Of all the reversals we’ve seen take place in our culture of late, one of the most unexpected has to be what’s happened with “nerds”. If you had told me in 1988 that the group of oddballs who sold me and my friends our comic books every Saturday would come to dominate the mainstream, part of me would’ve wanted to believe you, but wouldn’t have.

Back then, “nerd” was a label to be avoided not embraced. It wasn’t a synonym for shy or misunderstood or even studious as it is today (though those traits often fell under its umbrella). Nor was it a term to describe people with eccentric interests. Tons of ‘jocks’ read comic books, watched sci-fi films, and played video games. “Nerd” referred primarily to a mix of social awkwardness and know-it-all-ishness, which, regardless of how much compassion you had for the insecurity and intellect that may have lied at the root, was pretty insufferable. Indeed, one of the hallmarks of nerd culture was the way it valued being right over being relational. These were not just guys who liked the X-Men, in other words, these were the guys who would correct you when you mixed up characters. Think Billy Mitchell in King of Kong.

I say “guys” because I don’t recall the word ever being used to refer to a girl. (There were other words for them). To be a nerd, at least in middle and high school in the 80s/90s, meant you were sequestered from pretty much all non-maternal female contact. Not by choice. Ironically enough, female perception tended to be a much more reliable indicator of “nerd-dom” than male perception. If girls liked you liked you, you weren’t a nerd and vice versa. (Bryan wrote a couple years ago about the not-so-hidden misogyny this bred in nerd culture–where women were seen as prizes to be won rather than people to get to know. Pedestal city!).

I say “guys” because I don’t recall the word ever being used to refer to a girl. (There were other words for them). To be a nerd, at least in middle and high school in the 80s/90s, meant you were sequestered from pretty much all non-maternal female contact. Not by choice. Ironically enough, female perception tended to be a much more reliable indicator of “nerd-dom” than male perception. If girls liked you liked you, you weren’t a nerd and vice versa. (Bryan wrote a couple years ago about the not-so-hidden misogyny this bred in nerd culture–where women were seen as prizes to be won rather than people to get to know. Pedestal city!).

Attempts to romanticize nerds popped up on the big screen as the nerds in question grew up and began to write and direct their own films. Weird Science, Real Genius, Revenge of the Nerds, Back to the Future–long before The Big Bang Theory was a gleam in Chuck Lorre’s eye, these sleepover stand-bys sowed the seeds of the Great Nerd Rehabilitation. As much as I love them, they tend to be juvenile empowerment fantasies, i.e. slightly more prosaic versions of the Spiderman myth. Jocks get their comeuppance. Cheerleaders repent of their shallow ways. The balance of power shifts in the direction of the marginalized. Now it’s their turn at the wheel.

Well, the San Diego Comic-Con has just passed, and it would appear that fantasy has truly become reality. Social mores have shifted 180 degrees. What was once the fringe is now the inner ring. People openly refer to themselves as nerds all the time, guys and girls alike. There are tech nerds, music nerds, theology nerds, etc. It is a form of humble-brag.

Not surprisingly, San Diego’s metamorphosis from convention into festival has been rapid. Just ten years ago it was minor blip on Hollywood’s radar, an event covered by Wizard Magazine only. Today, every news outlet sends a reporter or three. It represents pop culture Zion, a celebration of nerd ascendency, a highly commercialized version of Burning Man. It was only a matter of time until someone penned a column about all the religiosity on display. Cue NY Times movie critic A.O. Scott’s column this week:

Maybe now “nerd” is a global category, which means that Comic-Con represents a mainstream made up entirely of misfits. Or, to put it another way, what was once a body of esoteric lore is now a core curriculum, and what was once a despised cult is now a church universal and triumphant… since the word “fan” derives from “fanatic,” more than merely secular knowledge is at stake. Invocations of quasi-religious experience — Comic-Con as “sacred space,” plot points and character traits as “canon” — are commonplace at the panels. Unbelievers are not so much unwelcome as irrelevant. For a long weekend in July, this city a few hours down the freeway from Hollywood and Disneyland becomes a pilgrimage site for something like 130,000 worshipers. It’s both ordeal and ecstasy, and the secular observer is in no real position to judge. You arrive as an ethnographer, evolve into a participant observer and start to feel like a convert, an addict to what is surely the modern-day opiate of the masses.

What are the doctrines and canons of this faith? In some ways, they aren’t so mysterious. The Comic-Con pilgrims, with their homemade costumes and branded bags of merchandise, represent the fundamentalist wing of the ecumenical creed of fandom. Almost everyone in the world outside falls somewhere on the spectrum of observance. We go to movies, we watch television, we build things out of Lego…

In other eras and societies — the Great Depression, the Soviet Union — long lines signify scarcity or oppression. In the Bizarro World that is 21st-century America, it’s the opposite: Long lines are signs of abundance and hedonism.

But the richest paradox of Comic-Con, and the key to its mysterious allure, lies in its ability to feel both absolutely corporate and genuinely democratic. In Hall H, you are aware of the distance between fans and celebrities, but also of the symbiosis between them. The most beloved creators here are the ones who can most credibly represent themselves as fans. Filmmakers like Mr. Tarantino or J. J. Abrams, who has taken over the “Star Wars” franchise, enjoy a special, exalted status. They are high priests who emerged from the congregation, geeks who transformed themselves into gods. But everyone else is made in their image. Even as Comic-Con enforces the distance between the idols and their worshipers it also insists on their shared identity… The deeper mythology of Comic-Con is that fans and creators are joined in communion, sharing in the holy work of imagination…

The world of popular culture only gets bigger, and as it does it grows more diverse, more inclusive and more confounding. It’s possible to imagine that someday everyone who has a badge at Comic-Con will also have a booth and a speaking slot on a panel, that fan and creator will achieve a singularity like the one predicted for human and machine. It’s almost possible to believe that we’re already there, that people are waiting in line for a chance to see themselves, even if they don’t always recognize the image.

Which line is the right one? Will I like what I find at the end? Why am I here, anyway? You may come to worship, but you stick around to question and to judge. I started out saying that Comic-Con is no place for a critic, but maybe I was fooled by the costumes, and everyone I saw was really a critic in disguise.

Pretty interesting. Contrary to the myth of the non-jugdmental outcast-with-a-heart-of-gold, it would appear that nerd culture has embraced the same power dynamics that traumatized it. Radical acceptance and common worship gets you in the door, but once you’re in, hierarchies form. Fiercely held opinions proliferate, factions develop (over the adaptation of a beloved property, etc), identity politics reassert themselves, and soon, whatever humility may have been present goes the way of Spock, post-Khan. (Michael Sansbury posted about the Pharisaism inherent in the system last year to great effect.)

If it sounds a bit like contemporary American Christianity, perhaps that’s no coincidence. I’m reminded of a mean-spirited but perceptive standup bit someone forwarded me the other day, drawing the parallels between religious know-it-all-ism and its pop culture expression (oddly enough, Pentecostals are a fairly mild version of what he’s talking about):

If you’re picking up on some personal investment, you’re not mistaken. I speak as someone with boxes of bagged-and-boarded comics in storage–someone with ‘nerd interests’ who spent an inordinate amount of time and energy during adolescence making sure the label didn’t fall on him. So I guess I feel a little betrayed. Stuff that once seemed so important turned out not to be. That thing I thought was ‘mine’ has been made generic. Comic books were a lot more fun when they were embarrassing.

Plus, whatever identity component non-nerdy nerds could lay claim to has been stripped away. You can’t claim that no one understands your love of 90s superheroes when everyone in the world is lining up to watch them. Now everyone knows who Ant-man is. There’s nothing special about a superhero movie premiere any more–and hasn’t been for a while. In fact, divested of its cache, what we thought was so special has turned out to be pretty pedestrian. Even with Paul Rudd as the main character (and co-screenwriter!). In other words, the second that “nerd” became a badge of honor, it lost its justifying potency. On to the next source…

Perhaps this is always happens when the minority becomes the majority. When a flipflop of power occurs, and the outsiders become the insiders. Meet the new boss, same as the old boss.

