Tarantino’s Basterds is the ultimate anti-violence porn violence porn. Trouble is, it failed. Nazis, of course, are the archetypal modern movie villains, the evil “out there” which should be eradicated according to all of our moral judgments. For Internet nerds, Godwin’s Law expresses the sentiment perfectly: “As an online discussion grows longer, the probability of a comparison involving Nazis or Hitler approaches 1.” That is, the easiest way to vilify an opponent is to liken them to the Nazis.

Tarantino’s Basterds is the ultimate anti-violence porn violence porn. Trouble is, it failed. Nazis, of course, are the archetypal modern movie villains, the evil “out there” which should be eradicated according to all of our moral judgments. For Internet nerds, Godwin’s Law expresses the sentiment perfectly: “As an online discussion grows longer, the probability of a comparison involving Nazis or Hitler approaches 1.” That is, the easiest way to vilify an opponent is to liken them to the Nazis.

But the defining element of Nazism, as Eric Voegelin and others pointed out, is a Gnostic distinction between self and others that seeks purity by eliminating the other. In our demands for justice on an evil other, we actually judge ourselves – justice is comprehensive. Nazi-esque desire for purity achieved through vilification motivates our need for justice, so the Nazis are, by some strange logic, the perfect ‘villains’ to stand-in for viewers in a film condemning justice porn. The movie invites us to be judges, and then, in the critical theater scene, judges us and equates us with the movie’s villains, as Bryan J. pointed out in a fantastic post following the film’s release.

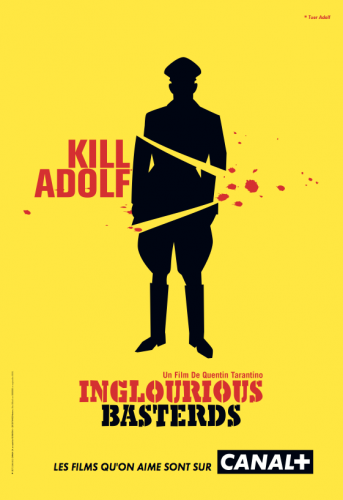

The film’s central symbol is the mark of Cain. Just as Cain was marked as a murderer after killing his brother, the carved swastika on the forehead etches cosmic, lifelong guilt into the Nazis’ very flesh. Brad Pitt’s character wants to mark others as villains, creating an easily identifiable us-vs-them symbol that is not, incidentally, too far removed from similar permanent markings the Nazis made on their enemies (which itself draws from the Mark of Cain tradition in literature and popular imagination – the symbolic tapestry here really is pretty incestuous).

But of course, Voegelin wasn’t the only one to realize that an us-vs-them mentality is characteristic of totalitarian regimes. He was doing his analysis from the Nazi German side, but Solzhenitsyn was busy at work on the Soviet side of things. Among his observations was the incisive one-liner,

“If only it were all so simple! If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being. And who is willing to destroy a piece of his own heart?” (Gulag Archipelago)

Well, Tarantino is willing to – in this movie at least. He flirts with the moralist’s wish in the first part of the movie, but in the movie screening he exposes the dark side of his heart, our hearts. He loves making violent movies, but he isn’t below critiquing them. After we’ve been loving this whole “kill the Nazis” thing for 60-odd minutes, we see the Nazis gleefully watching a senselessly violent movie featuring a sniper and a huge body count (paralleling us, for the last sixty minutes – in condemning them, we suddenly condemn ourselves), and the the screen burns up (fourth wall literally broken) as violence breaks out which, if we have a shred of self-awareness, we can no longer condone.

But the shred of awareness thing is a stretch. Never thought I’d say it, but maybe Tarantino’s anthropology is too high here – doesn’t seem like the theme really came across, because we really, really don’t like self-condemnation. Even if people got the fact that viewers bear the mark of Cain too, they got it mainly on subsequent reflection, so it was more an intellectual idea than the sort of emotional impact which good films are in the business of providing.

In the movie’s closing shot, of course, we see Pitt with the knife looking down at us – the camera is in the position of Nazi villain, we are the ones who, in the act of viewing and enjoying justice, have just received the Mark of Cain, the Mulvian gaze of moral judgment has been transferred onto us, etc, etc. So the movie invites us into a violent justice-fantasy, only to condemn us for joining the party. Next post, we’ll look at Django, which, unless I’m missing something huge, is regressive in depth and perhaps perpetrates the us-vs-them mentality that has been the foundation of all evil acts which Tarantino’s characters bumblingly attempt to rectify.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_detailpage&v=evDOp8HzGfY&w=600]

COMMENTS

3 responses to “Cain vs Cain vs Cain: Tarantino’s Moral Universe, Part 1 of 2”

Leave a Reply

Never thought of this, but it’s true. Another interesting fact is the bar scene: the audience is drawn to feel sympathy for Stiglitz, the serial killer ex-German army Basterd, and yet never (at least for me) feel an ounce of pity for the drunk private who just wanted to celebrate his new baby boy.

We give pass to a murderer and scorn a new daddy because of their uniforms. Dualism!!

Nice post, Will! I didn’t like Inglorious Basterds when I saw it (and I haven’t seen it since), but I may need to watch it just one more time to re-evaluate, because you brought out several concepts that I just totally missed. Even if Tarantino didn’t quite follow through as well as he could have.

I will be interested to see your Django post, because I actually found that film to be among Tarantino’s best films, but I am open to having my love of it challenged.

Thanks for this post.