I am the son, the grandson, the nephew, and the cousin of alcoholics. I am not, however, an alcoholic. I have felt disgust towards alcohol since adolescence and for most of my adult life because of my close familiarity with its misuse. But I have been unwell in a different, though related, way: I have attempted, spectacularly without success, to appease or to scold people away from bad decisions, have acted my part in bargains that others have no idea they made with me, and overall tried to keep life chugging along by either taking on more than I ought to or by trying to Death Star the inevitable impediments that get in its way. My addiction hasn’t been to substances: it’s been to staving off disappointment and abandonment.

I began attending Al-Anon — a 12 step program for children and loved ones of alcoholics — just before Covid struck the U.S. The most difficult and most frightening thing I’ve had to confront thus far in Al-Anon is a twinned truth: that I didn’t cause alcoholism, and that I can’t cure it. While on some level I knew the first, in some deeper part of myself I must not have believed it, as I invested all of my being into the project of the second half. For years it was terrifying to admit my powerlessness because the unspoken suspicion was that such an admission would be submitted as evidence that I’m effectively worthless. Who knows where this fear came from, but it has been real and it has been petrifying. So for the longest time I did everything I could to convince myself that I could, in fact, defeat it and every other addiction and vice that threatened those I loved. But I couldn’t.

The painful part of confronting this truth is coming to accept how things are. That is, not trying to fool myself that these painful things are figments of my imagination, conceding that these things have happened, that my loved ones have done these things, and that, because they have been a prey to this demonic power, can be counted on to behave this way. But I could not do this without learning that acceptance is not approval. This has been the single hardest thing to internalize. Not only to believe, but to absorb into the reciprocal interface between my body’s muscle memory and the go-to neural pathways that immediately process hurt and disappointment. It’s so immediate, that feeling that I am giving this or that behavior my approval whenever I opt not to verbally eviscerate someone that has lied to me or prioritized me after a substance. I don’t initiate it or permit its progression: it occurs as organically and unthinkingly as breathing.

In fits and starts I have had to recognize that some things are not for me to fix. As much as I want to make this — this relational dynamic, this history, this pattern of unreliability, this pain — better, it’s beyond my ability. When there’s reasonable action that can be taken, I can take it. And when there is nothing I can do I must entrust it to God, who often moves at a frustratingly different speed than I would prefer. Opting to trust doesn’t automatically engender patience; such a thing only accumulates slowly. A phrase I heard in Al-Anon gives me some consolation: “Guide me in all I do to remember that waiting is the answer to some of my prayers.”

But that consolation arises because I am confident that a specific higher power is listening to and concerned with my prayers. The program’s lack of concrete articulation of who he is has been off-putting to me because it sounds so wishy-washy. As though thinking the word, “God,” makes what you imagine real. So Aaron Weiss: “I said ‘water’ expecting the word would satisfy my thirst.”

And yet … there are people who arrive at a point where what they are accustomed to comes up so dramatically short that long ignored or repressed, fundamental truths about human existence become nigh undeniable. And in that recognition a surrendering of that which we naively call “control” is made, relinquished to a power greater than themselves, a power outside the realm of mundane competition, status-seeking, and pleasure-hoarding: outside of what we tend to consider possible.

It seems to me that this is only possible because this program trains individuals to renounce their frantic attempts to be their own lord. This program routinely de-gods human beings. A radical humbling occurs in every participant who submits themselves to its disciplines, finding themselves decentered from the attempt at self-rule. It’s a pertinent question to ask if it routinely, explicitly directs participants to the God Who Is and Was and Is to Come. Though the answer is “no,” it must be said that that same God is the One who unfastens the burdens which keep people enslaved to such pointless repetitions and impossible power grabs which both disappoint and degrade the one so trapped. If God is at work in the program, then I have to think he is very gracious to not requiring the full confession of who he is prior to his so working.

Blaise Pascal wrote in Penseé 250, “The external must be joined to the internal to obtain anything from God, that is to say, we must kneel, pray with the lips, etc., in order that proud man, who would not submit himself to God, may be now subject to the creature. To expect help from these externals is superstition; to refuse to join them to the internal is pride.” Contrary to our common expectations, we should not wait to kneel in prayer until we have believed: we should kneel instead, and in praying, we will believe. Often the force which keeps us bound within the gravity wells of stultifying habits, neuroses, and maladaptive customs is our unwillingness to act so as to believe.

Practices shape us just as arguments do, but not in the same way: practices have their own persuasive power, nudging us toward the accomplishment of a thing. The proof that most determines our action is that is which given in doing, in the taste of that food or drink, in the relief of confession, in the cathartic release of music, the comfort of a loved one’s embrace.

“It is not enough to believe only by force of conviction,” Pascal elaborates in Penseé 252, “when the automaton [the part of us that is automatic and not ruled by the intellect] is inclined to believe the contrary. Both our parts must be made to believe, the mind by reasons which it is sufficient to have seen once in a lifetime, and the automaton by custom, and by not allowing it to incline to the contrary.”

