, yes, but, Jesus was nailed to wood at the “Place of the Skull” (Golgotha), outside the camp, with two notorious convicts “one on either side” (John 19:18). And Thomas Kinkade was suffering with a nasty addiction that killed him. No one seemed to know. He just seemed like a good guy who painted pretty things – Nothing bearing of any fault, only perfection. An imaginary earth, yes. Not an earth currently groaning with the reality of human suffering as we all know it. And if there was suffering in the American 20’s, as depicted by Norman Rockwell, that was cause for bits of expression, relation, a faint crying out, then there is suffering in America 2014 (sporadic and hidden) that is cause for the same. Given his secret suffering, it is a conundrum that he did not acknowledge suffering in his art. Maybe he wanted to pretend he was not suffering while living in his fantasy world…

The hope of humanity is found in the cross, it is the cross of Christ and “him crucified” in light of broken humanity. The hope of scripture goes hand-in-hand with suffering: Christs’ which leads to hope in our suffering.

I close my eyes and think of America today. I hear us say, ‘Admit it!’ Then I see us look into the eyes of Jesus as he looks back..as if we were Judas Iscariot. But instead of killing ourselves, we say, “I have been crucified with Christ; it is no longer I who live, but Christ lives in me; and the life which I now live in the flesh I live by faith in the son of God, who loved me and gave himself for me” (Galatians 2:20). Amen.

As a recovering addict I have a different take on it. He painted the longing we all feel inside for the true and beautiful, life as we hope it could be. The inner life of those who are in the thrall of alcohol or drugs is filled with gritty, ugly, and hopeless visions. This was his escape and testament to what he hoped would await him when he died. We can all sit back and critique his art as an inaccurate portrayal of the ‘real world.’ but I think that misses what he was trying to do.

I think you might appreciate Simcha Fischer’s (www. ncregister.com /blog/simcha-fisher/whats-so-bad-about-thomas-kinkade) take on Kinkade’s work, which in some ways comes at it from a similar angle (she’s also linked it to another article from First Things which tackles Kinkade’s use of sentimentalism. It’s a shame the pictures aren’t visible anymore, but I’m sure you could find them elsewhere online if you wanted to look them up).

Not to judge the artist, but such art for me encapsulates so much of what I find frustrating with contemporary Christian media, which seems to have wholly swallowed the equation of Christian aesthetics or ethics, with a rather shallow, respectability politic. There is something anti-incarnational, a kind of works righteousness. But then, I guess that’s what a traditionalist hipster would say!

The only thing that jumps out at me that has not been stated is the similar trajectories between Kinkade’s art and the craftsmenship of the Old Testament holy objects. Many of the constructions in the Old Testament (the Ark of the Covenant, the temple, etc.) contained pre-fall, creation-centered imagery. When Old Testament Israel worshipped, it was as if they were remembering Eden and the union with God His people once enjoyed. This is what Kinkade was portraying in his paintings. Yet we all know this fixation did not end well for Israel. They eventually sought fulfillment from the pleasures of this world including false deities and God let them be consumed by their foolish pursuits. Hauntingly similar, is Kinkade’s tragic end.

We all long for the perfect union with God in the untainted world for which we were created. However, a fixation on this perfect past will blind us from the beauty of God in the present and how He is bringing us into His future. The beauty of Eden was never in the untainted trees or in the absence of sin, pain, and struggle. It was in the presence of God. We have this same presence now as the Holy Spirit dwells in the church. (By church I mean the messy wayward people, not the pretty stained glass buildings.) It is the absence of this recognition of God’s current presence whether in paradise or in struggle that is true tragedy.

“They want the stuff that is never touched by tragedy, but ignoring the pain is no triumph.” !!! Loved this Matt. Thanks!

What is one man’s junk is another man’s treasure. Art indeed is in the eye of the beholder not the artist. If an artist rendering of anything brings inspiration of any kind to anyone, it is art. It does not need to have some pseudo-intellectual deep meaning for all.

Very helpful in understanding why these paintings are not great art, (rather they’re very bad!) and why they appeal to so many people. Very sad that he died the way he did.

Am I the only one who appreciates art for the picture and how well it is recreated with a paint brush; not a theological lesson. The saying is “Beauty is in the E,YE of the beholder, not the brain!

I was reading my Bible this morning then I thought what about this Kinkade guy with this beautifull wife ;with a great testimony . The Bible “The reflections from the heart of God” is so beautifull because of his paintings .I decided to look up for more.His story is sad but I also think it exposes many of our christian styles of living .It is a lesson too .

To be honest, I didn’t even know Thomas Kinkade was dead.

So glad you clarified that question of your honesty. At least I hope you are telling the truth.

Darkness is clearly evident in much of Kinkade’s work; you are simply not looking closely enough. Try going a little farther back in technique than the late 20th century memes you are not seeing.