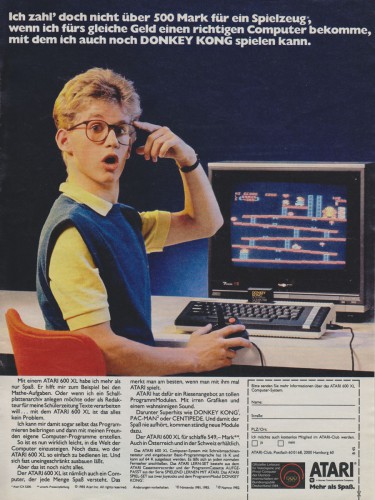

Whatever the case, it was in my mind last night as I watched the documentary, Atari: Game Over, which tells a pretty wonderful story of nerd redemption. The doc covers the time when nerds were truly nerds, the golden age of Atari, AKA the fastest-growing company in American history.

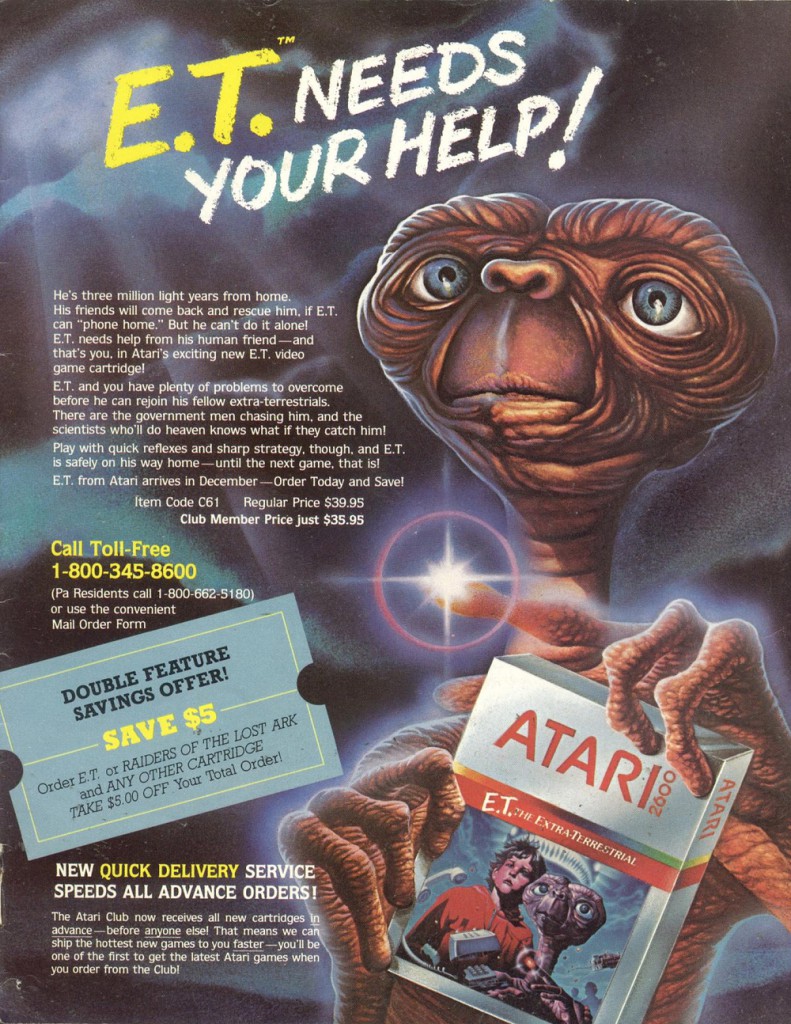

I was too young at the time to remember, but Atari flared out quite dramatically in 1983. Legend has it that the entire home gaming industry ground to halt following the release of “the worst video game ever”, E.T.: The Extraterrestial. The implosion was so swift that Atari apparently dumped millions of copies of the game in a landfill in New Mexico, just before being sold off by its parent company.

The film is a bit of a hodge-podge to be honest. But the best part, by far, involves Howard Scott Warshaw, the designer of the game in question, who refers to himself at one point as the guy “single-handedly responsible for toppling a billion dollar industry”. Quite a mantle to wear. Backstory is this: Capshaw was on a hot streak at the time, having recently designed Yar’s Revenge and Raiders of the Lost Ark, both million-unit-selling hits. Which is perhaps what made him foolish enough–or arrogant/nerdy enough–to accept the task of cramming a six month process into five weeks in order to get the cartridge ready for a Christmas release in 1982. Spielberg himself signed off on it.

Warshaw lost his job when Atari was eventually dismantled, and was understandably crushed–both by the demise of his dream company and his perceived complicity in said demise. We later find out that Warshaw left engineering thereafter to pursue a career as a psychotherapist with an emphasis on helping his fellow Silicon Valley engineers. In other words, his newfound “ministry” to his former colleagues/industry flows directly from his woundedness. Defeat gives birth to compassion and a desire to serve. Even Warshaw’s fluency in “nerd-speak” is redeemed. Go figure.

But that’s not the end of the film. The climax takes place in Alamagordo, NM, where the doomed inventory was supposedly buried (Matt 13:44). The filmmakers somehow convince the environmental authorities to allow them to excavate the landfill and solve the mystery of the dumped games. Warshaw is invited to attend and watches as his most notorious failure is literally unearthed.

But that’s not the end of the film. The climax takes place in Alamagordo, NM, where the doomed inventory was supposedly buried (Matt 13:44). The filmmakers somehow convince the environmental authorities to allow them to excavate the landfill and solve the mystery of the dumped games. Warshaw is invited to attend and watches as his most notorious failure is literally unearthed.

And yet, instead of shame, there is a crowd of onlookers there to applaud the find. Nerds of Warshaw’s generation (and a bit younger) had gotten word of the dig and flocked to the site. To them, the E.T. game represents something both precious and lost: their childhood. No one is debating or forming lines. A guy finds a broken joystick on the way to the bathroom and everyone gets teary. Shared weakness (and hope) is the basis of genuine fellowship. It couldn’t be further from San Diego.

Needless to say, Warshaw is moved beyond words. The stigma he has carried is somehow healed. But not through a display of power. Instead, what looked like failure–what was failure–provides the touchpoint for an enormous outpouring of catharsis and love. The worst thing has become the best thing. Game over.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NW6OP4ccsNk

P.S. Many thanks to Brian Solum for his help with this.

COMMENTS

5 responses to “Nerd Alert! The Curious Rehabilitation of Geeks”

Leave a Reply

Great stuff, David!

Scott’s article on Comic-Con reminds me of James K.A. Smith’s ‘Desiring the Kingdom,’ in which Smith uses the secular liturgies encountered in a pilgrimage through a suburban shopping mall to reveal the sacred nature of consumerism in America. It seems like the ascendency of nerd culture into the mainstream is perhaps akin to the explosive growth of a new denomination in said national religion.

Additionally, the comparison of comic book fanaticism and religious fundamentalism is poignant. I have been going to local comic shops for years, and the legalism I find in most of them is on par with the worst kind of churches. I’d rather say that I enjoy reading the apocrypha in a fundamentalist church than say I enjoy reading Geoff Johns’ ‘Justice League’ in a comic shop.

On this note, this article is apposite, specificially:

“”To my mind, this embracing of what were unambiguously children’s characters at their mid-20th century inception seems to indicate a retreat from the admittedly overwhelming complexities of modern existence,”

“”It looks to me very much like a significant section of the public, having given up on attempting to understand the reality they are actually living in, have instead reasoned that they might at least be able to comprehend the sprawling, meaningless, but at-least-still-finite ‘universes’ presented by DC or Marvel Comics. “

Amazing quotes, C. Thanks. Which article are they from? Last year’s (incredible) Alan Moore interview?