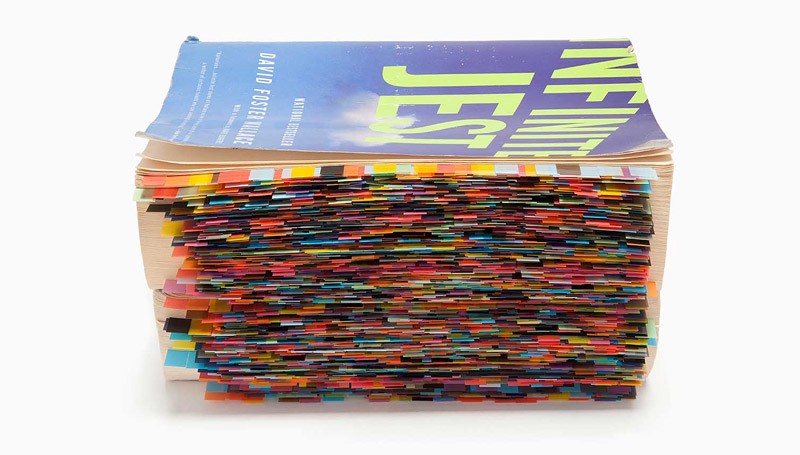

David Foster Wallace depicts this beautifully in Infinite Jest. Earlier in the novel (a novel so big, mind you, that page 200 is “early” in it), as Wallace is describing the halfway house where much of the novel takes place, he introduces the reader to wisdom they might only learn by being admitted into such a place. One of them being that “AA and NA and CA’s ‘God’ does not apparently require that you believe in Him/Her/It before He/She/It will help you” (201).

Don Gately, an addict, feels like a hypocrite going through the motions of gratitude and prayer every morning and evening but his sponsor informs him that, “it didn’t matter at this point what he thought or believed or even said. All that mattered was what he did. If he did the right things, and kept doing them for long enough, what Gately thought and believed would magically change. Even what he said” (466).

Gately, of course, protests. He doesn’t understand how that could possibly be so. And if he can’t understand how that effect can follow then the effect cannot possibly follow. Right?

A counselor presents Gately with the analogy of being handed a box of Betty Crocker Cake Mix. Gately wonders what this could possibly have to do with beating an addiction and the counselor lovingly tells him to give his intellect a break and for once shut up and follow the directions. Wallace (in his characteristically coarse vocabulary) writes:

It didn’t matter one fuckola whether Gately like believed a cake would result, or whether he understood the like fucking baking-chemistry of how a cake would result: if he just followed the motherfucking directions, and had sense enough to get help from slightly more experienced bakers to keep from fucking the directions up if he got confused somehow, but basically the point was if he just followed the childish directions, a cake would result. He’d have his cake (467).

So Gately carries on with praying, asking God-as-he-understood-him to remove the desire for substances and giving thanks for days without substance use. He is shocked one day on his way to work to realize that he has not thought about, much less craved, substances or looked to escape life by getting high. But this confuses him all the more. “How could some kind of Higher Power he didn’t believe in magically let him out of the cage when Gately had been a total hypocrite in even asking something he didn’t believe in to let him out of a cage he had like zero hope of ever being let out of?” It frustrates and mystifies him so much that he cracks a tabletop literally banging his head against it. An old AA veteran named Ferocious Francis hears Gately out, and when Gately asserts that there’s no a way a God he doesn’t understand enough to believe in would nevertheless help him escape his cage Francis suggests that “maybe anything minor-league enough for Don Gately to understand probably wasn’t going to be major-league enough to save Gately’s addled ass” (468).

God does care that you believe in him, that you know him as the One he is, but Wallace is right: the extent to which you believe or the quality of your belief is not a prerequisite for God’s coming to your aid. He isn’t waiting for the right confessional password to put deliverance into action. This is the One, after all, who came to the first disciples as a Lord-of-their-understanding, who patiently endured the long process of refining their misconceptions and correcting what they “knew” such that after rising from the tomb it could be properly confessed, “My Lord and my God!” (Jn 20:28). Seek him, then, and he will be there as he is the One who persuaded you to seek him in the first place.

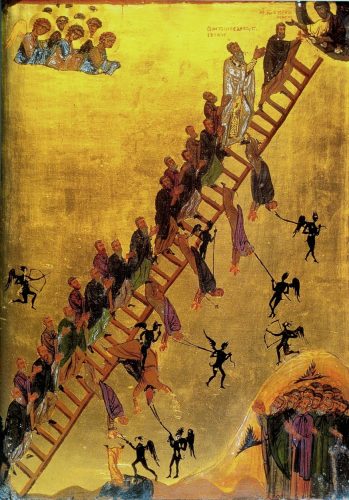

God is too often pictured waiting atop a ladder, waiting to receive human beings who improve so as to ascend to him. The ladder image has a long pedigree in Christian thought, receiving systematic portrayals by Benedict of Nursia and John Climacus. These have been and can still be helpful, but the image is woefully misunderstood if God is imagined as aloof, simply waiting for us to get our act together to join him where he is. This is simply un-Christian. The good news of this God is that the initiative is all his, that he seeks us long before we ever seek him, that we come to love him because he first loved us. If there is truth to the ladder image, then it is that God himself is the ladder. Jesus is the way, that is, the connective passage between earth and heaven, as John’s Gospel again illustrates. For when the skeptical Nathanael acclaims Jesus as the Son of God, Jesus tells him he’s only scratched the surface. Drawing upon Jacob’s dream of a stairway to Heaven, Jesus asserts that he and the other disciples will see more magnificent things, even “the angels of God ascending and descending” on him (Jn 1:50-51). The stairway Jacob saw is Jesus.

Despite what some might say, faith is not opposed to action, but conducive to it. Alcoholics Anonymous shows what is lacking when believing and doing are separated in such a way that pure activity and pure passivity are the only possible possibilities of Christian existence. Either alternative still keeps the focus upon the addled sufferer rather than the One who can deliver us. The “faith” that would dismiss all doing as “works” sits there, pleased with its pious complacency. As soul and body belong together, so do faith and doing. Better to be on your knees than on your butt, proud of having done nothing.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply